Colin Bailey

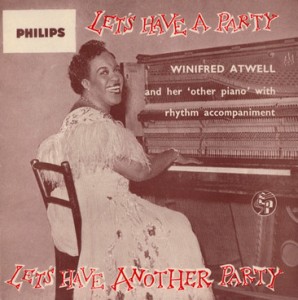

Drummer with pianist Winifred Atwell in the 1950s. I interviewed him because of some research I was doing on the Trinidadian honky-tonk hit parade pianist Atwell, who had 16 hit singles in the 1950s, and was the first black number one artist in the British charts. My key question, for Bailey as for the research, was concerned with why Atwell is still excluded from jazz histories. I have addressed this question in a 2014 chapter on Atwell in Jason Toynbee et al eds. Black British Jazz.

Bailey was born in Swindon in 1934. Now lives in California. In Australia in the early 1960s he was a member of the Australian Jazz Quartet. Became an American citizen in 1970. Playing, recording and touring nationally and internationally with Atwell in the early 1950s was a major early break in his music career. As he said to me more than once, ‘I wouldn’t be where I am if hadn’t been for Winnie’.

In his jazz, recording and performing career in the US, Bailey has worked with Frank Sinatra, Joe Pass (with whom he recorded 14 albums), Miles Davis (depping for the teenaged Tony Williams who was too young to get a club licence—‘one of the thrills of my life’), George Shearing, Benny Goodman, and many others. Also an experienced teacher, he is author of influential drum technique books, including the best-selling Bass Drum Control, has recently released the DVD Bass Drum Technique, and he is a former music lecturer at North Texas State University. His website on ‘the art of jazz drumming’ is at: http://colinbailey.com

In 1978 Bailey was flown out to Australia from the US as a special surprise guest for Atwell’s appearance on the Australian television version of This Is Your Life.

Telephone interview, May 6 2011, with corrections 13 June 2011

In July 1952 I was a young musician learning at Ivor Mairants’s Central School of Dance Music, in London. Ivor played guitar with Winnie on her recordings, and she was looking for a new drummer, so I auditioned, at his suggestion. There were two drummers, and I thought the other player was better than me, but they chose me. Later, Jan—my wife—was Winnie’s dresser, so it was a perfect arrangement, for touring and travelling. I wouldn’t have had the life, the international musical career I have had if it weren’t for Winnie.

I played on lots of the recordings, the hit singles—‘Britannia rag’ I used the sticks on the rims, I remember; I was on ‘Coronation rag’ too. When we’d recorded ‘Dixie boogie’ I do remember she complimented me on my playing. When we did recording sessions it would be Ivor on guitar, me on drums, and the best other musicians around for the rest of the rhythm section. In concert, on tour, it would be me on drums, mostly brushes. I played in the pit while she was on stage. She took me along to keep a clean time. I only ever took a snare drum with me, and would use the rest of the pit drum kit as I needed it. Actually all I ever used was a snare, a hi-hat and a cymbal, even on the recordings. There would be a bassist from the pit band or orchestra in whatever venue or city we were in—and some of them really were dreadful, because they couldn’t get the feel or the drive of her music, even though they had all the charts and could usually read well enough. So a lot of times live the bass was just a low percussive noise, an extra. Her left hand was pretty driving anyway.

On the records, no-one got a credit—only Winnie. Not even Ivor, who was a pretty well-known musician in his own right, of course.

On the records, no-one got a credit—only Winnie. Not even Ivor, who was a pretty well-known musician in his own right, of course.

Winnie didn’t improvise on the piano, she couldn’t improvise—she had a very good feel for boogie-woogie, and great swing, really powerful. Yes, she could swing and she had a great feel. But she couldn’t improvise and that’s why I think some people don’t want her in that list of proper jazz musicians that you’re thinking of. To that extent you can see why people say she’s not a jazzer. But we did do a lot of different material especially on those Australian tours, and some of it was from the jazz repertoire. But then again, when she did those concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London with the Philharmonic Orchestra—Grieg’s concerto—that took an awful lot of guts, and she had to practise like crazy to get up to it.

She wasn’t in the jazz scene in London in any way really.

Nobody ever said anything about her being black.

The thing with Winnie was—people loved her, everybody adored her. Houses were packed and audiences really warmed to her, and she was normal, no airs and graces, even when she was top of the charts. She had such a nice personality.

In 1955 we toured Australia and New Zealand, we were away for 15 months. The houses were packed everywhere. When we came back, in February 1956, I had to make a change, a musical change—I wanted to be in a dance band, and I suppose I was finding the music I played with Winnie too restricting. The money was great, and international travel, and Winnie and Lew [Levishon, her husband, and manager] always treated me right—but I thought I needed a change. Funnily enough Jan and I were going out to Australia in 1958 just when Winnie was doing another tour there, so we ended up working all together again.

