Awesome article by @george_mckay on music festivals & counter-culture. I now feel the need to use the phrase ‘Beatnik horror’ in daily life.

— Aleisha Ward (@nzjazzhistory) September 2, 2015

The death yesterday (31 August 2015) of Edward, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu at the age of 88, reminded me of what a remarkable life he had, not least (perhaps surprisingly) in two key moments of festival culture in Britain. (The Guardian obituary fails to even mention the jazz festival, as one commenter—see below—not me btw…—points out.)

I wrote about these festival moments first in Andy Bennett’s 2004 collection Remembering Woodstock, and my own Circular Breathing from the following year, drawing on AHRB-funded archival research at Beaulieu, in particular the press cuttings files, as well as an interview with Montagu from 1999, and what follows is an extract from my Bennett essay. (The complete text, open access, is available here.)

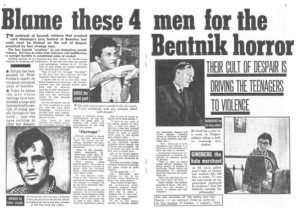

The near riot at the Beaulieu Jazz Festival on Saturday … was a disgraceful affair. There are those who criticise Africans and who say that such people will never be fit to govern themselves. But a tribal dance to the sound of a tom-tom has a more civilised air than this modern wreck and roll to the beat of the jazz drum.—Bradford Telegraph and Argus, 1 August 1960

… But the new romantic lifestyles, rural excursions and incursions, musics and fashions, temporary communities of festivals and marches, competing versions of Englishness and the past, that I am writing of and have linked as Beaulieu Jazz Festival (1956-61) and the Aldermaston Easter marches of CND, do not always behave. For peace is not always easy during carnival.

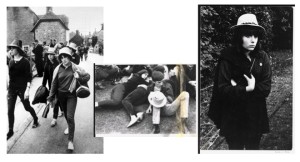

At the 1960 Beaulieu festival, the trad clarinettist and somehow pop star Acker Bilk entered on a Model T Ford, courtesy of the Motor Museum. By the end of Saturday night, vehicles had been targeted by festival-goers for destruction—I am resisting calling this an early anti-car protest, that is too utopian an argument even for me. While Acker played, jazdup youth climbed a scaffolding lighting rig, and removed horses from the roundabout stage and mounted them on rigging as they climbed. A storage shed was set alight, and a 1921 14-seater charabanc had its hood burned. Over the Saturday night riot 39 people were injured, none seriously, though two people were subsequently jailed for assaulting police officers. For George Melly, though, ‘[i]t wasn’t a vicious riot. It was stupid. The traddies in rave gear booing the [modern jazz Johnny] Dankworth Band. A young man climbing up the outside of the palace in the floodlights waving a bowler hat from the battlements. Cheers and scuffles’. Others viewed exuberant youth quite differently. Kenneth Allsop in the Daily Mail asked his readers:

Why do the Ravers rave? At which point do enthusiasm and high jinks twist into the urge to hate and destroy?… Whacky dress and wild fun do not necessarily spell delinquency. Yet for a certain product of our Affluent Society this seems to have become a rebel’s uniform of viciousness—and the degree is fine between beating-up a jazz festival and beating-up Negroes in Notting Hill and Jews in Germany. (1 August 1960)

For some of those activists and idealistic jazz fans who had been on the Aldermaston march a few months earlier it must have come as a surprise to be now compared to racists and fascists. But Allsop’s point is perhaps more a symptom of a common English unease with American popular culture (it was Teddy Boys, inflamed by the new sounds of rock ‘n’ roll, that beat up London’s black youth), or with unfamiliar mass events such as these new youth festivals. Montagu himself was to say that ‘You’d need a policeman in every garden’ in Beaulieu village if the festival was held again—hardly the image of pastoral promise to transmit.

Beaulieu in 1960 was important too because of it was an example of the mediation of subcultural panic. Jazz from the festival was filmed and broadcast live on BBC television, and on the BBC Light Programme radio network. During the riot on Saturday night, the live broadcast was cut by six minutes, an interruption prefaced by an anxious BBC live commentator saying: ‘Things are getting quite out of hand. [pause] It is obvious things cannot continue like this.’ A commandeered BBC microphone was used to broadcast a shout from one fan for ‘More beer for the workers!’

