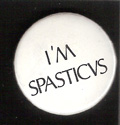

Surely this song should be no. 1? Originally Shakin’ All Over was to be called Spasticus. The 2010 AHRC award that helped fund its writing was indeed titled Spasticus: Popular Music & Disability. The badges/buttons above are themselves a small tribute to Dury, presented in the style of his famous set from 1977, sex& drugs& rock& roll&.

I write a good deal about Dury’s cripsongs. HALLO TO YOV OVT THERE IN NORMAL LAND.

English singer and lyricist Ian Dury was for a time in the UK in the post-punk years the highest profile disabled pop star, even reaching no. 1 in the charts in 1979 with the single ‘Hit me with your rhythm stick’. He contracted polio as a child, in a Southend swimming pool, in 1949. This was the same year folk/pop singer Donovan contracted the disease, in Glasgow (via a faulty vaccination—quite common), and US saxophonist Dave Liebman too. Here is some interview material I did with The Rotarian magazine about polio and popular music; Rotary International, alongside the Gates Foundation, still today runs a huge international campaign to rid the world entirely of polio.

Actually, there is an entire chapter, called ‘Crippled with nerves’ (title of an early Dury kind of love song), about polio and popular music.

‘Spasticus Autisticus’ is Dury’s controversial 1981 single. As a global consciousness-raising exercise, the United Nations declared 1981 the International Year of Disabled Persons. Recorded in the Bahamas the song, and the single ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ was Dury’s public response to a public gesture. In this song there is I think an extraordinarily powerful—not only within the context of the pop world—‘narrative of corporeal otherness … [presenting] the disabled figure’s potential for challeng[e]’, in Rosemarie Garland Thomson’s term.

In fact, his motivation for the song, and his understanding of his own position as a public figure of disability, were complex. One idea was to ‘get a band together who were either recruited from mental hospitals or recruited from really savagely disabled places’. Instead, he explained, he wrote a ‘war-cry’:

The Year of Our Disabled Lord 1981 I was getting lots of requests. I turned them all down. We had this thing called the ‘polio folio’, and we used to put them in there…. Instead I wrote this tune called ‘Spasticus Autisticus’. I said, I’m going to put a band down the road for the year of the disabled; I’ll be Spastic and they can be the Autistics. I have [my band named the] Blockheads and that means they’re autistic anyway.

As he notes, the politics of self-naming is evident in the flaunted stupidity of calling his backing band the Blockheads (after another of his song titles). One possible title for his first solo album, his 1977 breakthrough record, before choosing New Boots and Panties!! was The Mad Spastic. Of course, ‘Spasticus’ was also a cultural effort at what Brendan Gleeson has termed ‘the reappropriation and revalorisation by disabled people of abject terms for impairment’.

The single was partially banned by the BBC, because of fears it would offend. As his first single since leaving the independent Stiff Records for the major label Polydor, it was a provocative, or even perversely self-destructive, choice. In fact we can and should go further—to release it as a single (let alone that it was on a new label, and with a new band) was an extraordinary, and brave, if also frankly career-shattering move on Dury’s part. A Sly and Robbie-backed Jamaican dance-rhythm pop song about spastics, released as a single, with a political message and a powerful and discomforting accusation?

The press release accompanying the single contains a section entitled ‘No handicap’, and locates the song firmly within Dury’s childhood experience, in a section headed ‘About polio’ (Polydor 1981). Yet in other ways it is the song that most departs from polio and from Dury’s medical-musical autobiography towards a much more general and encompassing position—the song’s hero’s name is, after all, Spasticus Autisticus, and Dury had no personal experience of autism.

The press release accompanying the single contains a section entitled ‘No handicap’, and locates the song firmly within Dury’s childhood experience, in a section headed ‘About polio’ (Polydor 1981). Yet in other ways it is the song that most departs from polio and from Dury’s medical-musical autobiography towards a much more general and encompassing position—the song’s hero’s name is, after all, Spasticus Autisticus, and Dury had no personal experience of autism.

That most public of his songs about disability, ‘Spasticus Autisticus’, closes with a number of male and female, normal and impaired voices proclaiming each in turn ‘I’m Spasticus!’ I have argued that the song is directed outwards, to the inhabitants of Normal Land, as a piece of cultural advocacy. But it is also directed inwards, in its closing collective gesture of self-identification and -empowerment. To achieve both, in a single pop song, makes it in my view a compelling challenge to what Marc Shell, in his brilliant book Polio and Its Aftermath, has termed the ‘the paralysis of culture’ that surrounds polio survivors, makes it instead a culture from paralysis….

Lots more in the book, including about the song’s glorious rebirth at the 2012 Paralympics Opening Ceremony. I’ve also discussed that here. ‘Get up, get up, get up, get down, fall over!’