David Rohoman

Drummer with Ian Dury’s first main band Kilburn and the High Roads in the early 1970s. Before that he was in the quite extraordinarily-named rock band Kripple Vision. I interviewed Rohoman—took me a long time to track him down, and he’d never responded to interview requests from either of Dury’s biographers—both because he’d worked in that influential early band, and indeed played on the recording of the one Kilburns album Handsome (1976), and because he is physically disabled himself. This was to contribute to my research for Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (University of Michigan Press, 2013), supported by the AHRC.

Drummer with Ian Dury’s first main band Kilburn and the High Roads in the early 1970s. Before that he was in the quite extraordinarily-named rock band Kripple Vision. I interviewed Rohoman—took me a long time to track him down, and he’d never responded to interview requests from either of Dury’s biographers—both because he’d worked in that influential early band, and indeed played on the recording of the one Kilburns album Handsome (1976), and because he is physically disabled himself. This was to contribute to my research for Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (University of Michigan Press, 2013), supported by the AHRC.

Interviewed in person, in a London restaurant, 14 September 2010. Today Rohoman is a London-based jazz drummer, and plays with the Vlad Miller Trio.

Autobiography, autopathography

…having something wrong with your leg doesn’t stop you playing your instrument

I was born in 1948, in British Guyana. I was, as I say, fortunate in my upbringing: my father was a major, my mother a beautician. We weren’t middle class, but we were comfortable, and we would have treats imported from America or England that I realised some of my friends didn’t have.

Because of my legs quite seriously not working properly, I was diagnosed at birth originally with hereditary spastic paraplegia. But in fact, they later found out that my disability was due to my mother eating cassava root that hadn’t been prepared properly when she was pregnant withn me. Cassava is high in cyanide if the skin isn’t washed properly, and that affected the foetus. That was quite a common thing in those days.

From the waist down my muscles were very, very tight, and by the age of 11 I had had thirty major operations to stretch them, and sort my hips out too. As a boy I could walk around, but with a noticeable gait. Everyone noticed me walking—but it didn’t bother me, I didn’t give a toss, just got on with things. I was clever too, a clever boy, and that probably helped me out.

I came to Britain with my mother. She had aspirations of me being a doctor. She said I was too intelligent to waste time or an opportunity. She came over to England, choosing it over America because she had a sister here. This was in 1951-52 probably, but she went back and forth quite a lot. Then she sent for us, and we arrived in 1962. I was 12 or 13; it was June; we settled at first in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire.

My medical operations continued in the UK. I remember one of the treatments they did was Faradayism on my legs: this was a series of electric shocks for muscle stimulation, and then you were submerged into a bath of warm wax, all intended to stimulate the muscles. I was advised by the physiotherapist I needed constant exercise. It was either a bicycle or a tricycle, or—since I was into music such a lot, I’d sing Everly Brothers songs, I liked the Shadows, that kind of thing, the new western pop (funnily I never liked, you know, Caribbean music really, reggae or calypso, didn’t appeal)—a physically demanding musical instrument. So: drums.

Playing the drums

Originally when I took up drums—a bass drum and a hi-hat was my first kit. Two pedals, so totally focused on the legs. I wanted to be a singer really, I’m a better singer than drummer, well, in my view. But I didn’t like being up front, didn’t like being the focus of attention. In fact, when he was forming the Blockheads, Ian Dury asked me to be a singer in the new band, not the drummer. But by then I was really drumming jazz rather than rock music, and I said no.

One time my mum had to go into hospital for an operation, and I was looked after by being sort of fostered in a home. The house master, Mr Hunt, brought me a pair of drumsticks. That was a good thing. I used to play on the books, practising rhythms all the time. There was a song in the charts at the time called ‘Wipeout’, with a strong rhythm and drums up front, and I’d play along to that all the time.

A friend had a function band. And one night they needed a drummer for a gig. They asked me, and I played: only five or six numbers, but it was my first gig, at the age of 16 or so. All the adulation, the applause—I liked it, seriously, I thought ‘This is where I belong’. After that, I practised and practised and practised, and I went out of my way to be as good as or better than most of the other guys around. In a way I suppose I had to, being a disabled drummer. There was this pop drummer, Sandy Nelson, who had one leg, and he had a hit single called ‘Let there be drums’. I went over and over that song learning to play it—I thought OK Sandy Nelson, I’ll show you what’s what. He was disabled, see, but well known, and I thought if I could be better than him I was proving something, about my own music and drumming.

If I wasn’t disabled I’d have been the singer, not the drummer!