Beaulieu in 1960 was important too because of it was an example of the mediation of subcultural panic. Jazz from the festival was filmed and broadcast live on BBC television, and on the BBC Light Programme radio network. During the riot on Saturday night, the live broadcast was cut by six minutes, an interruption prefaced by an anxious BBC live commentator saying: ‘Things are getting quite out of hand. [pause] It is obvious things cannot continue like this.’ A commandeered BBC microphone was used to broadcast a shout from one fan for ‘More beer for the workers!’

An apologetic BBC spokesperson was quoted in the next morning’s press: ‘We have had a lot of telephone calls from viewers who thought the scenes were disgraceful’ (quoted in Sunday Express, 31 July 1960). On the other hand, the News of the World was happy to report to its readers that its switchboard had been jammed with calls from television viewers wanting to know what was happening (News of the World, 31 July 1960).

The ‘BEATNIK BEAT-UP’, as it was headlined in one newspaper, was reported in the Commonwealth and world press—in South Africa, the United States, Argentina, Gibraltar, Australia, Kenya, Canada, Italy, Germany, France. The combination of aristocracy and jazz madness was an outstanding popular story of English eccentricity run, literally, riot. The Battle of Beaulieu was in part a symptom of jazz purists’ investment in their particular form: subcultural tensions between traditional jazz fans and modernists were evident (‘Go home dirty bopper’ was by this stage a favoured slogan of tradders). We would do well here to remember that, as E. Taylor Atkins observes wryly, ‘[o]ur comfortable characterization of jazz as a “universal language” fails to do justice to the conflicts the music ignited around the world’. This may explain the irreparable damage inflicted on Acker Bilk’s banjoist’s instrument: the banjo was truly despised by modernists.

The riot was also a demonstration of the cumulative sense of empowerment the collective identities of groups attending the event each year developed with it—the carnival beginning to blur the distinction between participant and observer, as well as to challenge and invert the social hierarchy. Here the minor manifestations of transgression at the 1959 and 1961 festivals should be acknowledged too. Also important though was the presence of the media—the camera as inflaming device—and its privileged space at the 1960 event—the camera as intrusion. Jeremy Sandford notes this:

Montagu had been criticised for giving too much space to T.V. cameras, and of thinking too much of the T.V. technicians and too little of his audiences.… The BBC had also been accused of a prissy and somewhat condescending attitude ‘to unsafe things like Youth and Jazz’.

For Mick Farren too, the Beaulieu festivals were ‘primitive mini-Woodstocks that reached media attention when the audience took offence at being filmed as though they were sociological exhibits and turned over BBC TV cameras’.

[Click on the image below for some footage of a Pathé newsreel showing hip cats at the 1961 Beaulieu Jazz Festival… YOUTH HAS A FLING]

There is a (retrospectively) intriguing coda to the Beaulieu Jazz Festivals. For 1962, a Daily Mail article describes the extraordinary early invention of a proto free festival, of the kind organised extensively in Britain in the 1970s and early 1980s. This indicates the distance between festival organisers and festival-goers, and the increasing autonomy of carnival.

Like Frankenstein, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu has created a monster from which, it seems, there is no escape. After the beatnik riots last year Lord Montagu vowed: ‘There will never again be a jazz festival at Beaulieu’. But last night he told me that he has had to appeal to the police for protection from the jazz beatniks, who threaten to descend on the picturesque, Hampshire village again. Thousands of leaflets have been distributed in Chelsea exhorting the ‘trads’ and ‘moderns’ to turn up in force on August 4 ‘for a free rave to the bitter end’. The leaflets, signed ‘Pete the Brolly’, read: ‘If you can play any musical instrument please bring it with you and help make a successful weekend for every one. Spread the news and rave on’. (Daily Mail, 16 May 1962)

The uncertainty of this putative Beaulieu free festival’s countercultural or subcultural construction—it veers in its embryonic way between an alternative gathering or ‘free rave’ and a mods vs. rockers-style showdown between competing jazz fans ‘to the bitter end’—should not detract from its importance as an early manifestation of more radical DIY youth culture. It also provides evidence of the emotional and social investment the audiences at Beaulieu developed in making the festival their own over the years it ran, even to the extent of claiming it as their own autonomous event.

