Some (up to 2023) publications about punk in which I have contributions. Others are forthcoming or planned … well, especially The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock, which was a LOT of editorial work, and included a new chapter written by me as well. I am a little surprised by my own return in the past 6-8 years to looking at this decades-old moment, movement, or scene, tbh.

After OH Punk the book appears maybe I will have made my peace with punk. Actually that’s strictly not the case. I thought it would be. But I was asked to write an article for a new journal called DIY, Alternative Cultures & Society, and that piece (abstract below) is now completed, peer reviewed, and published.

I still haven’t made that entire memoir (OR Boy) available, have I (see bottom)? That was itself written at least 25, maybe 30 years ago. But even so, returning to punk so much over the past decade in a real unexpected flowering of scholarship, and so late (as it feels to me … 40+ years on, after all), I guess I must say that punk rock mattered to me, no, what I mean is matters to me, even. Weird? How much longer…? FFS.

Was punk DIY? Is DIY punk? Interrogating the DIY/punk nexus, with particular reference to the early UK punk scene, c. 1976-1984

This article [in the journal DIY, Alternative Cultures & Society] offers a critical provocation and reconceptualisation of the DIY/punk nexus, both to challenge the standard critical narrative of punk as originary DIY culture and to liberate the broader practice of DIY from the limits of punk.

It critically traces the development of the discourse of DIY both in original British punk c. 1976–1984 and in what has become punk studies, mapping the development of the scholarly orthodoxy.

It then challenges the latter via an interrogation of aspects of punk that have been repeatedly presented in the scholarship as evidence of its DIY-ness: punk mediation, instrumentation, and participation.

These three then constitute a context for the central and more detailed critical exploration of the most widely accepted DIY/punk practice, the independent or self-produced record, which is also read as ‘non-DIY.’

The article concludes by widening the critical gaze via a call for DIY to undergo a process of depunking.

Rethinking the cultural politics of punk: anti-nuclear and anti-war (post-)punk popular music in 1980s Britain

This chapter [in McKay and Arnold eds., The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock, 2023] is a reconsideration of the contribution punk rock made to anti-nuclear and anti-war expression and campaigning in the 1980s in Britain. Much has been written about the avant-garde, underground, independent, DIY and grassroots (counter)cultural politics of punk and post-punk, but the argument here is that such scholarship has often been at the expense of considering the music’s hit and even chart-topping singles.

The chapter has three aims: first, to trace the relations between punk and cultures of war and peace; second, to reframe punk’s protest within a mainstream pop music context via analysis of its anti-war hit singles in two key years, 1980 and 1984; third, more broadly, to further our understanding of (musical) cultures of peace.

Punk was a pop phenomenon, but so was political punk: the vast majority of the many pop hit songs and headline acts with anti-war and anti-nuclear messages in the military dread years of the early 1980s were a lot, or a bit, punky. This chapter argues that a wider and at the time significantly higher profile social resonance of punk has been overlooked in the subsequent critical narratives. In doing so it seeks to revise punk history, and retheorise punk’s social contribution, as a remarkable music of truly popular protest.

‘”They’ve got a bomb”: anti-nuclearism in the anarcho-punk movement in Britain, 1978-84’

[article published in Rock Music Studies 6(3): 217-236. DOI 10.1080/19401159.2019.1673076]

Who can say how much [the Bomb] changed all of us,… our music,… our art…? — Crass (‘Nagasaki nightmare’ sleeve notes)

This article explores the energetic links, contradictions and tensions in Britain between a musical subculture at its height of innovation and creative energy—anarcho-punk from around 1978 to 1984—and the anti-nuclear movement, including the social movement organization the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), during these same years when CND was at the second peak of its national and international prominence (its first having been in the late 1950s and early 1960s).

It identifies and interrogates the anti-nuclear elements of the musical package of anarcho-punk, looking at its leading band, Crass. Anarcho-punk was notable by its insistent political focus on war and the threat of nuclear destruction, and it presented a relentless cultural critique that drew on apocalyptic realities and drew post-apocalyptic imaginaries.

The article offers a critical discussion of the often rich lyrical, visual, and performative texts Crass made, and explores key ways in which anarcho-punk also interrogated links between the nuclear and music industries. At the article’s centre is an exploration of the neglected question of the sounds of Crass’s music and singing voice—my term is Crassonics—in the very specific context of anti-nuclearism: if the bomb changed music and art, what did the new music (of protest) sound like, in their portfolio? (How) could trying to articulate the inexpressible (nuclear horror) and express an adequate outrage at its possibility even produce a listenable popular music?

