An introduction to Radical Gardening, in George McKay’s own words [from press pack]:

An introduction to Radical Gardening, in George McKay’s own words [from press pack]:

Where does this book come from? Over the years I have written extensively about alternative, radical and community cultures, including:

- researching pop, rock and jazz festivals,

- cultures of the peace movement,

- community music,

- and activist politics.

Most of these things appear in gardens in some form, with surprising regularity in fact.

Festivals. Festivals are themselves usually a particular use of the landscape in a rural setting, often selling the idea of the temporary pastoral idyll to an urban public (think of Woodstock in 1969, marketed as a retreat from New York). With the idealism of certain festivals—notably Glastonbury, the CND festival in the 1980s—the festival site becomes a version of ‘polemic landscape’, using the land, trees, fields, to try to evoke or symbolize a different way of thinking, even a different (green) politics.

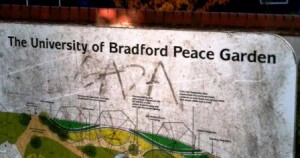

Peace. I was also interested in looking at the way the peace movement used the special green space or symbol of the garden  as part of its cultural protest—the ‘peace garden’ favoured as a statement of anti-nuclearism by socialist local authorities in the 1980s, for instance, but also, historically, going back to the white poppy of the Peace Pledge Union of the 1930s. I wanted quite simply to think about these in the context of challenging what seems to be our current orthodoxy of militarism—to do my little bit to reinsert into public discourse practices of dialogue and negotiation which don’t culminate in aggression, war, death.

as part of its cultural protest—the ‘peace garden’ favoured as a statement of anti-nuclearism by socialist local authorities in the 1980s, for instance, but also, historically, going back to the white poppy of the Peace Pledge Union of the 1930s. I wanted quite simply to think about these in the context of challenging what seems to be our current orthodoxy of militarism—to do my little bit to reinsert into public discourse practices of dialogue and negotiation which don’t culminate in aggression, war, death.

Community. As a musician I’ve often written from that cultural perspective—I’ve described much of my work as ‘cultural studies with a soundtrack’—jazz, rock, pop, punk, rave, and so on. I worked as a community musician in the early 1980s—with hindsight I realize it was an early effort to combine culture, politics, education, areas I’ve stuck with since, really—and co-edited a book about community music a few years ago. So again, when I started thinking about community gardening, allotments, I had something to draw on: the way in which a social and cultural focus might help construct community, might help us redefine it.

Community. As a musician I’ve often written from that cultural perspective—I’ve described much of my work as ‘cultural studies with a soundtrack’—jazz, rock, pop, punk, rave, and so on. I worked as a community musician in the early 1980s—with hindsight I realize it was an early effort to combine culture, politics, education, areas I’ve stuck with since, really—and co-edited a book about community music a few years ago. So again, when I started thinking about community gardening, allotments, I had something to draw on: the way in which a social and cultural focus might help construct community, might help us redefine it.

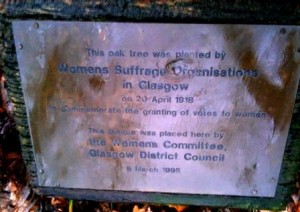

Activist politics. A lot of my work has been about social movements—the way people form campaign groups, make political protest happen, how they use culture to symbolize the campaign and to change society. And gardens figure significantly here, from the simple fact of needing a public park  for the political marchers to wind up at for their speeches and rally, to the invention of Speakers’ Corner as a privileged (and at the same time limited) space for free expression. On the other hand I also looks at the darker side, at the fetishisation of land in, for instance, Nazism, and at the sinister echoes of that in white racist or extreme nationalist movements since. Not every garden is a paradise.

for the political marchers to wind up at for their speeches and rally, to the invention of Speakers’ Corner as a privileged (and at the same time limited) space for free expression. On the other hand I also looks at the darker side, at the fetishisation of land in, for instance, Nazism, and at the sinister echoes of that in white racist or extreme nationalist movements since. Not every garden is a paradise.

And I really loved the idea of all these kinds of big questions—different ways of living, war and peace, community, politics and social change—being situated in the space of the garden or the practice of gardening in some way. I came up with this massively ungainly term to think about these sorts of things: ‘horti-countercultural politics’. Don’t worry, I only use it a couple of times though in the book. In fact, Radical Gardening is more a book about ideas (‘ideologies’ is the word we used to use) in gardens, really. I liked the surprise when I talked with people about the book I was writing: ‘What, in a garden?’