That’s a buzz I get even now. I’m at a new venue setting the kit up, and during the warm-up I like to play something totally naff. People are watching, the musos in the audience clocking what I’m doing, wondering if that guy playing drums like that can be any good. ‘Oh he’s there on crutches, he’ll just be keeping time’. Then once the band starts playing I like to see their faces, all looking surprised as I’m cooking away, in control, in command.

I drum like no-one else does. [Laughs] I don’t mean that in a conceited way. I mean with my legs the way they are, and even the way I hold the sticks, I have to play like that and so I do. I do play to my strengths. So yes, as you’d put it, my life’s deficit has also supplied me with my life’s creative opportunity.

I can play the tune with my right hand, fills and accents with my left. With my legs: I can do fours on the hi-hat, and triplets on the bass drum. It’s true I can’t really sustain things, like playing the bass drum fast and for a long time.

I’ve got a muscle wastage on my hands, so I hold the sticks in an unorthodox manner. They don’t rest between thumb and finger, I haven’t got enough grip there and the sticks would just fly off. I hold them between the first and second fingers.

When I’m playing I try to play as differently from clichéd rhythm as I can. Most of the music I hear in my head the beat is on the other side. I hear it on the 1 and 3, not on the 2 and 4. And odd time signatures in jazz, I can just do them without really thinking or even consciously counting them.

When I’m playing I don’t think of myself as a disabled drummer. And I like to give the audience the reaction: ‘Ah here’s a guy on crutches, but he can really play’.

Why jazz? Jazz gives you the opportunity to paint pictures. It’s about how you feel at that time, and you play and develop the music by feeding off each other on the stand.

Kripple Vision and Ian Dury

KV was a quite successful rock band I was in in 1972-1973. We supported the Rolling Stones, toured around the country with other bands, played regularly at the Roundhouse in front of 2000 people, all that kind of thing. I was also in Heinz’s backing band, called the Magic Rock band—we supported Gene Vincent once. KV was a four-piece: drums, bass, lead guitar, vocal, the same line-up as Led Zeppelin. A lot of our stuff was original, and because the guitarist and bassist were Sinhalese, there were a lot of Eastern modes in the music. It was a bit like the Mahavishnu Orchestra with hard rock vocals! We used to go down a storm, really, the hippy audiences loved us.

At first we were called ‘Vision’, but we did a John Peel live radio broadcast one time, and our manager, Errol da Silva, realised the visual impact of the band was getting lost—not just because it was on the radio, but he thought the band’s name didn’t really catch our appeal either. ‘Vision’ wasn’t enough of a selling point, and Errol thought that I should be exploited, the fact of having a disabled drummer should be capitalised on. When we played live, I was centre-stage, just behind the singer, so when he was off waving his long hair around and doing his screams, it was me the audience were looking at. They’d have seen me walking across the stage on my crutches before the start of the gig, so knew I was different. And in smaller venues, I’d have to walk through the crowd to get to the stage, and again, the audience would remark on it: ‘That guy on crutches, he’s the fucking drummer!’, that sort of thing.

He was a very direct little man, Errol! And the name change was his idea. He said we should be called Cripple Vision, but to be honest, my mother wasn’t very happy with that at all. She didn’t like the idea of it, and how it reflected on me. So between them they reached a compromise: Kripple Vision. And we were called that because Errol thought it would be a good way of exploiting the disabled drummer in the band. I didn’t mind—I didn’t feel I was being exploited or anything, I thought completely the opposite: here I am making a creative living in the industry, and people love it. And even now: when you think about it, I’ve been drumming for a long time, it’s been my life.

Eventually I was sacked from the band, at a Monday rehearsal. It was fair enough really: I’d gone off the Paris for the weekend with a lady and the return flight was delayed. I missed a Sunday afternoon gig at the Roundhouse, and the band had had to play in front of a full crowd as a trio: Kripple Vision without the cripple. After I left they shortened the name to KV and carried on for another couple of years. Actually I was invited back into the band later, but by then I’d been doing more and more jazz and going back to rock wasn’t so appealing, it didn’t work, so I left.

After KV I was in a band on the same bill as Ian Dury one night, and he came over and said ‘I like your drumming … it reminds me of scrambled eggs’. This was because my arms were moving close round so much, like whisking. He invited me to join his band there and then—this was his early art school band, God they were terrible, I just said ‘No way, never’. A while later he was somehow round at my house, and my mum was cooking for him. Ian could be very charming, and before I knew it my mum was saying ‘Oh why won’t you join this nice young man’s new band David, you never know where it’ll lead’. So I was in Kilburn and the High Roads then.

