There’s a nice feature in the Independent online today, by Kashmira Gander, ‘Why gardening is more political than ever’, linked to the Chelsea Flower Show 2016, and specifically the modern slavery garden of designer Juliet Sergeant. You can read Kashmira’s piece here.

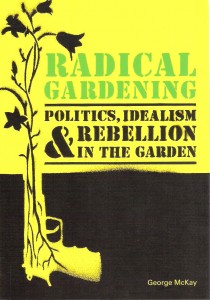

Here are more fully my responses to her questions as she was researching the article late last week. They draw of course on my work in Radical Gardening.

Here are more fully my responses to her questions as she was researching the article late last week. They draw of course on my work in Radical Gardening.

Do you think gardening is a political act, if so/not why?

There are lots of ways to think of a politics in gardening. The domestic garden is your own small green patch of earth—there’s a deep micro-politics in just how you exactly you treat that, I’d say. Organic or chemical? Lawn or veg patch? Private garden, allotment, community garden or guerrilla garden? I read one book that called the lawn ‘a totalitarian regime’—that made me think! And what about invasive species, immigrant plants coming over here, etc etc. Nationalism and planting have awkward complex roots too: the Nazis fetishized the land, many were committed organicists and biodynamicists in their planting, while even a few years ago the BNP were calling on gardeners to plant good British varieties of heritage fruit trees, to protect British tradition in the garden.

What is significant of gardening and its link to the ownership of land (or not, in the case of allotments).

Thinking of allotments for a moment, I made the case in my book that allotments are a profoundly anti-capitalist thing. I was trying a provocation, trying to see the allotment as something different from the familiar imagery of a rickety shed or a marrow-growing competition. But think about it: the rents charged by your council for a plot are really very small, and often bear little relation to the actual land value as, say, developers might see it. That’s a wonderfully wilful rejection of commercial property value right there. Second, what do you do with your produce in the summer, when you are a lucky or skilled enough allotmenteer to have a glut of vegetables? You give it away! Actually, often you have to give it away, because your allotment by-laws forbid you selling it for profit. So, again, the cosy hotch-potch bee-busy DIY dirty green space of the allotment is actually a hotbed of anti-capitalist gift economy!

What do you think that gardens are symbols of the establishment, particularly in the UK?

What do you think that gardens are symbols of the establishment, particularly in the UK?

I remember reading a book called The Squatters’ Handbook a few years ago, a how-to manual about squatting, published by a radical press. There was a line in it that stuck with me: ‘Land is what it’s all about’, and I used that line in my book Radical Gardening. It’s an obvious thing to say, but one made potent by the context of squatting, which was an action that challenged property and ownership. The idea of the establishment garden—presumably you’re thinking of a stately home, a country estate, a place of history and hundreds of acres, class and privilege, that many Britons love to visit at weekends. Such gardens, extensive and expensive, are displays of wealth and tradition. Actually, I like them too—and I also see them as political spaces.

Leading on from the above, do you think gardening is more political if a woman or someone from an ethnic minority is doing it?

Any activity that’s been seen as exclusive, that some people are not allowed in to or have to felt welcome at, is political by that act of exclusion. If the excluded start to challenge and change their absence, that’s a political act of sorts. Why should the garden be the exception here?

What do you think of the idea that gardening is man’s way of exerting control over nature, in a similar way to pheasant shooting and blood sports?

The garden is a growing, nurturing space, not a killing one: the point is to make something grow, often at a pace that is slow for contemporary society. Plant some perennial flowers and you are kind of investing in the future, because you are not going to see a display for one or two seasons. Put a couple of pear trees in your green patch and you are really looking 20-30 years ahead. These are acts of faith in a future world, aren’t they?

Can gardens be political in the same way that vegetarianism is?

But they are connected! Vegetarians think about the food on their plates, gardeners grow the food on their plates. I met so many people in the course of writing Radical Gardening who were keen gardeners, interested in organic production, or guerrilla gardening, slow culture, allotments, anti-GM politics, or were seed-swappers, etc etc, who were also vegetarians or vegans. These didn’t seem in any way separate, but in fact profoundly linked.

In what other ways can gardens be important? E.g. memorials.

Of course gardens also have a very powerful role in the process or ritual of memorialisation—in fact, we can say that flowers and planting are a key part of that. You can see it in the symbol of the red poppy each November, as well as in the small gardens that are war memorials in every village up and down the land: a stone memorial, a plinth, a neatly-trimmed lawn, a small bed of flowers, often a chain around the space to frame the whole. I have been interested too though in the dialogue the peace movement has set up via gardens and floriculture: the white (rather than red) poppy of the Peace Pledge Union, the ‘peace garden’ movement as part of the 1980s anti-nuclear campaign. Left-wing local authorities made ‘peace gardens’ in public parks, with Japanese-style planting and architecture to indicate solidarity with the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Here we can see a very clear instance of garden and activism linked together.

What is the most important thing about gardening that readers should know about?

Readers should think about this quotation from the contumacious artist-gardener Ian Hamilton Finlay, who gardened at Little Sparta in the Scottish borders: ‘Certain gardens are described as retreats when they are really attacks’. As we academics say: Discuss.