The newspaper returned to the story a month later, when the straight identity of white beatnik Pete the Brolly (complete with goatee beard and a small signifier of English eccentricity, a monocle, though no umbrella, I think) became clear at a court appearance following, of course, a drug bust. Outside a London court, following a £10 fine for possession of cannabis found during a raid on the candlelit Chelsea jazz club Café des Artistes, Pete the Brolly owned up: ‘I am the cat who has been distributing thousands of leaflets in Chelsea and throughout the country exhorting anyone who can play a musical instrument to come to an unofficial Beaulieu jazz festival on August 4’ (Daily Mail, 9 June 1962). Pete the Brolly, aka 30-year old Peter Dawson, said from his Holborn office, just visited by two police officers:

This is really awful man, but awful.… [The police] told me if I persisted with the plan I would be the first to be carried off. When I wrote to Lord Montagu I pointed out that to combat any trouble I would organise a beatnik police force. There would be little risk of damage. This rave would have lasted a while. We planned to live in the forest while it was on. (quoted in the Scottish Daily Mail, 16 June 1962)

Wild pastoral living, self-policing, DIY music-making, and a non-commercial economy—many of the ingredients of the free festival movement are glimpsed here up to a decade before its popularisation in Britain, and long before the inspiration of Woodstock. The poor or political in the free community of Desolation/Devastation Hill outside the fences of the 1970 Isle of Wight festival, the 1970 IT financial ‘fuck up’ (IT’s own description) that became the free festival of Phun City, the 1971 free festival of Glastonbury Fayre organised and financed by upper class drop-outs like Andrew Kerr and Arabella Churchill—these were the early manifestations.

But as an ideological social movement of sorts in Britain free festivals came into their own with Windsor People’s Free in 1972 and then the best known, Stonehenge Free, from 1974 on. In a way, with Pete the Brolly, Beaulieu was present at the lost beginning of the movement, and also at its notorious arrest, the ‘Battle of the Beanfield’ near Stonehenge, where the large convoy of New Travellers on its way to the stones for the 1985 festival was violently ambushed and broken up by police. As head of English Heritage then, Montagu was responsible for the preservation of national monuments like Stonehenge, though he was not absolutely opposed to some sort of gathering.

My desire was to turn the festival into some sort of controlled event, which meant it could still have happened. I would have loved to have made a sensible event—in fact, one year we offered 400 tickets to the alternative community to attend the stones during the solstice, but they said no, we’d rather stay outside. I did then think they were anarchists, you see: they’d rather riot really. Were there anarchists at Beaulieu, too, among the trad jazzers, beatniks, and CND-ers? Oh yes, quite possibly. (personal interview, 1999)

At Beaulieu in 1960 (and, in leaflet form at least, 1962), at Stonehenge after 1985, the aristocratic imperative to grant and control freedom of festival was challenged and rejected. As is its wont, carnival would not be so easily limited, it required its potential for social inversion to be fulfilled. And so it was—as the Daily Mail delineated the carnivalesque trajectory of the Beaulieu Jazz Festivals for its readers:

At first audiences were sprinkled with famous faces. Gerald Lascelles, cousin of the Queen, was one who made the trip to Beaulieu. Then the rowdies moved in and last August [sic: July] there were riots, nude bathing parties, fights with broken bottles, beatings-up of innocent bystanders and drunken orgies. Fifteen ambulances were called. ‘I was disgusted and flabbergasted by the drunken youths and girls lying on the ground’, said Lord Montagu. (Daily Mail, 16 May 1962)

(Perhaps audiences expected a degree of sexual licence such as they might have heard of reported from the etablishment-rocking scandal of the Montagu trials in 1953-54.) Just as in the Victorian Beaulieu Fairs banned by his grandfather, the transgressive purpose of carnival, in the highly encoded and hierarchical social setting of an English stately home, burst out with energy, without apology, once more. That the febrile Americanisms of jazz should now be carnival’s accompaniment, compounded the ‘disgust’, and/or the pleasure….