Those successful years proved to me that if you have the determination, the drive, then you can achieve almost anything. Who dictates what the norm is? And being with Ian [Dury] in Kilburn and the High Roads, just made that feeling even stronger. That band was an intimidating and powerful collection of very unusual people, disabled, freakish, frightening I suppose for some of the audience. There was Ian at the front, me behind the drums, short little Charlie [Sinclair], great big tall Humphrey [Ocean], and on sax, yes, Davey Payne who you never quite knew what was going to happen with, always a bit of edge. [Laughs] No one else but Ian could have gotten that sort of bunch of musicians, those characters, to play together. It says a lot about his I suppose man management, not necessarily what you usually think of with Ian. He chose each person not only for their musical ability or inability, but as though he was making a painting, a mosaic. I think he’s done a lot for disabled people: he’s made ‘normal’ people realise that being short, or having something wrong with your leg, doesn’t stop you playing your instrument.

Those successful years proved to me that if you have the determination, the drive, then you can achieve almost anything. Who dictates what the norm is? And being with Ian [Dury] in Kilburn and the High Roads, just made that feeling even stronger. That band was an intimidating and powerful collection of very unusual people, disabled, freakish, frightening I suppose for some of the audience. There was Ian at the front, me behind the drums, short little Charlie [Sinclair], great big tall Humphrey [Ocean], and on sax, yes, Davey Payne who you never quite knew what was going to happen with, always a bit of edge. [Laughs] No one else but Ian could have gotten that sort of bunch of musicians, those characters, to play together. It says a lot about his I suppose man management, not necessarily what you usually think of with Ian. He chose each person not only for their musical ability or inability, but as though he was making a painting, a mosaic. I think he’s done a lot for disabled people: he’s made ‘normal’ people realise that being short, or having something wrong with your leg, doesn’t stop you playing your instrument.

Jazz in Britain: interviews with modern and contemporary jazz musicians, composers and improvisers (2002-03)

I undertook these interviews (click blue title above for the link) as part of the research project I was working on, Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain. The primary output of the project was a book of the same title. This was an extension into more recent music practice of the interviews I’d undertaken regarding the trad boom of the 1950s. Both sets of interviews were for research funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board, and I am grateful for the board’s support.

I undertook these interviews (click blue title above for the link) as part of the research project I was working on, Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain. The primary output of the project was a book of the same title. This was an extension into more recent music practice of the interviews I’d undertaken regarding the trad boom of the 1950s. Both sets of interviews were for research funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board, and I am grateful for the board’s support.

There is a slant towards discussions about cultural politics, in particular race, gender, and national identity, because that was the way the questions were phrased, those were the issues I was interested in exploring.

There is a slant towards discussions about cultural politics, in particular race, gender, and national identity, because that was the way the questions were phrased, those were the issues I was interested in exploring.

Interviewees (to whom, thank you):

• Eddie Prévost

• Mike Westbrook

• Keith Tippett

• Maggie Nicols

• Steve Beresford

• Kate Westbrook

• Tony Haynes

• Gary Crosby

• Ben Crow

• Deirdre Cartwright.

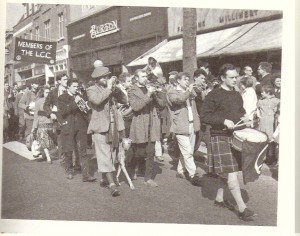

Trad jazz in 1950s Britain–protest, pleasure, politics–interviews with some of those involved (2001-02)

These are transcriptions of interviews and correspondence undertaken as part of an Arts and Humanities Research Board (now Council)-funded project exploring the cultures and politics of traditional jazz in Britain in the 1950s.

The project ran through 2001-2002 and was entitled American Pleasures, Anti-American Protest: 1950s Traditional Jazz in Britain.

I edited responses, and structured them here according to the main issues I asked about and to key points that seemed to recur from different interviewees. There is a short-ish introduction to give a sense of context to readers unfamiliar with that period of Britain’s cultural history. I hugely enjoyed meeting and talking with these people, whose cultural and political autobiographies were full of energy, rebellion, fun, with music at the heart. Thank you. Some—Jeff Nuttall, George Melly—are, sadly, now dead.

I edited responses, and structured them here according to the main issues I asked about and to key points that seemed to recur from different interviewees. There is a short-ish introduction to give a sense of context to readers unfamiliar with that period of Britain’s cultural history. I hugely enjoyed meeting and talking with these people, whose cultural and political autobiographies were full of energy, rebellion, fun, with music at the heart. Thank you. Some—Jeff Nuttall, George Melly—are, sadly, now dead.

Material from these interviews, and the second set above I undertook a year or two later with modern jazzers and enthusiasts (I acknowledge that the distinction between trad and modern doesn’t always bear scrutiny) was included in Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain (Duke University Press, 2005).

Interviewees include:

* George Melly

* Jeff Nuttall

* Val Wilmer

* members of the Ken Colyer Trust

* members of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.