About a decade ago, the music writer George Berger contacted me for an interview as he was gathering material for a book on the influential 1970s/1980s British anarcho-punk band/collective Crass. He followed up with transcriptions of the material he wanted to use from the interview, for me to check and amend if necessary. (Good. Just what I do myself.) I found that old transcription today. Here it is, below. I am currently writing a foreword for a new anthology of critical writings about anarcho-punk, so that band, that period are in my mind. Berger’s book came out as The Story of Crass in 2006.

“That was great”, notes Professor George McKay of the Asylum record, “it was quite difficult for music to shock in the middle of punk, but that one did.”

GEORGE McKAY ON THATCHER, LEFT WING / RIGHT WING YOU CAN STUFF THE LOT

GEORGE McKAY ON THATCHER, LEFT WING / RIGHT WING YOU CAN STUFF THE LOT

“If you espouse something that’s outside the parliamentary framework, the theory goes that that framework then shouldn’t really have an impact on you, because that’s not your agenda. It seemed to me that anarchism was always most interesting when its advocates were right outside, because they could say things that no-one else would dare to say.”

McKay cites the example of the green grass mohican put on the statue of Winston Churchill ‘nearly everyone was outraged—or felt the need to be seen to be expressing outrage—except anarchists. It was primarily anarchists who were asking some of the more awkward and maybe profound questions (about Churchill and his background, the imperial legacy of military adventure, rather than simply the anti-fascist struggle). They could only do that because they didn’t have anyone to answer to, or even a reputation to uphold.’

“It was still relatively possible back then to find alternative spaces that took you outside established left-wing politics, whether revolutionary or parliamentary, but then also allowed you to turn your back on the right-wing.”

“I don’t know if it would have been any different if a few hundred anarchists had thrown themselves into the fight. I don’t know if that’s really what they were there for. To an extent theirs was a different oppositional role—to maintain a critique of, in Crass terms, the whole system, its history, values and structures”

CND

George McKay: “Around that time, there is a number of different music contributions to the movement. One of the big ones was Glastonbury Festival. From 1981, Glastonbury was organized through National CND offices – through CND’s national structure and organisation – and that’s one of the key reasons why Glastonbury became successful… remember, there were only three Glastonbury festivals held during the seventies, and the one that most resembled what it became, the 1979 event, a fundraiser for the UN Year of the Child, was something of a financial disaster. Over the eighties, the usual figure quoted is that Glastonbury gave CND something like a million pounds, and that really helped support things.”

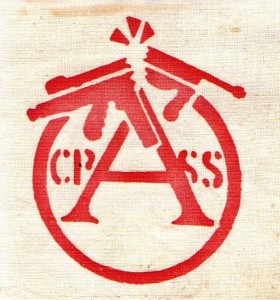

George McKay: “Because Crass bolted the CND symbol onto the anarchy symbol, they made that connection more explicit. But there were a lot of other things going on too – in November 1983, there were 102 peace camps up and down the country, inspired by Greenham Common women, for instance. Crass had a role to play, but I don’t know I’d want to overstate it.”

THE FALKLANDS WAR

George McKay: “There was something of an eschatological imperative in the air at the time, this sense of doom, ending, nuclear eschatology. That was all there in the zeitgeist.”

(PUT PETE WRIGHT QUOTE IN HERE)

“It struck me as the confirmation of everything that they feared – that we were now slipping over. There was a grand conspiratorial side of Crass – the system will get you, everything was the system… but in that moment the state was mobilized and the army went out and killed people, and got killed. Young men. I don’t think they made too much of it – I thought Crass understood how important it was for the British establishment to have a victorious war. Maybe the difficulty they had was in transmitting an adequate level of outrage, of upping the level of what they called their ‘aesthetic of anger’ to take into account this new moment of destruction and nationalism”

ON 10 NOTES…

George McKay is equally forthright in his opinions on the piece: “To be honest, I thought it was just crap. When they tried to be positive, utopian even, it just wasn’t as powerful.”

ON CRASS

“They didn’t strike me as being an individualizing or bourgeois event. If you look at it from a purely consumerist perspective, the fact they played benefits and played all these grassroots little places… all the events spoke to me of a project to do something a bit different.”