Reviews and media interest in the book and the work was quite widespread on publication, and positive citations continue to appear across disability studies and popular music studies. Here are extracts from, and links to, reviews, press mentions, citations, etc….

Cultural Disability Studies in Education

The sole entry in this section: ‘Highly recommended reading (Disability Studies and Popular Music Studies): McKay, G. Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability‘. (David Bolt 2019, 83)

‘It was not until the 21st century that the journal Popular Music formalised a relationship with disability studies via a special issue that recognised that the “uncontrollability of the pop body has been a persistent feature since its early days” (McKay 2009)…. Indeed, when popular music studies and disability studies are so combined the normative divide becomes apparent and thus problematised on many levels’. (Bolt 2019, 74)

Annals of Human Sciences vol . 42

It is five years since this book was published, discussions haven’t be made especially in Japan as far as I know. Indeed some disability culture have strong connection with music historically. For example the Japanese instrument Biwa has been played by blind people for 1000 years…. Therefore it is meaningful to introduce this book to Japan, where popular music is mainstream nowadays…. [T]his book gives new and important suggestions for beginning a new discussion in both academic and non-academic fields. (Sachi Masai, 2021, 65-66)

Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies

George McKay has written an accessible and illuminating book that will be of interest to disability and popular music scholars alike … [which] can claim to be the first monograph study of the intersection of popular music and disability.…

[The] introduction … carefully and explicitly locates the book within the field of disability studies…. McKay evinces a light touch with theory. He uses it deftly to illuminate possibilities for “cripping” pop music theory, without labouring points or over-abstracting the analysis. He provides a cultural, rather than musicological, account although there are brief passages of very close examination of how the semiotic modes of voice, music, lyrics, gesture, and movement combine to construct, perform, and also sometimes to conceal disability. In fact, McKay draws attention to a number of apparent paradoxes: the way the music industry both hides and flaunts disability, provides a simultaneously enabling and disabling site of cultural production, creates disability, and also campaigns on disability issues (including those it helps to create). (Owen Barden, April 2015)

Ethnomusicology Review

The first monograph-length study of disability in popular music, George McKay’s book is a welcome and timely contribution to the burgeoning body of scholarship on music and disability…. McKay considers musicians whose performance and reception has been indelibly shaped by disability and necessarily mediated through other positions of identity and marginality. At times he draws the reader’s attention to unexpected places, recasting familiar figures through the lens of disability (e.g. Neil Young), and also presenting characters that have nearly faded into obscurity because of their disabilities (e.g. Johnnie Ray). While he thoroughly investigates the many ways pop/rock can empower disabled musicians, he simultaneously contemplates the industry’s disabling capacities…. His musical readings strike an excellent balance between the formal and extra-musical dimensions of his chosen texts such that the book is accessible to a general humanities audience. Similarly, the book is available to those unfamiliar with disability studies since the author effectively primes the reader on important theoretical concepts in the field. McKay’s lifelong journey with disability beautifully informs the writing of his book; it is through his love of pop music and his crip rock icons that he first came to understand and ultimately embrace his own disability.

[Shakin’ All Over contains] an especially compelling discussion on a nearly forgotten musical great: deaf singer-songwriter and jazz pianist Johnnie Ray (aka. “the scrawny white queer with the gizmo stuck in his ear”). McKay demonstrates that Ray’s “stylized speech disfluency” (i.e. sobbing, stuttering, speech slurring, emphatic consonants, delayed/drawn out entries, etc.) and manic physical gestures (i.e. banging on the piano while standing, falling to the floor, etc.), both integral to the singer’s signature heightened emotional display, was an authentic performance of his deafness where staying in tune and in time as well as remaining physically balanced was a significant challenge for Ray, even with the use of his hearing aid. McKay also persuasively argues that the emotional vulnerability of the singer’s performances further exacerbated the insidious speculation about the depravity of his bisexuality and likewise feminized his disability.

