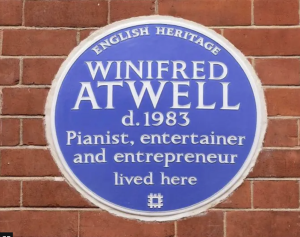

On the fine occasion of a new English Heritage blue plaque to commemorate the achievements of the wonderful 1950s pioneering Trinidadian honk-tonk jazz piano player, chart-topping hit pop star, and groundbreaking television presenter Winifred Atwell this week, I thought it would be fitting to put some of my own published research on Winnie out there.  Want to find out more about her? I first wrote about her over 20 years ago in my book about jazz in Britain, Circular Breathing (laughably, some of the reviews were dismissive of me including her in jazz history). She took hold of me; I think I kind of came to love Winnie. So I returned to her a decade ago in a chapter for the book Black British Jazz. I called this chapter ’16 hit singles and a “blanket of silence”‘, for Winnie did indeed have 16—16!—hit singles in Britain, she was in the pop charts for nearly 120 weeks, she had her own named show on both the UK television channels of the day. Read that chapter here, free. Yet British jazz history (has) ignored her. As I wrote,

Want to find out more about her? I first wrote about her over 20 years ago in my book about jazz in Britain, Circular Breathing (laughably, some of the reviews were dismissive of me including her in jazz history). She took hold of me; I think I kind of came to love Winnie. So I returned to her a decade ago in a chapter for the book Black British Jazz. I called this chapter ’16 hit singles and a “blanket of silence”‘, for Winnie did indeed have 16—16!—hit singles in Britain, she was in the pop charts for nearly 120 weeks, she had her own named show on both the UK television channels of the day. Read that chapter here, free. Yet British jazz history (has) ignored her. As I wrote,

the fact is, Atwell is significant. Her continued exclusion, into the twenty-first century, raises questions about the construction of jazz in Britain. In particular, there are compelling social questions, of gender—Atwell as the symbol of the non-place of women in (masculine) jazz (history)—of class—her middle-class respectability and establishment aspirations (all those Royal Command Performances)—and of race—her role as, at most, quiet commentator on racial politics alongside her groundbreaking high-visibility black media and music profile.

There are musical questions as well, the most pressing of which include repertoire, and the suggestion that some retrospective jazz forms (such as New Orleans collective improvisation) may be deemed more acceptable in jazz history than others (boogie-woogie).

Also Atwell stands as a sonic signifier of jazz’s unease with ‘light music’—and then, at the same time, because it can be such an insecure form, jazz’s periodic discomfort with classical training and all-round musicality, which Atwell had in abundance. Atwell seems to embody jazz’s uncertainty about its own cultural location, which may finally explain the music’s distrust at Atwell’s commercial success (she just had too much), which in itself grates with jazz’s regular self-identification at the margins.

Such questions as these are not necessarily discrete and may of course be interrelated: one of the markers of Atwell’s stage presence, her performance strategy, was her extravagant ball gowns. Her stage gowns speak of her gender, her class, her place in the scheme of things as an establishment variety artiste—and also they do not speak a jazz discourse, particularly for an instrumentalist…. Not for Atwell the contemporary jazz dressing of, say, the sharply suited be-bopper, or the waistcoated tradder, each of which was becoming a recognised sartorial marker of those British jazz times.

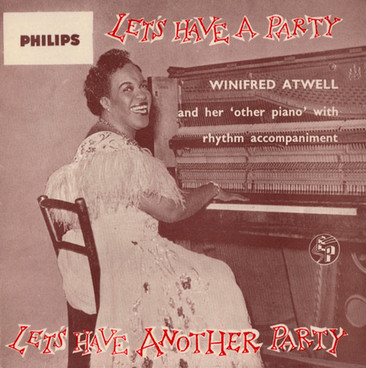

How I wish I’d been invited to the blue plaque ceremony … I would so love to have celebrated Winnie more. Remember that 1954 EP, ‘Let’s have a party’, b/w ‘Let’s have another party’? I wanted to do both of those. Go Winnie!