A journalist from a national newspaper contacted me last week, for my views on recent protests. We then had an email exchange, in which I responded to his further prompts. I wonder what, if any, will be used:

Thanks–would be good to get your views on UK Uncut. The tax system as a focus of political activism isn’t in itself new of course: from the Chartists in the 1830s on the tactic of tax refusal has been of interest to protestors, not least because–in theory, if enough people do it–it hits the state directly in its pockets. In the peace movement too at various times people have practised a form of civil disobedience by witholding the percentage of their tax they calculate as being spent by the government to support the military. The anti-Poll Tax campaigners of the early 1990s often referenced as far back as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 to show a radical tradition of anti-tax resistance. And the car lobby’s extraordinarily successful coming together a few years ago to bring the country to a standstill by blockading petrol stations and distribution depots was largely a reaction to what its campaigners viewed as excessive fuel tax.

Thanks–would be good to get your views on UK Uncut. The tax system as a focus of political activism isn’t in itself new of course: from the Chartists in the 1830s on the tactic of tax refusal has been of interest to protestors, not least because–in theory, if enough people do it–it hits the state directly in its pockets. In the peace movement too at various times people have practised a form of civil disobedience by witholding the percentage of their tax they calculate as being spent by the government to support the military. The anti-Poll Tax campaigners of the early 1990s often referenced as far back as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 to show a radical tradition of anti-tax resistance. And the car lobby’s extraordinarily successful coming together a few years ago to bring the country to a standstill by blockading petrol stations and distribution depots was largely a reaction to what its campaigners viewed as excessive fuel tax.

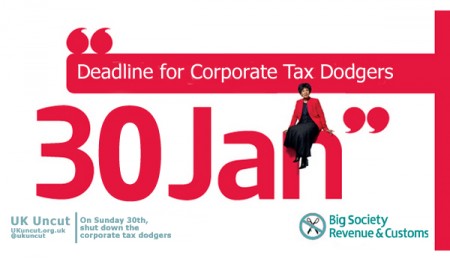

Nonetheless UK Uncut is a fascinating development–not about tax refusal or resistance as many previous tax-centred protests such as those above, but public activism in order to get other people to pay more tax.

Also the fact that the chosen space of the UK Uncut protest is the shop itself–not in the street, or a march winding up at a public park for a rally, say–but within the shop, is important. There is an effort to blockade, to obstruct, a normal everyday place where financial exchange and profit-making happens: in the  shop. Our national leisure activity and even our sense of national identity (‘a nation of shopkeepers’) is nudged, ever so slightly. Fascinating. I’m not sure how anti-consumerist this is–it’s not a ‘Buy Nothing Day’-style campaign as a radical critique of consumption. And yet in another way it does strike at the very transactional heart of capital, at the micro-moment when money changes hands. Because it’s about the international tax avoidance strategies of major companies, and what is seen as their over-cosy relationship with government and HM Revenue, the campaign aims to widen its target too: national government cuts, transnational capital business arrangements.

shop. Our national leisure activity and even our sense of national identity (‘a nation of shopkeepers’) is nudged, ever so slightly. Fascinating. I’m not sure how anti-consumerist this is–it’s not a ‘Buy Nothing Day’-style campaign as a radical critique of consumption. And yet in another way it does strike at the very transactional heart of capital, at the micro-moment when money changes hands. Because it’s about the international tax avoidance strategies of major companies, and what is seen as their over-cosy relationship with government and HM Revenue, the campaign aims to widen its target too: national government cuts, transnational capital business arrangements.

I’m also interested in expanding on these areas:

–Are we at a tipping point regarding levels of anger and discontent among Britons that could see a return to violent protest on a scale not seen since 19xx? Hmm. There is ‘violence’ (your word) and ‘violence’ in politics–a short urban riot, possibly even one that seems to be encouraged by some controversial police crowd control methods, is hugely different to, say, the use of the bullet in Northern Ireland–but in recent decades each has been a form of violent protest. We need to be careful in our terminology here [and aware of distinctions]. But I do acknowledge the extraordinary event of a member of the royal family being assaulted in a demonstration–that story shot around the world’s media as a microcosm of the current state of turmoil in British society. Does that mean Class War and Bash the Rich events are going to make a comeback, as in the Thatcher years? We have already seen reporting of radicals organising protests against the forthcoming royal wedding. At the same time,… as the peace activist whispering in my ear has just pointed out, the greatest violence Britons are involved in currently is a state-sanctioned war.

But there could be an alternative coalition which organises itself to harness the discontent and anger–across the public services, trade unions, students and schoolchildren, the disabled, all the kinds of groups feeling targetted by government policies. As one tweet put it on UK Uncut’s website today: ‘Only 7 weeks to mobilise 1 million united people onto the street[s] of London on March 26th’.

—What’s your greatest concern about all this? My concern is that the campaign as it develops, and assuming it expands, will not be listened to by the government–a little like when one million people marched through London against the war in the biggest street protest ever in Britain, and the government ignored them. That’s a real danger for democracy as a general system because democracy is refreshed and revitalised by protest, a government is kept on its toes by people on the streets. And there is a tremendous groundswell of interest in politics which at the moment no established political party seems capable of harnessing. While we regularly bemoan the public’s apathy towards politics, here is in fact a wide-ranging set of groups and campaigns with energy and drive, many of whom might never have been involved before. For the political process, its discourses and actions, that ought to be a positive situation.

One reply on “UK Uncut: A Very British Protest?”

Here is how it works.

Companies that operate in the UK pay tax upon their UK profits, they pay VAT, they pay national insurance on their UK staff’s salaries and those staff pay income tax. They will pay local business rates on their premises.

Where the company is headquartered if it is a multinational determines what happens to their earnings once taken out of each country they do business in. It is generally a good thing to have multinational headquarters as you will gain extra tax revenue, but also because they use lots of other expensive goods and services, and employ the well paid staff. If the headquarters of a firm is in the UK then they will likely use a UK law firm, a UK accountant, UK IT consultants, etc, etc.

The issue many people have is with tax rules that basically allow you to massively reduce your tax liability in the UK (and elsewhere) by various methods, often involving loans. Loan interest payments aren’t taxed (quite sensibly) but this can be abused by using an offshore headquarters. So the owning company which is based in the British Virgin Islands “lends” lots of money to its UK subsidiary which makes regular interest payments back to the owning company. Those interest payments happen to coincide with the profits the British subsidiary makes, which basically reduces its profits to 0 and therefore reduces its tax liability massively. The BVI company has very healthy profits but in a country that doesn’t tax them.

The real kicker is that these headquarters that are making all the profits and pay zero tax are often held under nominee directorships, so you cannot find out the real private owners..

The bank address for the offshore headquarters company can be anywhere. It does not have to also be in the offshore country.

The company nominee directors have direct access to this bank account to do what they want.

This is because the offshore havens do not require the accounts to be audited or even for accounts to be submitted in general.

Ironically the “EU Tax savings directive” passed in 2008 stopped the ability of private individuals to do this. They did this by forcing all countries’ banks to expose all persons’ accounts everywhere to the other governments. This was led by the main progressive tax countries of course to stop personal tax liabilities moving offshore.

It’s painfully ironic what is going on. Think about the scale of the damage this causes and the ripple effects it has and it’s staggering.

Talk to any London accountant you have known for 5 or more years and they will tell you this in detail. If you don’t have a long standing relationship with them then they are unlikely to discuss this dirty laundry with you.