McKay’s book covers an expansive selection of artists from across several decades and makes significant strides forward in our understanding of disability’s multi-faceted role in pop music…. Ultimately, McKay’s book is a compelling and vital complement to recent work on music and disability that has centered on Western art music. In revealing further avenues for critical exploration, the book will undoubtedly influence future developments in the scholarship on music and disability. (Jessica A. Holmes, March 25 2015)

Journal of Disability and Society

George McKay’s Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability is important not only because it is the first monograph to deal exclusively with the topic, but also because it provides foundational work across a wide range of concerns and approaches. While its individual chapters will function as springboards for many rich investigations, the book’s broad perspective illustrates the potential scholarly richness and epistemological rewards of the intersection between disability studies and popular musicology. (Laurie Stras, 2015)

Disability and Popular Culture: Focusing Passion, Creating Community and Expressing Defiance

… it is George McKay’s recent monograph Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability that provides the first comprehensive examination of disability in popular music from a post-social and cultural model of disability. McKay argues that disability is foundational to popular music and makes the observation that disability and the popular music industry emerged at the same time. McKay links the social construction of disability with the emergence of the concept of normal during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and historicises disability’s influence on popular music in relation to modernity, the mass media and popular culture. (Katie Ellis, 2015, Ashgate, p. 102)

Popular Music

Popular Music

[G]round-breaking….

[In 2008] McKay gave a much acclaimed and remembered lecture based on his extensive work on Ian Dury in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, which forms the basis of the book’s opening chapter, ‘Crippled with Nerves’, dovetailing Dury with Neil Young and Steve Harley, all polio survivors….

One of the most potent aspects of this book is … that … it forces the reader into an awareness of the prominence of disability in music, along with its near-invisibility in the music industry. Joni Mitchell, for example, was someone I had never associated with being a polio survivor, and … awareness of the widespread ‘cripping’ of popular music, as McKay calls it, is not something usually dwelt on. McKay includes welcome case studies of Robert Wyatt and Ian Curtis, and also ventures into areas not usually associated with disability studies – the deafening aspects of contemporary music volume, and the disabling effects of the music industry….

Promising us an ‘upbeat’ ending, McKay reveals he himself has Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, or ‘progressive muscular dystrophy’ (p. 193), before sharing with us a surprising epiphany he experiences at a Stevie Wonder concert in Manchester, which convinces him conclusively that ‘the world still needs shaking up’.

This important book also includes an impressive number of photos, many from the author’s own collection. (Tony Mitchell, vol 34:1 (January 2015), 164-166)

Golden Room vol. 32

‘Curl up with a great CD: “Spasticus Autisticus”‘

This month, we want to pay homage to one artist, whose personal protest sung was deemed too uncomfortable for mass consumption by an ill-informed, and arguably uncomfortable, political and music industry establishment. (14 September 2014)

Forbes

Most rock and pop stars are youthful, attractive, and healthy. But themes of illness permeate rock music. Bodies move uncontrollably. “Well, my hands are shaky and my knees are weak, I can’t seem to stand on my own two feet,” sang Elvis. “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” chimed in Jerry Lee Lewis. Sure, they’re talking about lust, dancing, and sexual ecstasy…. But it’s on the edge of normal. It’s about losing control, which is why it made so many parents uncomfortable. Early rockers and, subsequently, punk rockers, celebrated the freaky, the deviant, the damaged….

Able-bodied musicians have also used illness and disability to explore rock n’ roll themes of pain and disenchantment. The Who stuttered in “My Generation” (“People try to put us d-d-down”). Morrissey sang “Heaven Known I’m Miserable Now” on British television wearing a hearing aid and National Health Services glasses. Singers from Dylan onward sang with damaged voices. Through tattoos musicians use the body, and its painful and purposeful alteration, to express rock n’ roll values. “There are identifiable and powerful links between popular music and the damaged, imperfect, deviant, extraordinary body or voice, which can be, and surprisingly often is, a disabled body or voice,” wrote professor of Cultural Studies George McKay in his book on popular music and disability, Shakin’ All Over…. (Ruth Blatt, ‘What do Neil Young, Kurt Cobain and other disabled rockers teach us about working with disability and chronic illness?’ 29 July 2014)

Popular Music and Society

Despite the long interest in the body politics of popular culture, scholars have only recently begun to address the specific connections between disability and pop-cultural practices. George McKay’s astounding Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability is a crucial and compelling addition to this burgeoning literature. Brilliantly wrought and engagingly presented, Shakin’ All Over offers a rich basis for understanding these clear yet often misunderstood relationships. “There are identifiable and powerful links between popular music and the damaged, imperfect, deviant, extraordinary body or voice,” McKay correctly asserts, but “these links have been overlooked in much critical writing about popular music” (1). Shakin’ All Over corrects this scholarly deficiency in provocative and profound ways.

