In my 2011 book Radical Gardening I included material about gardens and gardening and health and disability. I included here a little discussion of Humphry Repton, the Norwich schoolboy who became the hugely influential designer who coined the phrase ‘landscape gardening’, and whose bicentenary of death we mark this week.

A decade or so before he died in 1818, Repton was involved in a carriage accident which left him physically disabled, with restricted mobility, and using a wheelchair (or bathchair). In Radical Gardening I mused on the kind of impact this life-change could have on him, on his work, on garden design. I do need really to go back and do further work on the question, to produce a more solid and informed piece about Repton, disability and garden design. (Another Norfolk figure on my list is the multiply-disabled Burnham Thorpe lad Horatio Nelson. I want to crip Nelson and Repton alike, as we say in DS [Disability Studies].) But here is my brief discussion from Radical Gardening, which identifies five ways in which we can crip Repton.

In the context what academics of disability in society and culture have begun to term our dismodern world—acknowledging the increasing presence and visibility of disability (due to inclusive legislation, improved medical techniques, and ageing populations)—we should note the place of gardeners with disabilities in gardening history. The eighteenth and early nineteenth century garden designer Humphry Repton, one successor to Capability Brown and the designer responsible for the term ‘landscape gardening’, was himself physically disabled. As a result of an accident in 1811/13—when in his [late] gardening prime—Repton became a wheelchair (or ‘bath-chair’, in the language of the day) user. His mobility impairment influenced his thoughts about gardening, and in his new physical state he now ‘turned his mind energetically to the best kinds of gardening for people like himself.

He wanted his gardens and parks to be linked to the wider world, and when he suggested a prospect from a terrace he often included a lively scene of motion—“a busy scene of shipping”, a turnpike with its carts, a view across a city like Leeds’. In this way the mobility-restricted gardener could feel connected and stimulated, the person with a disability included not excluded from the continuing experience of social activity and engagement.

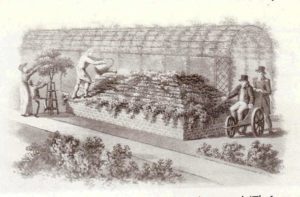

His 1816 The Luxury of Gardens includes an image which shows Repton in his wheelchair in a garden, directing works. Here the level of design displays some of the thoughtful elements enabling people with disabilities, in this instance wheelchair users, to be, or to continue to be, gardeners. The impact would be all the greater since Repton himself, as noted, a man at this stage of his life with restricted mobility, was a famous, professional gardener—and writer of a book the illustrations in which displayed rather than obscured his disability.

The raised bed is the primary feature, providing ease of viewing and enjoyment of the plants, as well as facilitating the act of planting itself, but there are other inclusive design features: the smooth and level path, the wide pergola, each of which would enable a wheelchair user to have ease of access around the garden, for instance.