‘the first step that put me on the road to Rotten’—John Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten), talking about his childhood meningitis and hospitalisation

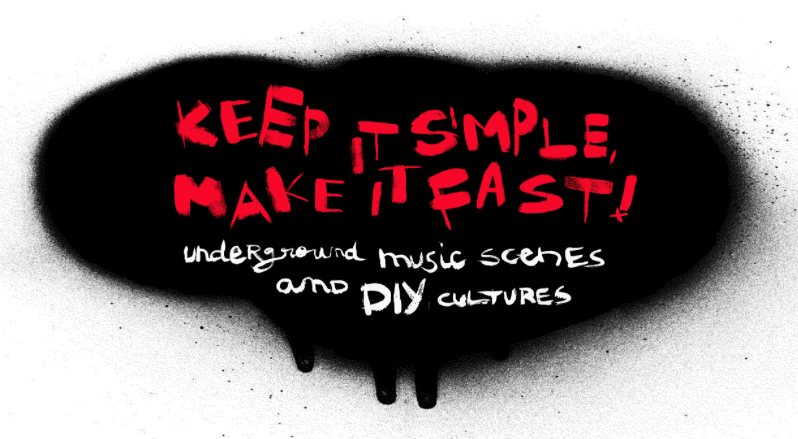

Giving a talk about this topic at MediaCityUK, University of Salford this week, part of our regular programme of research seminars. It’s a bit of a dry run for my keynote at the KISMIF conference in Portugal in July (see poster below). I’ve broken my old rule about not writing about punk rock (again)… It’s to do with a piece I’m writing for the Oxford Handbook of Popular Music and Disability. Here’s the abstract. The paper is on Wednesday 21 May, 3 pm, MediaCityUK. Do come if you’re in my area. (Every punk/Manc blog shd hv a Fall ref.) I probably won’t do all of below, might even just focus on the new reading of Johnny Rotten as crip, as suggested above in epigraph.

Giving a talk about this topic at MediaCityUK, University of Salford this week, part of our regular programme of research seminars. It’s a bit of a dry run for my keynote at the KISMIF conference in Portugal in July (see poster below). I’ve broken my old rule about not writing about punk rock (again)… It’s to do with a piece I’m writing for the Oxford Handbook of Popular Music and Disability. Here’s the abstract. The paper is on Wednesday 21 May, 3 pm, MediaCityUK. Do come if you’re in my area. (Every punk/Manc blog shd hv a Fall ref.) I probably won’t do all of below, might even just focus on the new reading of Johnny Rotten as crip, as suggested above in epigraph.

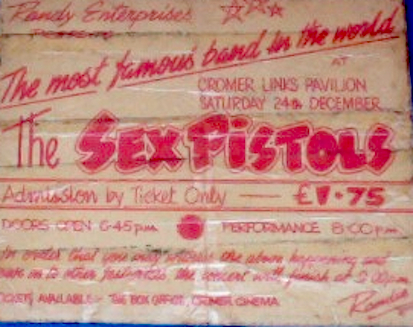

This essay is focused on (post)subculture and disability, and specifically on the popular musical subculture of punk rock. It considers the extent to which punk rock in the 1970s and after opened up a space in music for disabled performers and audience members. There are two main areas of discussion. First, questions of subculture and counterculture are explored, in terms of both cultural studies theory and of disability. How far has subculture and postsubculture theory included or even acknowledged the presence of disability? How can subcultural concerns such as clothes, style, fashion, media representations, enhance our understanding of the social significance of popular music for disabled people? Second is a focus on the original British punk scene of the late 1970s and three major artists, varyingly disabled, from it. These are Ian Dury, Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, and Ian Curtis of Joy Division. The essay concludes with a view of punk’s ‘cultural legacy’ in the disability arts movement, including the performance of Dury’s 1981 controversial protest single ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ at the 2012 Paralympics Games in London.

Ooh, this bit’s good, here’s an extracted para, gives a flavour:

Punk and punk-era band names have been characterised by a connotation or description of violence or aggression, sex and fetish, social turmoil and irruption, but also of the body, and in particular the disabled or disfigured body. So: the Blockheads, Deviants, Epileptics, Subhumans, Vital Disorders (UK), Disability Sickness, another Subhumans (both Canada), the Autistics (an early name of Talking Heads), Cripples, Disability, Screamers, Voidoids, Weirdos (USA), and many others. This mildly controversial and contumacious juvenilia signals an identification of misfit, clearly, on the part of band members, but also it contributes to the subcultural terrain of the scene in which both direct and indirect referencing of disability has been widely accepted. Such naming becomes self-fulfilling as a public signifier of music offered: I venture to suggest that a band called, say, the Fuckwit Mutants (I made them up, but would not mind seeing a short set) is unlikely to be playing disco, blues or country tunes. As for punk audiences, their anti-dancing style of the pogo (basically, jumping up and down, on or off the spot), while physically demanding, was a further display of a kind of incompetence, an inelegant if thoroughly energetic solo reaction of body to music. When dancing to slower pieces, or to punk’s own musical (br)other, reggae, one saw, one made, frequent ‘twitches of the head and hands or more extravagant lurches’ (Hebdige 1979, 109). (Indeed, could we say that what I have elsewhere written of as the alla zoppa stepfulness (McKay 2013, 197, n. 9) of reggae spoke powerfully to the cripness of punk? Does that offer another way of understanding the close relationship between the two?) The unhygienic and in wider society unacceptable leakiness of the gesture of ‘gobbing’ (spitting) at bands onstage enhanced and lubricated punk’s bodily excess.