Wash your smalls, feed the cactus, telephone your uncle Fred.

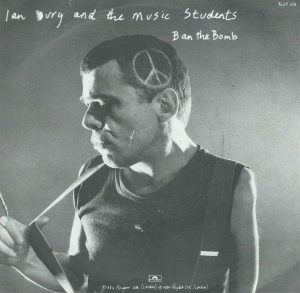

By the time this record’s finished everybody will be dead. — Ian Dury, ‘Ban the Bomb’ (1984)

they’ve got a bomb / they’ve got a bomb / they can’t wait to use it on me / they can’t wait to use it on you. — Crass, ‘They’ve got a bomb’ (1979)

As a small response to the frankly chilling nuclear rhetoric and military aggression coming from the Russian Presidency currently here are some links to open access (free) research I’ve done over the decades on:

As a small response to the frankly chilling nuclear rhetoric and military aggression coming from the Russian Presidency currently here are some links to open access (free) research I’ve done over the decades on:

- peace and music

- anti-nuclear and anti-war protest cultures,

for anyone who wants to find out more. The blog starts with my two most recent publications, which are kind of companion pieces where I explore different aspects (pop/post-punk, anarchist/grassroots) of music and peace protest related to the punk movement. These came from research and thinking related to large editorial project of The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock. Who knew they were still going to be quite so relevant.

‘Rethinking the cultural politics of punk: anti-nuclear and anti-war (post-)punk popular music in 1980s Britain.’ In G. McKay and G. Arnold, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock (2022)

This chapter is a reconsideration of the contribution punk rock made to anti-nuclear and anti-war expression and campaigning in the 1980s in Britain. Much has been written about the avant-garde, underground, independent, DIY and grassroots (counter)cultural politics of punk and post-punk, but the argument here is that such scholarship has often been at the expense of considering the music’s hit and even chart-topping singles. The chapter has three aims: first, to trace the relations between punk and cultures of war and peace; second, to reframe punk’s protest within a mainstream pop music context via analysis of its anti-war hit singles in two key years, 1980 and 1984; third, more broadly, to further our understanding of (musical) cultures of peace. Punk was a pop phenomenon, but so was political punk: the vast majority of the many pop hit songs and headline acts with anti-war and anti-nuclear messages in the military dread years of the early 1980s were a lot, or a bit, punky. This chapter argues that a wider and at the time significantly higher profile social resonance of punk has been overlooked in the subsequent critical narratives. In doing so it seeks to revise punk history, and retheorise punk’s social contribution, as a remarkable music of truly popular protest.

‘They’ve got a bomb’: sounding anti-nuclearism in the anarcho-punk movement in Britain, 1978-84. 2019. Rock Music Studies 6(2): 1-20.

This article explores the links and tensions in Britain between a musical subculture at its height of creative energy – anarcho-punk – and the anti-nuclear movement, including the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. It identifies and interrogates the anti-nuclear elements of anarcho-punk, looking at its leading band, Crass. At the centre is an exploration of the sounds of Crass’ music and singing voices – termed Crassonics – in the context of anti-nuclearism: if the bomb changed music and art (as Crass’s Penny Rimbaud brilliantly claimed), what did the new music sound like?

‘The pose … is a stance’: popular music and the cultural politics of festival in 1950s Britain. In G. McKay, ed. 2015. The Pop Festival: History, Music, Media, Culture. Bloomsbury, 13-31.

The aim of this chapter is to contribute to our understanding of the relation between popular music, festival and activism by focusing on a neglected but important area in festival history in Britain, what can arguably be seen as its originary decade, the 1950s. So I chart and interrogate the 1950s in Britain. I foreground the shifting cultures of the street, of public space, of this extraordinary period, when urgent and compelling questions of youth, race, colonialism and independence, migration, affluence, were being posed to the accompaniment of new soundtracks, and new forms of dress and dance. Includes Sidmouth Folk Festival 1955, Beaulieu Jazz Festival 1956, Aldermaston CND March 1958, St Pancras Caribbean Fayre (precursor of Notting Hill Carnival) 1959.

‘A soundtrack to the insurrection’: street music, marching bands and popular protest. 2007. Parallax 13(1).

What happens in social movements when people actually move, how does the mobile moment of activism contribute to mobilisation? Are they marching or dancing? How is the space of action, the street itself, altered, re-sounded? The employment of street music in the very specific context of political protest remains a curiously under-researched aspect of cultural politics in social movements…. By looking at the marching bands of different socio- political and cultural contexts, primarily British, I aim to further current understanding of the idea and history of street music itself, as well as explore questions of the construction or repositioning of urban space via music’how the sound of music can alter spaces’; participation, pleasure and the political body; subculture and identity.

‘Just a closer walk with thee’: New Orleans-style jazz and CND in 1950s Britain. 2003. Popular Music

This article looks at a particular moment in the relation between popular music and social protest, focusing on the traditional (trad) jazz scene of the 1950s in Britain. The research has a number of aims. One is to reconsider a cultural form dismissed, even despised by critics. Another is to contribute to the political project of cultural studies, via the uncomplicated strategy of focusing on music that accompanies political activism. Here the article employs material from a number of personal interviews with activists, musicians, fans from the time, focusing on the political development of the New Orleans-style parade band in Britain, which is presented as a leftist marching music of the streets. The article also seeks to shift the balance slightly in the study of a social movement organisation (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, CND), from considering it in terms of its ‘official’ history towards its cultural contribution, even innovation.

Subcultural and social innovations in CND. 2004. Peace Review: Journal of Social Justice 16(4), 429-438.

In times of war and rumours of peace, when ‘terrorism’ and ‘torture’ are being revisited and redefined, one of the things some of us should be doing is talking and writing about cultures of peace. In what follows, I ask questions about the place of culture in protest by considering the cluster of issues around CND from its founding in London in 1958. I look at instances of (sub)cultural innovation within the social and political spaces CND helped make available during its two high periods of activity and membership: the 1950s (campaigning against the hydrogen bomb) and the 1980s (campaigning against U.S.-controlled cruise missiles). What particularly interests me here is tracing the reticence and tensions within CND to the (sub)cultural practices with which it had varying degrees of involvement or complicity. It is not my wish to argue in any way that there was a kind of dead hand of CND stifling cultural innovation from within; rather I want to tease out ambivalences in some of its responses to the intriguing and energetic cultural practices it helped birth. CND was founded at a significant moment for emerging political cultures. Its energies and strategies contributed to the rise of the New Left, to new postcolonial identities and negotiations in Britain, and to the Anti-Apartheid Movement. In what ways did it attempt to police the ‘outlaw emotions’ it helped to release?

Chapter 6 of G. McKay, Glastonbury: A Very English Fair (Gollancz, 2000). ‘The politics of peace and ecology at the festival.’

The main political focus for funds at Glastonbury [Festival] started as the peace movement, and later embraced environmental campaigning more widely. In this context, the long-term relationships have been with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (1981-1990), Greenpeace (1992 onwards), and Oxfam (because of its campaigning against the arms trade), as well as the establishment of the Green Fields as a regular and expanding eco- feature of the festival (from 1984 on). T[his chapter explores how t]he radical peace movement and the rise of the greens in Britain are interwoven at Glastonbury.