Some of the counterpanes are pink, and some of them are blue.—Ian Dury, ‘Hey, hey, take me away’ (1980)

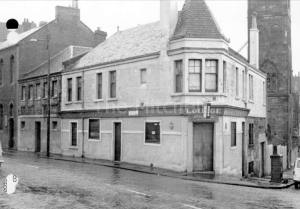

My autopathography, in 1300 words. I was born in Glasgow at the start of the ’60s, at home in the kitchen of our Cowcaddens flat, in fact, above a pub, the Park Bar. My mother’s family were Cowcaddens folk going back generations.

Mearnskirk Hospital

As a wee boy in Scotland, I was in hospital for muscle-stretching treatment on my lower limbs, including a period in a residential children’s hospital outside Glasgow called Mearnskirk. This was because I had poor balance and seemed to walk permanently on my toes. Here I stayed in the polio ward, where my bed was at the far end of a long thin ward near the windows, past the other wee boys lying in their iron lungs to aid breathing. I found them (the life-giving machines) quite frightening at first. There were lots of windows that opened straight out into the grounds so that, in good weather, children could be wheeled outside in their beds if need be for the simple therapy of fresh Scottish air. (Mearnskirk had previously been a tuberculosis hospital.) There was a Peter Pan statue in the garden.

My mother used to drive out from the city and see me every day. My father actually bought me a present, and I’m told it was the first time he’d done that unprompted. I saw Celtic winning the 1967 European Cup on television in there (sometimes I wonder if it was the semi-final). I remember I was sent home in full leg plaster casts for months too afterwards in the hope that my muscles would stretch and I would be able to walk normally. An experimental surgical intervention was suggested but my mum said no.

I found these ‘ditties’ the children used to sing, from ‘Memories of a young patient‘, a short piece of writing of a boy’s experience there in the 1950s, from three (three!) to eight years of age. (I wonder what the melodies were.)

Ham and Eggs, you’ll never see / Dirty water for your tea, / How would you like to come with me, / To Mearnskirk?

and

I’m tired of Mearnskirk and I want to go home / It’s weeks and weeks and months and months / Since I saw ma home / Mammy, daddy, take me home.

Cowcaddens and beyond

When I did get home, the Cowcaddens was almost entirely demolished in the name of the city council’s programme of slum clearances in the 1960s (well, and to make way for the wound of modernity that was and is Glasgow’s urban motorway, the M8). Community clearances. My family were moved to a council flat in one of the brand new tower blocks in Maryhill. Most of our wider family were displaced from the Cowcaddens to one of the new council schemes on the edge of the city, Easterhouse. This would become a notorious social experiment, I don’t know if that’s too strong.

Having our entire historic city centre community—family, friends, schools—shattered, we took the hint, and joined the Scottish diaspora by moving to … England. We lived in caravans and railway cottages in Norfolk (if that sounds idyllic, it … wasn’t). At aged 13-14, I had follow-up tests at Addenbrooke’s in Cambridge and the Jenny Lind Children’s Hospital in Norwich. I strongly remember being forbidden to wear platform shoes (this was the early 1970s. Crushed).

Curiously, I was never really definitively diagnosed at age 5-6 or 13-14. (In the early 2000s my Aberdonian consultant Prof Mitchell was most puzzled that I’d never been given nerve conduction tests as a child or youth in Scotland or England. In 2020 the team of my consultant Prof Reilly at the National Hospital for Neurology finally located those old medical records and it turns out I had undergone nerve conduction tests as a youngster.) A couple of years later, mid-late 1970s, after the platforms incident and as a punk rocker, it was actually quite an asset to have an unusual gait.

Then I was 40

Then I was 40

Then I was 40, tripping up a lot (every day), finding myself having real difficulties doing my wriggling children’s buttons up. My handwriting—never an asset or thing of beauty—seemed less legible to my students, though I could usually still read it. Chatting to one of them after a class, a quite visibly disabled guy in his 30s (something neurological and terminal, he told us calmly), I was completely floored by him asking me what I had. I really panicked after that seminar, and couldn’t get out of my mind the look of puzzlement on his face. He knew more about me than I did.

