My awareness within the record of ‘Spasticus’ wasn’t a shared awareness amongst ‘walkie-talkies’, so I obviously knew there was a risk that I was going to alienate a lot of people and they were going to get the hump with me, [saying] ‘What’s this fucking spazzer doing moaning?’ Well I wasn’t moaning, I was actually doing the opposite of moaning. I was yelling. – Ian Dury

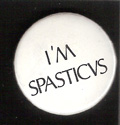

As Ian Dury’s first single since leaving the independent Stiff Records for the major label Polydor, 1981’s ‘Spasticus Autisiticus’ was a provocative, or even perversely self-destructive, choice. The timing was clear enough: it was a considered public response by a disabled pop star to the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons. But in fact we can and should go further—to release it as a single (let alone that it was on a new label, and with a new band) was an extraordinary, and brave, if also frankly career-shattering move on Dury’s part. A Sly and Robbie-backed Jamaican dance-rhythm pop song about spastics, released as a single, with a political message and a powerful and discomforting accusation?

As Ian Dury’s first single since leaving the independent Stiff Records for the major label Polydor, 1981’s ‘Spasticus Autisiticus’ was a provocative, or even perversely self-destructive, choice. The timing was clear enough: it was a considered public response by a disabled pop star to the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons. But in fact we can and should go further—to release it as a single (let alone that it was on a new label, and with a new band) was an extraordinary, and brave, if also frankly career-shattering move on Dury’s part. A Sly and Robbie-backed Jamaican dance-rhythm pop song about spastics, released as a single, with a political message and a powerful and discomforting accusation?

In my new book, Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (2013, folks), we see that Dury was happy to use language and even to produce music that could make people ‘wince’, not least (though not only) when he wrote songs about disability. Having said that, the lyrics of ‘Spasticus’ are not sprinkled with the swear words so common elsewhere in Dury’s oeuvre; much of their power comes from their startling simplicity, as here describing bodily imperfection and malfunction or mobility difficulties.

I widdle / when I piddle / ‘cos my middle / is a riddle…. / I’m knobbled / on the cobbles / ‘cos I hobble / when I wobble.

Yet the BBC did indeed ban the song (in fact the corporation had previously banned the 1977 Dury single ‘Sex & drugs & rock & roll’, so he did have a track record of controversy), though only until a 6 p.m. watershed, a decision which itself irked Dury. His record label subsequently sought to strike a defiant as well as sophisticated note regarding the record’s failure to chart, releasing a statement which said: ‘Just as nobody bans handicapped people—just makes it difficult for them to function as normal people—so “Spasticus Autisticus” was not banned, it was just made impossible to function’.

There were also protests about the song from the primary British charitable organisation responsible for the support and care of people with cerebral palsy, then known as the Spastics Society. Rather than a musical act of self-empowerment and the reclamation of abject terminology by a high profile disabled artist, the Spastics Society heard a controversial singer confirming by aggressive repetition in the song’s chorus the common playground insult. (It is interesting that the Spastics Society was no more successful than Dury at the time in overcoming the stigmatised meaning of the word ‘spastic’ in everyday parlance; today the organisation has rebranded itself as Scope.)

Further, on an Australian tour in 1982 the authorities in Brisbane threatened to have Dury arrested if he played ‘Spasticus’ live; of course he did it anyway. So a major part of the afterlife of ‘Spasticus’ has been in the context of its (partial) censorship: in the 1990s it appeared variously on a CD included with an Index on Censorship special edition entitled ‘The Book of Banned Music’ (1998), and on a Channel 4 television documentary on the top ten banned records in popular music history.

We might think that the removal of ‘Spasticus’ from what Dury called ‘the polio folio’ to be stored in the censorship file was one more act of making it ‘impossible to function’. Yet its drama can be replayed, and without loss of power. A 2012 musical play based around Dury’s songs, entitled Reasons to be Cheerful, was produced by Graeae, Britain’s leading theatre company for people with disabilities. There is a wonderful frame-breaking moment where one actor explains to the audience that, when he was a youth, John Kelly, one of the lead singers in the play, had been so outraged by the BBC’s response to ‘Spasticus’ that he wrote to the head of the organisation. Prompted, Kelly tells us the contents of the letter: ‘Dear Director-General of the BBC, you’re a cunt’. Following the laughter Kelly continues, with feigned surprise, ‘And I never even got a reply’.

We might think that the removal of ‘Spasticus’ from what Dury called ‘the polio folio’ to be stored in the censorship file was one more act of making it ‘impossible to function’. Yet its drama can be replayed, and without loss of power. A 2012 musical play based around Dury’s songs, entitled Reasons to be Cheerful, was produced by Graeae, Britain’s leading theatre company for people with disabilities. There is a wonderful frame-breaking moment where one actor explains to the audience that, when he was a youth, John Kelly, one of the lead singers in the play, had been so outraged by the BBC’s response to ‘Spasticus’ that he wrote to the head of the organisation. Prompted, Kelly tells us the contents of the letter: ‘Dear Director-General of the BBC, you’re a cunt’. Following the laughter Kelly continues, with feigned surprise, ‘And I never even got a reply’.

And now, at the Paralympics opening ceremony in east London (where Ian ‘Oi! Oi!’ Dury would have felt at home, though he was actually a sort of middle-class grammar school boy) last night—co-directed by Graeae’s Jenny Sealey—we see in a quite fabulous scene a segue from one wheelchair user with a unique voice, Professor Stephen Hawking, to another, John Kelly, while disability rights activists wave banners around. And Kelly is singing—yes, he really is!—live for the television millions ‘Spasticus’, with its lyrics captioned on screens round the stadium. So very, very moving and a tremendously powerful musical moment. (Of course, we’d had musical crips at the Olympics opening ceremony too: the deaf percussionist Evelyn Glennie playing live, and punk sneerer Johnny Rotten on record.) Hallo to you out there in Normal Land: possible to function.

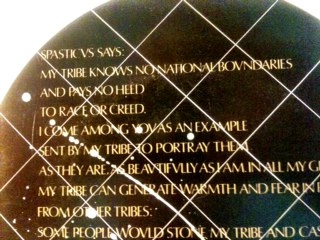

We must too remember the important poem, a speech by the character Spasticus, on the back cover of the picture sleeve for Dury’s original single:

We must too remember the important poem, a speech by the character Spasticus, on the back cover of the picture sleeve for Dury’s original single:

SPASTICVS SAYS: / MY TRIBE KNOWS NO NATIONAL BOVNDARIES / AND PAYS NO HEED / TO RACE OR CREED / I COME AMONG YOV AS AN EXAMPLE / SENT BY MY TRIBE TO PORTRAY THEM / AS THEY ARE, AS BEAVTIFVLLY AS I AM, IN ALL MY GLORY / MY TRIBE CAN GENERATE WARMTH AND FEAR IN PEOPLE / FROM OTHER TRIBES: / SOME PEOPLE WOVLD STONE MY TRIBE AND CAST THEM OVT / OTHERS FOSTER AND NVRTVRE WE OF MY TRIBE / THE EXTREME MEMBERS OF MY TRIBE ARE KILLED AT BIRTH / WITHOVT THE AID OF OTHERS MY TRIBE CAN ONLY CRAWL / S L O W L Y / HALLO TO YOV OVT THERE IN NORMAL LAND / WE TOO ARE DETERMINED TO BE FREE

‘Hallo to you out there in Normal Land. We too are determined to be free.’ Wonderful.