[from my Live Music Exchange AHRC conference keynote lecture in Cardiff, November 10 2012, where I talked about the pop festival in the context of the music industry, but also of its sense of place]

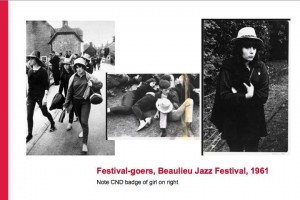

… As we have seen with Beaulieu Jazz Festival in the New Forest in Hampshire from the 1950s, I think there is more to festival place than the upward-striving flagpole—heavenly verticality—or the colourful big top—hippies saying: ‘you’re never too old for a happy childhood’. Indeed when Lord Montagu got involved in the impressive billing of the 1963 Manchester Jazz Festival, the importance of the genius loci of Beaulieu and the New Forest can be glimpsed: when offered the industrial urban north of Manchester instead of the bucolic New Forest, audiences, ironically prompted by the presence in publicity of Montagu connecting this festival with the earlier Beaulieu ones, refused and the event flopped.

… As we have seen with Beaulieu Jazz Festival in the New Forest in Hampshire from the 1950s, I think there is more to festival place than the upward-striving flagpole—heavenly verticality—or the colourful big top—hippies saying: ‘you’re never too old for a happy childhood’. Indeed when Lord Montagu got involved in the impressive billing of the 1963 Manchester Jazz Festival, the importance of the genius loci of Beaulieu and the New Forest can be glimpsed: when offered the industrial urban north of Manchester instead of the bucolic New Forest, audiences, ironically prompted by the presence in publicity of Montagu connecting this festival with the earlier Beaulieu ones, refused and the event flopped.

And I think place is one of the key reasons why, say, Glastonbury Festival endures, and indeed thrives. (Not a festival of the 1960s at all but really of the 1980s, the Thatcher years, of  course.) It’s the genius loci, the spirit of the place, that attracts or resonates. The earlytwentieth century occultist, writer and ethical vegetarian Dion Fortune centred most of her energies around Glastonbury, and was responsible for coining the phrase ‘Avalonians’ to describe the collection of like-minded souls, eccentrics, believers who congregated there looking for spiritual fulfilment. From Arimathea (and where is / was that? No-where—utopia) to Arthur and Avalon—what was it Fortune said of Glastonbury: ‘the veil is thin here’. When I interviewed him for my 2000 book, Glastonbury: A Very English Fair, the senior police officer responsible for security at the festival said to me: ‘You’ve got to remember, it is the Vale of Avalon’ (Veil / vale.) When I sent him the interview transcription he asked me to change that line, because, although it was what he felt, it also made him sound a bit hippy-dippy. I changed it.

course.) It’s the genius loci, the spirit of the place, that attracts or resonates. The earlytwentieth century occultist, writer and ethical vegetarian Dion Fortune centred most of her energies around Glastonbury, and was responsible for coining the phrase ‘Avalonians’ to describe the collection of like-minded souls, eccentrics, believers who congregated there looking for spiritual fulfilment. From Arimathea (and where is / was that? No-where—utopia) to Arthur and Avalon—what was it Fortune said of Glastonbury: ‘the veil is thin here’. When I interviewed him for my 2000 book, Glastonbury: A Very English Fair, the senior police officer responsible for security at the festival said to me: ‘You’ve got to remember, it is the Vale of Avalon’ (Veil / vale.) When I sent him the interview transcription he asked me to change that line, because, although it was what he felt, it also made him sound a bit hippy-dippy. I changed it.

But other festival sites, land plots for the temporary event, include:

- some rural events spaces, such as country showgrounds more commonly peopled by horticultural events (the early Bath Blues Festivals that inspired Michael Eavis, at Shepton Mallett),

- or underused horse-race courses (Plumpton 1970)

- derelict or neglected airfields (Watchfield People’s Free Festival 1975—a redundant military site donated by the government, by the way; Blackbushe Aerodrome 1978 when Dylan played his first UK gig for years; Phoenix Festival Long Marston, mid 1990s),

- on an old rubbish tip (the first Reading, 1971. No jokes, that’s not fair),

- industrial waste land (Bickershawe Lancs 1972, with Grateful Dead)

- blasted heathland (Krumlin, Yorkshire Moors, 1970: people are treated for exposure in hail and sleet. In August. Ginger Baker offers to pay for free on Sunday but there’s no one left),

- out-of-season holiday camps,

- and from the autonomous political perspective: squatted or land-grabbed commons (Castlemorton Common 1992, the culmination of the free rave / festival revival crossover).

Depending on how favourably you view it, the town, the place of Glastonbury itself offers either a cluster or a hotch-potch of utopian and New Age themes and alternative histories. A primary economic activity of the town outside festival is religious tourism. If we buy a ticket for the festival—2013 sold out in record time—we buy into a little bit of Glastonbury, its mystical magic, its palimpsestic fictions, its topography. (Even when the festival doesn’t happen, it happens: in 2012, Glastonbury Tor and its musics moved east as Mount Olympus in Stratford instead.) Is Glastonbury possessed of (or by) a genius loci? Its legends are interwoven with its landscape, the tor, its wells. Is it a hyperactive text machine, where stories produce stories in a labyrinthine, Borgesian world? Father Aelre Watkin remarked to the Arthurian scholar and Glastonbury resident Geoffrey Ashe: ‘You have only to tell some crazy tale at Glastonbury and in ten years’ time it’ll be an ancient Somerset legend’. You may find that taking a pinch of our daily crystal, salt, can help to clear the mists of Glastonbury.

Landscape and landscape interventions are atavisms enhanced and multiplied: let’s locate the stage right here, said the dowser, on this ley line; the sight line along the valley must offer for festival-goers a view the Tor and St Michael’s Tower; build then rebuild the stage in the shape of a, er, ancient pyramid; let’s make a neo-neolithic stone circle up in the green fields….

Landscape and landscape interventions are atavisms enhanced and multiplied: let’s locate the stage right here, said the dowser, on this ley line; the sight line along the valley must offer for festival-goers a view the Tor and St Michael’s Tower; build then rebuild the stage in the shape of a, er, ancient pyramid; let’s make a neo-neolithic stone circle up in the green fields….

One reply on “A sense of place and genius loci at the British pop festival”

[…] A sense of place and genius loci at the British pop festival: Professor George McKay presents an extract from his keynote address at Live Music Exchange Cardiff, covering the history of the British music festival, on his blog. […]