A while later I actually realised my lower limbs didn’t seem to be doing what I expected any longer, nor could I even lift my feet. I decided that if I tripped and fell over more than once in a single day I would do something about. Sure enough, pretty soon I did. I’ve always been a spectacular faller. So I saw my GP, who examined the palms of my hands and fingers as well, and asked how long they had been like that. In an absurd confirmation of the masculine lack of self-knowledge of one’s own body, I actually did reply ‘Like what?’ to that question. I saw the blood rise up his neck and face.

CMT

Off to the neuromuscular consultant, and a set of nerve conduction and other tests. Anyway, muscular dystrophy it used to be categorised as. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease is my condition’s exotic and historic name (yes, that Charcot). Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (attenuated muscularity of lower legs and hands/forearms); I’m a classic case. It’s an incurable progressive muscle-wasting condition, which I tend not often to describe it as, since that can be a bit of a downer in convo.

But let’s not overstate it: there are worse and nastier conditions in the neurosphere, and mine, my CMT, isn’t life-threatening. Something like 23,000 people in the UK have it. Only aged 60 thanks to extensive genetic testing at the wonderful National Hospital for Neurology was my diagnosis definitively pinpointed to CMT Type 1a, the most common type. Certainty of balance, the ability to stand, walking unaided, physical strength, dexterity and fine motor movement, the sense of feeling and distinction, all have diminished and are diminishing.

‘Anything that rhymes with me‘

Around the time of my initial diagnosis—it’s fair to say, yes, that my turn from 30 to 40 was a bit of a personal crisis period—I was at Glastonbury Festival in June 2000, publicising my latest book. I noticed that Ian Dury & the Blockheads were due to play, and went off to see them. I’d seen that very band many times in the past, including in 1977 on the Stiffs package tour, with Wreckless Eric and Elvis Costello, and when Wilko Johnson of Dr Feelgood became a Blockhead in 1981 too. I didn’t realise why I wanted to renew the acquaintance, beyond that I thought it might be fun. Alas Dury wasn’t able to play at Glastonbury that day, being too ill with cancer.

But Dury, the disabled punk-era singer, was in my head again, that ‘raspberry ripple’, that ‘flaw of the jungle’, and just when I needed him. How considerate and generous. I began to think about the disabled body in pop and rock, and read around on it. Fortunately there wasn’t at that time that much to read—an excellent situation for a writer looking for a topic or a diversion, seeking some ‘knowledge of selfhood and body-truth’, as Petra Kuppers has nicely put it….

The journey to that knowledge for me started in the Glasgow polio ward in the 1960s and the punk rock scene of the 1970s. From it has come quite a lot of work on polio and pop, an AHRC research project called ‘Spasticus’ (after the Dury song, of course), a book called Shakin’ All Over, focused pieces of writing on punk and disability, on jazz and disability. Applied deconstruction, someone said.

(Sub-heading quotation is from Kevin Coyne, btw.)

4 replies on “Autopathography”

Hi Gary, thanks for getting in touch. There’s quite a lot about Robert Wyatt in Shakin’ All Over, both in terms of the voice and around his work exploring his experience. (Kevin Coyne too, for different reasons, but people still seem less interested in Coyne despite his powerful body of work.) I hope if you do read the book you’ll find plenty of material of interest in it. George

Hello George, I haven’t been able to get my hands on the book yet. Do you mention Robert Wyatt therein?

I enjoyed very much Circular Breathing, so I will definitely try and get hold of this.

best, Gary

Thank you so much for coming to the Freie GartenAkademie lecture in the wonderful allotments in Munster on Saturday. *And* through the rain! I had a lovely tour round some Munster gardens on Sunday morning with Wilm Weppelmann–the Occupy garden in ‘Occupy-Platz’ (thank you, Joshua), Wilm’s embryonic Hunger Garden project, the Ian Hamilton Finlay piece up a tree in the park, some guerrilla gardens too. I hope you enjoy Radical Gardening–do let me know. I want to return to the case of Humphry Repton, the 18th/19th century landscape garden designer, who had a serious accident late in life that disabled him, to explore the extent to which his physical disability (impaired mobility, wheelchair use) influenced his garden design, if at all.

saw you yesterday at the garden academy in münster. you don’t look disabled in any way, i just enjoyed your lecture and am going to buy your book. by the way, i am diagnosed with multiple sclerose and write to you to tell you that it is a personal pity to have a desease, but in the long end it doesn’t really matter. it makes people more concentrated, powerful and effective and me perhaps a bit more obstinate to do my things. greetings from rainy münster!