Click on this link for a FREE open access PDF: They ve got a bomb article Rock Music Studies 2019

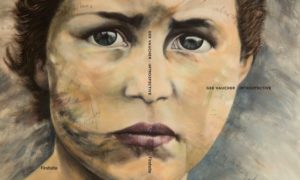

Gee Vaucher’s punk art as record sleeves

Gee Vaucher’s punk art as record sleeves

[catalogue essay, to accompany Crass artist Gee Vaucher’s major exhibition, Introspective, at Firstsite Gallery, Colchester, Nov 2016-Feb 2017]

Click on this link for a FREE open access PDF of my chapter in the catalogue:

mckay-catalogue-essay-gee-vauchers-punk-painting-as-record-sleeves

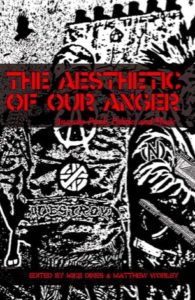

4WORD: AN.OK4U2@32+621984

4WORD: AN.OK4U2@32+621984

[foreword to the 2016 collection on anarcho-punk, Mike Dines and Matt Worley, eds. The Aesthetic of Our Anger]

Click on this link for a FREE open access PDF of my foreword for the book:

mckay-4word-the-aesthetic-of-our-anger

Punk rock and disability: Cripping subculture

[chapter in Blake Howe et al, eds. 2015. The Oxford Handbook of Music and Disability Studies. Oxford: Oxford UP]

This essay is focused on (post)subculture and disability and specifically on punk rock. It aims to extend our understanding both of punk itself and of subcultural theory, adding to ideas around postsubculture by cripping it, that is, by identifying the sounds and styles and bodies of the disabled, who are the neglected already-present of punk, and whose presence disrupts subculture theory, even while such theory exists in large part to understand the disruptive potential of gesture, music, youth, fashion, attitude, and modes of walking and talking. Here I concur with, and seek to develop, the observation by David Church that “disability has been one of the most foundational—and yet, one of the least explored—representational tropes of the punk milieu”.

The essay contains two main areas: an initial discussion of subculture and counterculture in terms of theory and of disability and a focus on the original British punk scene of the late 1970s and three major artists, varyingly disabled, from it: Ian Dury, Johnny Rotten, Ian Curtis. It concludes with a view of punk’s “cultural legacy” in the disability arts movement….

Complete FREE open access text of chapter available by clicking title above.

OR Boy: A Norfolk Punk Spills the Beans

… there is just one thing I should like to say, about those monuments they have erected to the men that fell in cruell and greedy war. They have put on them ‘For God and Cuntry’. The People think wen they read them words that a good God ment that his human beins should be murdered for the lust of Nations, and there greed…. Now they talk about disrament, yet still the cuntrys go on making killing mashiens for the purpose of murdring there fellow men. It may be that I do not hold with monuments.—I Walked by Night

Have you ever read I Walked By Night; Being the Life & History of the King of the Norfolk Poachers, written by ‘himself’, edited by Lilias Rider Haggard? It was first published in 1935, and consists of the anonymous autobiography of an English country boy written in his old age, looking back on his life through the later nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth. It is probably the most famous of the East Anglian rural memoirs, due to the attractive power of the textual voice. The unorthodox writing style, spelling, and sometimes dialect language—I thought when I first read it in deepest north Norfolk in the frozen winter of 1984, fresh from my degree in Englit and hiding from my future, that it was touched with a minor modernist aesthetic.

Gaoled as a youngster in Norwich Castle for doing ‘a bit rong’—full of the old stories he’d heard about ‘the horrors of tranceportation’—the narrator remembers the unfairness of how ‘the Justice of the Piece’ and the ‘Maderstrates’ could ‘send a Boy to Prison for killing a rabbitt’. As he concludes of that episode: ‘I know that they soured me to the Laws of the Land’. (In a wonderful capture of how to write spoken Norfolk, he spells the word naked ‘naket’; a hawk is a ‘hork’.)

My copy of I Walked by Night, the 1948 ‘bound cheap edition’, is a hardback with a lightly embossed set of small animal footprints in a corner of the front cover, difficult to see.

In a short preface, the editor (daughter of the Victorian novelist H. Rider Haggard) offers a version of how the book came about: ‘It is entirely his own work, but it is not as it appears here, as it was in no way consecutive. It came to me on letters and on scraps of paper, in old exercise books, on anything that was at hand…. I have done but little pruning; most of my work has been arrangement of material so as to make the book a narrative, with the incidents in their right places’.

