Having spent much of the past 4-5 years writing Shakin’ All Over, a book about popular music and disability, that includes a chapter on hearing impairment and rock’s culture of damage, I was struck by today’s front page story in the Daily Mirror, which tells of rock star Chris Martin’s experience of tinnitus. As the paper puts it, ‘The seven-time Grammy winner was warned by doctors that the debilitating ringing in his ears – coupled with splitting headaches – could end his stellar music career.’

Having spent much of the past 4-5 years writing Shakin’ All Over, a book about popular music and disability, that includes a chapter on hearing impairment and rock’s culture of damage, I was struck by today’s front page story in the Daily Mirror, which tells of rock star Chris Martin’s experience of tinnitus. As the paper puts it, ‘The seven-time Grammy winner was warned by doctors that the debilitating ringing in his ears – coupled with splitting headaches – could end his stellar music career.’

We should remember here the plaintive and ironic comment by Who guitarist Pete Townshend, from 2006, talking about his own hearing impairment: ‘I have unwittingly helped to invent and refine a type of music that makes its principal proponents deaf’. The Who were once (in 1976) named ‘The Loudest Band In the World’, of course.

Extreme volume is part of the rock aesthetic. From a quick scan among my old albums and singles, I was reminded that the back cover of David Bowie’s 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars contains the instruction TO BE PLAYED AT MAXIMUM VOLUME, for example. The contemporary English experimental rock band My Bloody Valentine were notorious for employing loud volumes in live performances; their reunion concerts in 2008 and 2009 were noteworthy for the controversy around the extreme loudness, with earplugs on offer at the doors and some audience members leaving because they felt ‘physically distressed’ by the noise. Bandleader Kevin Shields (who himself has tinnitus) has defended the band’s sonic aesthetic—which include trying to induce a state of physical unbalance or disorientation via the volume and frequency of the sounds produced—but also acknowledged the difficulty.

We play with low frequencies that are nothing like anyone has ever heard before—it’s a chaos that sets off a kind of inbuilt alarm system…. We’d like to say that it is cool to wear earplugs; it’s not cool to get your hearing damaged. And anyway, feeling the music is a great experience.

Over the past few years there has been a slew of journalistic and academic articles about, as one put it, ‘music making fans deaf’, and musicians. These writings have been prompted by the hearing loss experiences of the ageing rock generation combined with new concerns about young people’s encounters with loudness via personal stereos. Writing in Rolling Stone in 2005, Jonathan Ringen mapped out the affected male generation: ‘[i]n 1989, Pete Townshend admitted that he had sustained “very severe hearing damage”. Since then, Neil Young, Beatles producer George Martin, Sting, Ted Nugent, [Fleetwood Mac drummer Mick Fleetwood] and Jeff Beck have all discussed their hearing problems’. An advice booklet produced by a campaign group called Hearing Education and Awareness for Rockers (yes, that’s HEAR) quotes the following statistic: ‘60% of inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame are hearing impaired’.

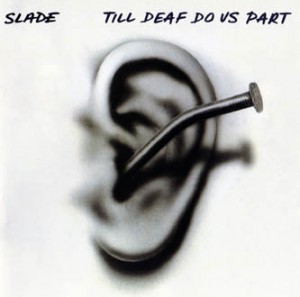

In rock, then, loudness is part of the package: this is seen clearly in album titles like Nazareth’s Loud ‘N’ Proud (2010) and Ozzy Osbourne’s Live & Loud (1993), or song titles such as Kiss’s ‘I love it loud’ and ‘Shout it out loud’ (available on the album Sonic Boom). The career of British glam rocker chart-toppers Slade exemplifies the aesthetic: their 1970 album, their first with the name Slade, is called Play It Loud, their final album in 1987 You Boyz Make Big Noize. The first of their three singles to enter the British charts at no. 1 was ‘Cum on feel the noize’ (1973), later covered by Quiet Riot and by Oasis; intriguingly the effect of the group’s characteristic mis-spelling of song titles works only in, in Lennard J. Davis’s term, deafened mode. But it is Slade’s 1981 album Till Deaf Do Us Part, their most heavy rock- rather than pop-oriented record, which is particularly notable. Guitarist Dave Hill claimed responsibility for the album title, explaining the perverse thought behind the ‘twist on words’: ‘What would separate you from your fans, what would it be if they went deaf?’ Hmm…

In rock, then, loudness is part of the package: this is seen clearly in album titles like Nazareth’s Loud ‘N’ Proud (2010) and Ozzy Osbourne’s Live & Loud (1993), or song titles such as Kiss’s ‘I love it loud’ and ‘Shout it out loud’ (available on the album Sonic Boom). The career of British glam rocker chart-toppers Slade exemplifies the aesthetic: their 1970 album, their first with the name Slade, is called Play It Loud, their final album in 1987 You Boyz Make Big Noize. The first of their three singles to enter the British charts at no. 1 was ‘Cum on feel the noize’ (1973), later covered by Quiet Riot and by Oasis; intriguingly the effect of the group’s characteristic mis-spelling of song titles works only in, in Lennard J. Davis’s term, deafened mode. But it is Slade’s 1981 album Till Deaf Do Us Part, their most heavy rock- rather than pop-oriented record, which is particularly notable. Guitarist Dave Hill claimed responsibility for the album title, explaining the perverse thought behind the ‘twist on words’: ‘What would separate you from your fans, what would it be if they went deaf?’ Hmm…

Postscript. Other recent stories have featured musicians’ and music workers’ experiences of music-induced hearing impairment, including: