I had the pleasure last night of attending the private view for a terrific new exhibition about the Jazz Age in Britain, curated by Prof Catherine Tackley. Called Rhythm and Reaction, it’s at Two Temple Place, London until 22 April, and is free. Do go. (A photo/postcard from a 1919 ‘Famous Jazz Band’ in Cheshire which is in my possession is included in the exhibition.)

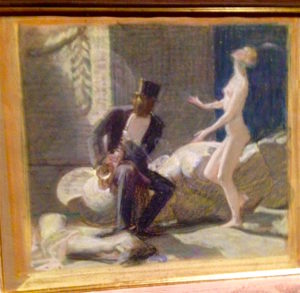

I was most excited about seeing this painting, which is we can say notorious in jazz history. In fact, there are no less three versions of it on display in the exhibition, which was thrilling to see. (This doesn’t include the original, as shown in the Royal Academy in 1926—that was destroyed by the artist himself following the public outrage below.) But this one, a small-ish pastel sketch from 1926, in its roughness and age, really caught my eye. I’ve never seen it before.

It got me thinking again about the jazz story of the painting. In a chapter on whiteness and jazz in 2004’s Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain, I’d drawn on Jim Godbolt’s work on it from his excellent History of Jazz in Britain vol. 1, and followed that up with material supplied to me from the Royal Academy archive. Below is what I wrote about John B. Souter’s ‘The Breakdown’, with a little material at the start to draw the context of jazz and race at the time. (From chapter 2, a section called ‘(White man) in Hammersmith Palais’: jazz, racism, white empires. For references, go to the book.)

‘A reason of state and not of art’ (nor music, of course) indeed…

… Through the 1920s, the Jazz Age, those in the business—of music education, and the burgeoning jazz and dance criticism—arranged themselves to present a solid white line of outrage—a certain sign that consensus was in crisis, transition imminent, and not only in the cultural arena. Jazz was the musical metonym of hegemon. Uniting the authority of Christianity and of an ancient university for the benefit of assembled music teachers, the Rector of Exeter College, Oxford welcomed delegates to a 1926 summer school with the advice: ‘Don’t take your music from America or from the niggers, take it from God, the source of all good music.’ The public racialised discourse of the consumption of jazz in Britain was frequently channelled through the (dancing) body, (black) masculinity and the fascinated threat to white female sexuality. This is evidenced in a Sunday Chronicle article from June 1924 by one Violet Quirk, in which she describes for readers her ‘disturbing impressions’ of a jazz dance.

The negro musicians knew well how to recapture the inflaming noises made by their far-back ancestors, and which are still enjoyed by cannibals during their most important ceremonies.… [T]he animal devotees of jazz, who like to be maddened … [s]ee how it whips them about! They obey it like slaves.… These women … shuffle round the room with striding legs too far apart, rigid bodies, and fixed staring eyes.…

Animals, slaves are whipped. Young white women are enslaved, sexualised, narcotised, through the bodily experience of dancing to that primitive, that cannibalistic music. The transcendent music transports them to Africa, a colonial Africa of white nightmare (the horror), via the jazz dance as some kind of voodoo rite. This is an important point: at this time in Britain black jazz was articulated as a threat within the framework of the imperial experience. It was less to do with America per se than to do with continuing white anxieties about the blackness of empire, and how to control it.

Moreover, the crisis in whiteness was explicitly gendered and generational: it was young (fertile) white women that were depicted as threatened, through an implied miscegenation. Being white and weak was not an acceptable combination in a discourse of British imperial masculinity, but John Bull’s flapper grand-daughter, holder of the future of the white race if she would only realise it, only protect her privileged position as well as her virtue, was the ideal(ised) chosen symbol for the transmission of such neuroses.

In a further sign of the extent to which black jazz had entered the white imagination, and was beginning to impact on what it meant to be white, two years later a controversy led to the withdrawal of a painting from the Royal Academy spring show in London. John B. Souter, a member of the Pastel Society, submitted a painting called ‘The Breakdown’, which showed a naked young white woman dancing as in a trance to the music of a saxophone played by a formally dressed black man, who is sitting on a broken white classical statue.

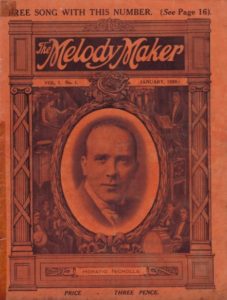

The first editor of Melody Maker (founded that same year, 1926) was Edgar Jackson, real name Edgar Cohen, a London-born Jew. Because of the signified jazz of the saxophone, and probably also for the pragmatic reason that he wished his new publication to be recognised as a mouthpiece for the scene, Jackson felt it his duty to speak out against the painting—on behalf of all British jazz musicians:

We jazz musicians … protest against, and repudiate the juxtaposition of an undraped white girl with a black man.… We demand also that the habit of associating our music with the primitive and barbarous negro derivation shall cease forthwith.… ‘Breakdown’ is not only a picture entirely nude of the respect due to the chastity and morality of the younger generation but in the degradation it implies to modern white woman there is the perversive danger to the community and the best thing that could happen to it is to have it … burnt!

A Royal Academy Annual Report describes what followed.

At the request of the Secretary for the Dominions an oil painting (No. 600) entitled ‘The Breakdown’, by J.B. Souter, was removed from the exhibition on May 8, as the subject … was considered to be obnoxious to British subjects living abroad in daily contact with a coloured population. The gap was filled by a portrait of Lady Diana Manners, by Sir J.J. Shannon, R.A., lent by Violet Duchess of Rutland.

The justification was for the painting’s withdrawal was that it would make difficulties for white officials in the colonies, and indeed the Academy’s Council minutes explain the removal as ‘due to a reason of state and not of art’. That it should have been replaced by such an establishment piece as a portrait of a Lady painted by a Sir and lent by a Duchess suggests an ostentatious desire to re-establish the dominant order following its temporary breakdown.