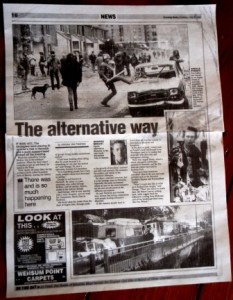

Well reader, I have been given what is in some ways a not dissimilar memoir, though it is one about the punk rock movement in Norwich and Norfolk in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and much shorter than I Walked By Night. Here is how the MS came to me. In 1996 I was doing some press publicity for my first book, Senseless Acts of Beauty, and in an interview with the  Eastern Daily Press or Evening News from Norwich, I happened to mention in passing that I might one day like to write more about radical East Anglia. In the newspaper article that became something like ‘His next project is a book called Radical East Anglia’, and a surprising number of people read that statement and got in contact with ideas and suggestions, and offers.

Eastern Daily Press or Evening News from Norwich, I happened to mention in passing that I might one day like to write more about radical East Anglia. In the newspaper article that became something like ‘His next project is a book called Radical East Anglia’, and a surprising number of people read that statement and got in contact with ideas and suggestions, and offers.

A scrappy collection of papers arrived, via someone who knew someone who knew me, with a cover sheet saying OR Boy (the title needs to be spoken aloud, the letters of the first word spelled out, to get the joke). At that stage I’d only written one book, but someone out there seemed to think I’d

be capable of editing their own messy memoir, shaping it into something slightly more coherent. I was flattered and curious, and, when I started reading, excited. Now I was walking by night!

In their youthful earnestness, or their overwritten stylelessness, or their attempt at mythic depth, or their effort to write the musical landscape of the countryside, these writings really appealed to me. I thought (still think) they should be published, but they were not, nor, to date, have been. I now have the agreement of the author to make them available here, on this website. On one condition: the author’s continued anonymity. The plan is to ‘publish’ one chapter at a time, in order, over the course of a year or so.

Are you ready? Are you interested? We’re starting soon. I mean, we are starting as soon as there is some interest …

George McKay in conversation with Penny Rimbaud, of Crass anarcho-punk collective, 2008

‘Germany got Baader-Meinhof, Britain got punk’—Crass, 1977. Discuss.

Film of Penny Rimbaud, key artist in the British anarcho-punk movement and prime mover behind the band Crass, in conversation with Professor George McKay, University of Salford. Society & Lifestyles: Subcultures & Lifestyles in Russia & East Central Europe conference. Organised by the University of Salford and the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), 4-6 12 2008 Old Fire Station, UNIVERSITY OF SALFORD.

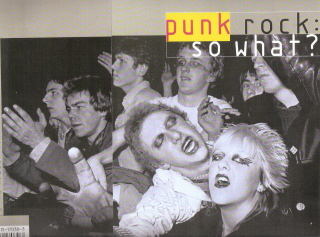

‘”I’m so bored with the USA”: the punk in cyberpunk’, essay in Roger Sabin, ed. Punk Rock: So What? The Cultural Legacy of Punk (London: Routledge, 1999), pp. 49-67

Then was America / We went there … /All the English groups act like peasants with free milk.—The Fall, ‘C’n’C S.mithering’

… There was something of an antagonistic relation between Britain and the United States in the punk side of popular culture, as seen in the song ‘I’m so bored with the USA’ by the Clash, a boredom which understandably lapsed when American stadium rock success and, later, Levi’s advertisements came along. Anarcho-punk band / collective Crass are typically more direct, concluding one song which presents American airbases, fast food and popular culture as facets of a cultural and military imperialism: ‘ET go home, Mickey Mouse fuck off’. There are more interesting narratives than these, though. Here’s the Fall again, with one of Mark E. Smith’s ‘crap raps’….

… There was something of an antagonistic relation between Britain and the United States in the punk side of popular culture, as seen in the song ‘I’m so bored with the USA’ by the Clash, a boredom which understandably lapsed when American stadium rock success and, later, Levi’s advertisements came along. Anarcho-punk band / collective Crass are typically more direct, concluding one song which presents American airbases, fast food and popular culture as facets of a cultural and military imperialism: ‘ET go home, Mickey Mouse fuck off’. There are more interesting narratives than these, though. Here’s the Fall again, with one of Mark E. Smith’s ‘crap raps’….

Review of John Lydon autobiography, ROTTEN, in Popular Music (1995, 14:2, 279-281)

Am I a walking contradiction?… Oh yes, I’m not. —Johnny Rotten

Read the review ….

One reply on “Punk”

Ended up here by chance and enjoyed your post. Will take the time to read more soon.