As a part of the publicity for Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability 3-4 years ago I produced a Top Ten songs of disability. No. 10 was the Who’s ‘Tommy’. I received some cross correspondence from another popular music scholar with family experience of disability (a disabled child, as I remember), who criticised the inclusion of such an, in his view, mocking piece, a song which was a(nother) high-profile travesty of disability culture and expression. I have been hugely intrigued to see this production of Tommy, by Ramps on the Moon in collaboration with Graeae Theatre Company, the leading UK theatre group for deaf and disabled artists.

As a part of the publicity for Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability 3-4 years ago I produced a Top Ten songs of disability. No. 10 was the Who’s ‘Tommy’. I received some cross correspondence from another popular music scholar with family experience of disability (a disabled child, as I remember), who criticised the inclusion of such an, in his view, mocking piece, a song which was a(nother) high-profile travesty of disability culture and expression. I have been hugely intrigued to see this production of Tommy, by Ramps on the Moon in collaboration with Graeae Theatre Company, the leading UK theatre group for deaf and disabled artists.

In Shakin all Over I wrote about ways in which bands like the Who could ‘explore and return to tropes of disability over lengthy pop careers.’

[They] stuttered the attitudinal voice of English youth in 1964’s ‘My generation’ (‘People try to put us d-d-down’), sang and acted ‘That deaf dumb and blind kid [who] sure plays a mean pinball’ in [Tommy], while guitarist Pete Townsend was widely reported when he spoke out recently about the experience and the dangers of rock music-induced hearing loss: ‘I have unwittingly helped to invent and refine a type of music that makes its principal proponents deaf.’

From youthful stutter to a hearing impairment more readily associated with older people, from the band that first sang, when they were young, ‘I hope I die before I grow old’ (it didn’t happen, not to the songwriter or the singer, anyway): cripping the Who offers us a different set of insights into the band’s body of work across the decades, which is also to do with refiguring the generational pull of youthful pop and rock. As singer Roger Daltrey said in 2006: ‘Can you see us onstage in wheelchairs?… It will still be us, still be the same music.’

Tommy was first a rock opera in 1969, then a musical film in 1975 (directed by Ken Russell), then a stage musical in 1993. Director Kerry Michael tells us in the programme that the aim with this new production has been to integrate ‘an exciting and inclusive disability aesthetic.’ The photomontage of disability activism shots at the start was I thought a bit clunking, nor did it really fit with the narrative to follow; perhaps it’s intended as a corrective to the musical’s own skewed representation of disability.

Tommy was first a rock opera in 1969, then a musical film in 1975 (directed by Ken Russell), then a stage musical in 1993. Director Kerry Michael tells us in the programme that the aim with this new production has been to integrate ‘an exciting and inclusive disability aesthetic.’ The photomontage of disability activism shots at the start was I thought a bit clunking, nor did it really fit with the narrative to follow; perhaps it’s intended as a corrective to the musical’s own skewed representation of disability.

This version is mostly the 1993 stage musical one, with an additional song and some extra lyrics especially produced by Who guitarist and original writer Pete Townshend. (The additional song, a bluesy lament for lost youth and spark from an old performer—so surely it’s about Townshend himself, or Daltrey…—is for the Acid Queen to give her (here, him) a presence in Act II.) This matters because the original ending was changed: from Tommy urging his followers to become ‘deaf, dumb and blind’ like him as a route to enlightenment, to a cosier one in which we are urged not to be like Tommy, but to look for our own inner strengths. I should say that the end felt uplifting and moving for us last night, as, with house lights up, the entire cast sang and signed to us a message of inclusion and understanding. If that sounds corny, it really wasn’t.

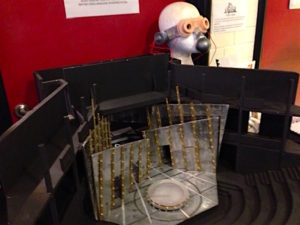

The infrastructure of inclusion around the performance may be kind of standard for Graeae-style productions—a stage model and costumes props in the foyer for visually impaired theatre-goers (right), hearing loops, surtitles, signing, and more—but it does also regularly challenge much everyday theatre practice or rhetoric of inclusion.

The infrastructure of inclusion around the performance may be kind of standard for Graeae-style productions—a stage model and costumes props in the foyer for visually impaired theatre-goers (right), hearing loops, surtitles, signing, and more—but it does also regularly challenge much everyday theatre practice or rhetoric of inclusion.

Notwithstanding the massive flaws in the original story—psychical crisis makes boy multiply disabled, then it becomes a satire on religion and the counterculture? Plus, today for younger audience members (there weren’t that many tbh last night): what is a ‘pinball’?—this Tommy is terrific. It’s full of energy and movement, and only a couple of the large deaf and disabled cast seem to perform as though they are auditioning for Glee or Hairspray. The live band, centre stage at the back, is tight and loud.

Especially in Act I, exploring the musical via a disability aesthetic shines through. What really strikes convincingly are some of the experiences of youthful disability: the medicalisation of the disabled body (tests, tests, and anxiety about tests), the bullying and abuse of the vulnerable. The sexual abuse of Tommy by Uncle Ernie as he sings ‘Fiddle about’, played by two hands spot-lit on an otherwise darkened stage, is powerful. Here the disability aesthetic makes full sense. Also there are some great hi-energy ensemble numbers (‘Pinball wizard’ overwhelms the stage) and other, well, weird ones (‘The Acid Queen’ as a coked-up Labelle in drag, feat. star turn Peter Straker, who appeared as the Narrator in Tommy in the 1970s).

Especially in Act I, exploring the musical via a disability aesthetic shines through. What really strikes convincingly are some of the experiences of youthful disability: the medicalisation of the disabled body (tests, tests, and anxiety about tests), the bullying and abuse of the vulnerable. The sexual abuse of Tommy by Uncle Ernie as he sings ‘Fiddle about’, played by two hands spot-lit on an otherwise darkened stage, is powerful. Here the disability aesthetic makes full sense. Also there are some great hi-energy ensemble numbers (‘Pinball wizard’ overwhelms the stage) and other, well, weird ones (‘The Acid Queen’ as a coked-up Labelle in drag, feat. star turn Peter Straker, who appeared as the Narrator in Tommy in the 1970s).

The New Wolsey Theatre has a fruitful collaborative partnership with Graeae Theatre Company. (I wish my own city, regional rival Norwich, had such a dynamic small theatre, really.) I saw Graeae’s brilliant Ian Dury jukebox musical Reasons to be Cheerful here a few years ago, drove down from Lancaster for that. Was thrilled to then see on tv the band reprise ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ live at the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Paralympics. Graeae are a company to be cherished.

In Tommy, several lead parts are played by deaf actors—Tommy, his mother Nora. Nora has a singing double, Tommy has two singing doubles. In the performing world of what Ian Dury called Normal Land disabled actors and musicians often still don’t get a look in (even when the character is meant to be disabled, for Goodness’ sake), half a part, no part at all, crip part given to TAB actor. On Stage Graeae, a disabled actor can require two or even three human presences. There is I feel a powerful statement of cultural value in that prosthetic gesture, which speaks of solidarity and love. Bravo, brava.