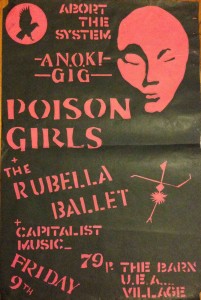

A new collection of essays about anarcho-punk has just been published by Minor Compositions, a series from Autonomedia: Mike Dines and Matt Worley, eds. The Aesthetic of Our Anger: Anarcho-Punk, Politics and Music (2016). The entire book is open access (i.e. freely available) here, but you can also read my short preface to the book by clicking the link below. This extract is taken from the preface (the original poster for the Norwich concert described is right. Yes, I still have it. I found it a year ago, folded neatly in the box set of Crass’s Christ: The Album, as we were packing up our house in preparation for moving south, to, well, back to Norwich after 30 years away. Note that Crass weren’t even advertised to be playing that night).

‘That first time in Norwich, Crass and Poison Girls were astonishing, not just to me, but to all the punks who knew about the gig and had turned up, the more so because the bands were so casual about it, wandering around the half-empty hall before and after playing, wanting us, waiting for us, to talk to them. They were out front drinking tea – I’d never ever seen bands doing that at the end of a gig before. Music was material to them, and they showed that; the performance was an object, clearly delineated, which they involved themselves in and then exited. Music happened for a while and then it didn’t happen. The bands extended the performance entirely and indefinitely, to include the pre- and post-show, the setting up of the PA, the draping of flags and banners and subsequent transformation of the hall, Crass in their problematically paramilitary black garb and red armbands, the sexy sexless women. Either way I was totally intimidated, and deeply attracted. Here were people doing exactly what I thought punk should do, be a force.’

This was me, an eighteen-year-old punk in 1979, having his anxieties that maybe punk wasn’t going to change the world (for the better) after all put on hold for a couple of more years. I’m uncertain how powerfully the sensation lasted. (Occasionally, yes, I can still express that sentence today as: I’m uncertain how powerfully the sensation has lasted.) It was the laying out and laying bare of ideals, culture and event presented in a total package that I fell for in that old barn that night. Nine or ten months later, the same bands played a small hall in Suffolk, a benefit gig for local peace groups. There were clashes in the sleepy market town between outsider punks and local bikers, and the bikers circulated around the hall brandishing chains waiting for lone punks to attack.

‘Plenty of people in the crowd – me included – aren’t interested in this at all; we want to see the bands, experience the whole Crass & Poison Girls trip, that sensurround gig of music, TVs, banners, flags, uniforms, wrapped in an unpretentious delivery of the mundane. Disapproving comments are shared as we try to reassure one another, there are sneers at this new mods-and-rockers-style moment, this isn’t punk, we’re here for a pacifist benefit. The transformed church hall is made a site of extreme rhetoric and cultural production for two hours. But outside…’.

The open space of an anarcho-punk gig, where subcultural contestation and negotiation could sometimes take place, where self-determination and self-policing could take a while to work through, operated very poorly for me that night. Six bikers trapped me alone near the train station in the dark after the gig and taught me an unforgettable lesson about the limits of tolerance and freedom among British youth in the countryside. Welcome to anarcho-punk. Rival tribal rebel revels, indeed.

Click this link for the full preface, as well as the book cover and table of contents: mckay-4word-the-aesthetic-of-our-anger.