In a brisk 194 pages, McKay covers a stunningly variegated soundscape. Each chapter possesses unique strengths…. McKay’s chapter on hearing stands as a top-flight example of cultural criticism….

Throughout the book McKay balances sophisticated analysis with an engaging writing style. Shakin’ All Over is passionate, humorous, and sometimes profane, a rare academic work that is as entertaining as it is thought-provoking…

This astonishing work should inspire further examinations [of disabled pop artists]…. Perhaps the greatest strength of Shakin’ All Over is that it demands further scholarship. It is a brash, brilliant, and fist-pumping book that will inspire and entertain audiences for years to come. (Charles L. Hughes, 5 June 2014)

Review of Disability Studies

Review of Disability Studies

When I opened Shakin’ All Over I had no idea how much I would learn. Immersed in the book, I continually found myself looking up musicians I had not heard about, like Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel; Kevin Coyne and Kata Kolbert; Joy Division and the Epileptics; and ones I thought I knew a lot about, but did not realize they had a disability connection, such as Judy Collins, Donovan, and Dinah Shore.

McKay manages to discuss all of the above musicians and many more, while surprisingly (to him as much, or more, than to readers), disclosing his own disability and what he has learned about it in the process of writing this book. He deftly analyzes how disability fits in and influences popular music….

This is an academic book about popular music and disability from a professor of cultural studies, who is also a musician and, as we find out throughout the book, a person recognizing his own disability and his personal and professional life are more intertwined than he realised….

McKay ends the book, surprised to be attending and enjoying a Stevie Wonder concert, since he is usually more interested in lesser know performers in smaller venues. But he finds Wonder to demand disability access and awareness, “delivered onstage by the disabled musician at the pop concert, and the way that that utterance had been so cheered by everyone that powerfully struck me. The shakin’s not all over is it? The world still needs shaking up” (p. 194).

Throughout the book, McKay also incorporates many authors of disability studies into his analyses, including Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Petra Kuppers, Alex Lubet, Joseph Straus, David Mitchell, and Sharon Snyder, among many others. The integration of disability studies analysis with a cultural studies perspective is one of the many gifts of this book, which I want in my own disability studies and culture library and which will hopefully be in many other libraries and used in many disability, cultural, and music studies courses. (Steven E. Brown, RDS 10:1&2, 110-112)

10 best books or articles about disability history?

Art Beyond Sight is developing curricula for museum studies programs about disability and inclusion in museums. We would appreciate suggestions of the top ten resources (books or articles) that you would give to museum curators that might inspire them to become engaged in disability history.

The list produced includes Shakin’ All Over. (Sall Yerkovich, April 4 2014)

EMPRES Edinburgh Music Psychology Research

But seriously: how many Universities offer – as standard – a music degree curriculum which acknowledges and welcomes different types of physical ability? More interesting reading on the topic:

- Howe (2010). ‘Paul Wittgenstein and the Performance Of Disability.’ The Journal of Musicology, 27(2): 135-180

- Rose and Meyer (2000). ‘The Future Is in the Margins: The Role of Technology and Disability in Educational Reform.’ White Paper prepared for US Department of Education Office of Educational Technology. (http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED451624.pdf)

- Mackay (2013). Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability. Corporealities: Discourses of Disability series. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. (Nikki Moran, 16 May 2014)

Music and Disability at the SMT and AMS

George McKay, Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Salford, UK, since 2005, and founder of the CCM Research Centre [there], is the author of a recent book on music and disability, Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (University of Michigan Press, 2013). The following guest post by Professor McKay is a discussion of the themes and topics discussed in the book, which are relevant to studies of music and disability, especially those of popular music and culture.

