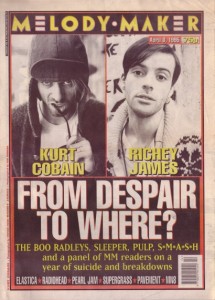

With the 20th anniversary of the death by suicide of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain, I’ve been thinking about pop and rock’s capacity to self-harm, to disable its own. I write about what I’ve called this ‘destructive economy’ in Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability. Here’s an extract from chapter 5.

________________________________________

… It is apparent that there are [music] industry-specific conditions, which tend to target certain kinds of pop workers: singers—frontmen and women—appear most vulnerable. Why the singers? Perhaps because there is arguably a closer relation between their instrument, which is the voice, and the body; perhaps because they are the focus in the band of fans’ attention, and feel the adulation and pressure more; perhaps because the singer is often also the lyricist, who writes the band’s subjective and expressive text….

… It is apparent that there are [music] industry-specific conditions, which tend to target certain kinds of pop workers: singers—frontmen and women—appear most vulnerable. Why the singers? Perhaps because there is arguably a closer relation between their instrument, which is the voice, and the body; perhaps because they are the focus in the band of fans’ attention, and feel the adulation and pressure more; perhaps because the singer is often also the lyricist, who writes the band’s subjective and expressive text….

Pop stardom is an illness that can seriously, even fatally, threaten health and undermine ability; to do well in this career is frequently to be or to get a bit or a lot fucked up. Its workers employ medical terminology to express the condition. His then manager described the unattractive transformation of Ian Dury, following the chart-topping success of the single ‘Hit me with your rhythm stick’ in 1979, as the result of him suffering ‘a very bad attack of number one-itis’. Shortly afterwards Dury himself wrote a song called ‘Delusions of grandeur’ in which he sang of the egotistical pleasures and symptoms of the career—‘I’m a dedicated follower of my own success … I’ve got megalomania’—as well as of the insecurities—‘Oh, look at me, just another pathetic pop star’. When a band member congratulated him on the astute self-confessional lyric Dury, extraordinarily, vehemently denied the song was about him, arguing that it drew on what he had observed in others. He did though himself say, of the industry’s traditional trajectory to success and beyond (usually back), ‘after people make it, a malaise sets in’.

Deborah Curtis notes that, round the same time (the punk scene had inscribed within it a self-referential narrative about its own relationship with the industry, a symptom of its political unease with its own commercial imperatives), as Joy Division became more successful in late 1970s Britain, her husband and that band’s frontman ‘Ian [Curtis] contracted what was known as LSS (Lead Singer Syndrome)’. Number one-itis and LSS are the medical metaphors that describe the industry’s sheer damagability, which may be focused most on, but is not restricted to, those who make it.

The pop and rock industry has a notable capacity to facilitate the ruination of its workers; it’s a high-risk, hi-vis workplace culture where one is never quite safe. And, extraordinarily, it seems where there is never quite enough trust to go round. This feature is a neglected area of research in popular music studies. Consider the kings of the scene, the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Elvis Presley (died 1977), and the King of Pop, Michael Jackson (died 2009), whose own controversial physicians prescribed the fragile men in their care huge amounts of drugs in the periods leading up to their deaths. Dr Feelbad. Pop’s unsettling medicine is a repeat prescription, a systemic regicide for the subjects to follow….