Salford forgets Ewan MacColl centenary – city icon, famous for writing Dirty Old Town, ignored http://t.co/uurrU9sB8H #ewanmaccoll

— salford star mag (@salfordstar09) January 18, 2015

The boy called Jimmie Miller was born 100 years ago. When he was thirty, he renamed himself Ewan MacColl, and became an influential (yes, and dogmatic) folk-singer, leader of a movement, communist and activist, media innovator, song-writer, husband and co-worker with first Joan Littlewood, and then Peggy Seeger, as well as a co-founder of the Theatre Workshop. Here is a piece of writing, from Shakin’ All Over, about just one of MacColl’s many important cultural productions and collaborations, The Body Blow. (All references / sources are in the book.) It’s offered here in respectful tribute to mark the centenary of his birth which, according to the Salford Star, that terrific alternative media voice in the direct MacColl tradition of political trouble-making, his home city itself surprisingly—disappointingly—seems not to be doing. (Can that be correct?)

… In March 1962 one of the earliest popular music interventions around polio was made, with the broadcast on BBC Radio’s Home Service of Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger and Charles Parker’s ‘radio ballads’. (The previous year MacColl and Seeger had written and sung songs about polio survivors for a 30-minute television feature entitled Four People, which in fact used ‘virtually the same subjects’ for interview as the later radio-ballad.)

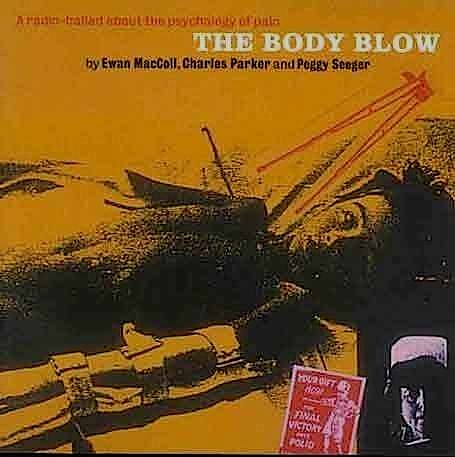

Entitled The Body Blow, this was the fifth in their innovative series of eight documentaries that combined the sound effects of actualité, the original voices of interviewees recorded in situ, and specially composed folk music by MacColl and Seeger. Subjects of the radio-ballads included the working class (train drivers, roadbuilders, fishermen, miners), but also some identity groups at the margins of society (the new teenagers, travellers, and, in The Body Blow, a group of adult polio survivors). Producer Parker explained that he was presenting ‘the intensely personal experience of a group of polio sufferers, with the intention of purging the healthy person’s somewhat atavistic fears of the grievously deformed or disabled’.

Entitled The Body Blow, this was the fifth in their innovative series of eight documentaries that combined the sound effects of actualité, the original voices of interviewees recorded in situ, and specially composed folk music by MacColl and Seeger. Subjects of the radio-ballads included the working class (train drivers, roadbuilders, fishermen, miners), but also some identity groups at the margins of society (the new teenagers, travellers, and, in The Body Blow, a group of adult polio survivors). Producer Parker explained that he was presenting ‘the intensely personal experience of a group of polio sufferers, with the intention of purging the healthy person’s somewhat atavistic fears of the grievously deformed or disabled’.

If the outward aim of the programme was focused on changing the perceptions of the audience towards people with disabilities, the core purpose of the radio ballads in general was to present the authentic voice of the subject. (All five musicians donated their recording royalties for The Body Blow to the Polio Research Fund.)

The Body Blow had an intriguing further result. One of the interviewees, Dutchy Holland, was literally part of the programme’s restorative project; his capacity to speak depended entirely on the phase of his mechanical ventilator (‘he could only speak on the “inspiration” phase of the iron lung’s breath’). But through the recording and editing of Holland’s voice, the programme presented an enabled communication. As the disembodied voice of the radio programme narrator explains approvingly and comfortingly to the listening audience, to Holland’s ‘machine-chopped speech, the tape recorder, with the editing it makes possible, can restore wholeness’. That’s some media programme, to be capable of ‘restoring wholeness’. (Other cultural expressions—such as by those articulating their own experiences—have viewed the mechanical ventilator more intrusively, less as lifesaver or restorer. American polio survivor Mark O’Brien writes in his poem ‘The man in the iron lung’: ‘In its repetitive dumb mechanical rhythm, / Rudely, it inserts itself in the map of my body’.)

Although criticised at the time and more recently, the actual music in this radio ballad has some moments of wonderful effect, notably in the section ‘Can’t breathe’, which juxtaposes the sound and rhythm of the ‘iron lung’ with a pared down instrumentation featuring English concertina (an instrument, of course, in which the sounds are produced by mechanical wind manipulation), and MacColl and Seeger’s contrasting voices singing lyrics in unison about ‘your friendly machine’. The machine’s rhythm sets the tempo for the song, while also faintly and pathetically evoking the sound of waves breaking on a beach; the concertina is played so tentatively that its introductory solo notes sound vulnerable, shaky, about to give way. The lyrics admittedly do veer uncertainly between precise well-expressed detail and sentimentality or melodrama, even in the same verse.

Steel and plastic deputy for lungs / Does your breathing for you night and day. / This small machine, your shield, your sword and buckler, / Holds death at bay.*

[* I am grateful to Nick Hall, my brother-in-law, for his suggestion that the phrase is ‘sword and buckler’ (a buckler is a type of shield), not ‘sword and butler’ as presented in the lyric sheet included with the programme’s CD re-issue and unfortunately repeated by me in Shakin’ All Over.]