In the run up to Remembrance Sunday in Britain each November the socially symbolic power of the flower is widely evident. It’s an issue I wrote about historically in my 2011 book Radical Gardening: Politics, Idealism & Rebellion in the Garden, which has a chapter on flowers, gardens and the peace movement (specifically, the white poppy, the Peace rose, and the peace garden movement). I saw a friend the other day wearing both the red poppy of the Royal British Legion and the white poppy of the Peace Pledge Union in a lapel—the dialogue or opposition of symbolism between red and white flower, the implicit and explict political positions inscribed in each and the complicated negotiation and qualification of those positions by those wearing them.

In the run up to Remembrance Sunday in Britain each November the socially symbolic power of the flower is widely evident. It’s an issue I wrote about historically in my 2011 book Radical Gardening: Politics, Idealism & Rebellion in the Garden, which has a chapter on flowers, gardens and the peace movement (specifically, the white poppy, the Peace rose, and the peace garden movement). I saw a friend the other day wearing both the red poppy of the Royal British Legion and the white poppy of the Peace Pledge Union in a lapel—the dialogue or opposition of symbolism between red and white flower, the implicit and explict political positions inscribed in each and the complicated negotiation and qualification of those positions by those wearing them.

Extract from Radical Gardening: ‘The … red poppy was adopted as a symbol of memorialising the military dead in the wake of World War One, inspired by the cornfield poppies growing across European battlefields—… the poppy [became] a symbol of remembrance and quickly fund-raising first in the United States, for US veterans—the early petals made of red silk—and then on a larger scale for the

Extract from Radical Gardening: ‘The … red poppy was adopted as a symbol of memorialising the military dead in the wake of World War One, inspired by the cornfield poppies growing across European battlefields—… the poppy [became] a symbol of remembrance and quickly fund-raising first in the United States, for US veterans—the early petals made of red silk—and then on a larger scale for the  reconstruction of France, and then in Britain…. The Royal British Legion first adopted the red poppy for the Armistice Day ceremonies of November 11, 1921. 1.5 million were made, which sold out almost immediately, raising over £100,000 for Legion work supporting British veterans.’

reconstruction of France, and then in Britain…. The Royal British Legion first adopted the red poppy for the Armistice Day ceremonies of November 11, 1921. 1.5 million were made, which sold out almost immediately, raising over £100,000 for Legion work supporting British veterans.’

Today the red poppy is a remarkable symbol, and the only visible social/political signifier permitted (or, troublingly perhaps, expected) to be worn by members of the police force, the armed services. Is it, as Prince William argued in 2011, ‘a universal symbol of remembrance’ (emphasis added)? In Britain it does seem almost universal—look only at the way media confirms the poppy’s place: BBC television journalists wear one (see image below), the Daily Telegraph sports one on its title  banner in the week leading up to Remembrance Sunday, Google (.co.uk at least) has one on its homepage on 11 November.

banner in the week leading up to Remembrance Sunday, Google (.co.uk at least) has one on its homepage on 11 November.

The poppy has curious qualities though, as Professor Paul Gough has pointed out (see his Places of Peace project website): it is, after all, a ‘symbol of unpredictable growth, ephemerality and the sleep of reason’. It appears open to interpretation, too: in 2010, on an official visit to China, members of the UK government were asked by the Chinese to remove their red poppies, which were seen by the Chinese as symbols of imperial military aggression, recalling so clearly in Chinese eyes the 19th century Opium Wars between Britain and China.

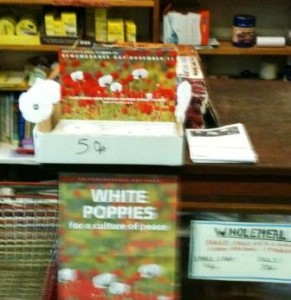

Radical Gardening: ‘The extraordinary success of the red poppy as a symbol of war memorialisation and a tribute to the war dead, as well as a fund-raiser for veterans and their families, saw it also become a focus of some contestation from anti-war activist groups…. An  alternative symbol of remembrance to the red poppy, designed to draw attention to peace not war, and to international rather than national or patriotic deaths, was indeed produced within a few years in the form of the white poppy. Interestingly this recalled the visual symbol of the public accusation of cowardice during World War One, the white feather, primarily distributed by women. The white poppy was initiated by the Women’s Co-operative Guild, a Victorian feminist organisation whose members were involved in the significant gendered social movement international campaigning against war before and after World War One. The first white poppies appeared on lapels in 1933, with the word

alternative symbol of remembrance to the red poppy, designed to draw attention to peace not war, and to international rather than national or patriotic deaths, was indeed produced within a few years in the form of the white poppy. Interestingly this recalled the visual symbol of the public accusation of cowardice during World War One, the white feather, primarily distributed by women. The white poppy was initiated by the Women’s Co-operative Guild, a Victorian feminist organisation whose members were involved in the significant gendered social movement international campaigning against war before and after World War One. The first white poppies appeared on lapels in 1933, with the word  “PEACE” on the flower’s centre…. The wearing of the white poppy … was popularised in succeeding years by the Peace Pledge Union, founded in 1934 (and still campaigning “300 wars later”, as the PPU puts it soberly). There is a politics not only of pacifism behind these coloured paper flowers—gender and nationhood are involved too.’ Today in Britain over 40 million red poppies are sold annually; around 50-60,000 white poppies.

“PEACE” on the flower’s centre…. The wearing of the white poppy … was popularised in succeeding years by the Peace Pledge Union, founded in 1934 (and still campaigning “300 wars later”, as the PPU puts it soberly). There is a politics not only of pacifism behind these coloured paper flowers—gender and nationhood are involved too.’ Today in Britain over 40 million red poppies are sold annually; around 50-60,000 white poppies.

I keep thinking of the English Victorian poet Gerald Manley Hopkins, whose poem ‘Peace’ was finally published long after his death, in, well, in fact, 1918: ‘… piecemeal peace is poor peace. What pure peace … / allows the death of it?’ Wonderful lines, stark questioning: poor / pure peace.