Official Blog of Music and Disability Studies at the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory. (5 February 2014)

Times Higher Education

Times Higher Education

George McKay’s critique of the disabling nature of the music industry gives valuable insight into the counter-cultural commodification of marginalised experiences of embodiment.

This is the first monograph to consider Western popular music and disability. In revisiting artists such as Ian Dury, Neil Young, Teddy Pendergrass and Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, McKay examines disability as a source of cultural capital in the music industry and offers a critique of the industry for being disabling. As a disability studies scholar who has published on popular music, I see the need for books such as this. I also see the bravery in McKay’s self-reflective approach to writing as a disabled man and a music fan….

Shakin’ All Over is a first for the field and will be of use to those working in the creative industries, disability studies, music history and popular music. (Anna Hickey-Moody, 30 January, 2014)

All About Jazz

All About Jazz

… In five lucid, thought-provoking chapters McKay explores the common cultural and social territory of popular music and disability, inviting us to reconsider how music is mediated, manipulated and packaged for public consumption…. In the process, the author challenges our understanding of an important and ubiquitous aspect of mass culture usually taken for granted (the entertainment industry) and illustrates convincingly how popular music can ‘resound’ disability studies.…

Thoroughly researched and engagingly written, McKay’s illuminating cultural history of disability in popular music succeeds on another level as an important document of disability advocacy. If the majority of people in ‘normal land’ are, to quote Dury again, simply the ‘temporarily able bodied,’ then books like this assume an importance that goes far beyond the confines of popular music. As it is, songs like Neil Young’s ‘Mr. Soul’ (epilepsy) or ‘Helpless’ (polio) and Dury’s ‘Dance of The Screamers’ (disability) will never sound the same again. (Ian Patterson, 19 January 2014)

All Together Now

‘Pop go the myths about disabled musicians’. Article in disability magazine. (19 December 2013)

SalfordOnline

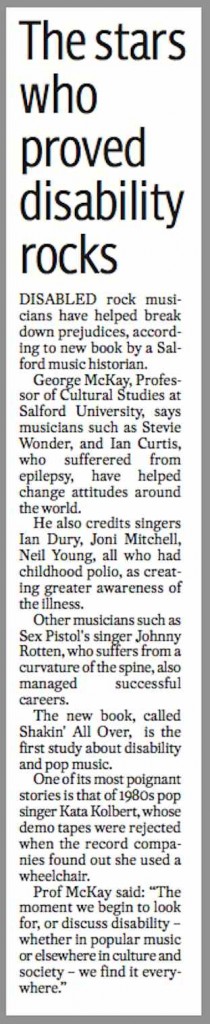

Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability, by Professor George McKay, seeks to dispel the perception that musicians must meet certain aesthetic ideals to succeed in the business. He discusses how disability influenced the careers of artists across a broad range of genres, including the Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten, Ian Curtis of Joy Division, The Who’s Pete Townshend, along with soul music’s Stevie Wonder….

An acclaimed author of many books on alternative cultures, festivals, and music from jazz to punk and rave, Professor McKay first became interested the history of disability in music 35 years ago when he saw Ian Dury perform live on the punk rock circuit. He began to wonder how many disabled artists have made a significant impact in popular music.

He said: ‘Dury walked on stage uncertainly, his body looked curious – we knew he was disabled because of childhood polio, but I don’t think we were prepared for the impact of his presence, his attitude, let alone his uncompromising songs about disability. The moment we begin to look for, or discuss disability – whether in popular music or elsewhere in culture and society – we find it everywhere.’ (‘Disabled musicians “everywhere”, says Salford professor’, 18 December)

Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry and Literature

Being the first to publish in a new field is always a double-edged proposition. On the one hand, you establish yourself as a pioneer and those who follow have to acknowledge and come to terms with your work. On the negative side, those who have learned from your experience, have the opportunity to make a sieve of your work and ask why you did not anticipate al those points that are so obvious to them. This is no less true in the field of disability studies than any other.

In Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability (University of Michigan Press, 2013), George McKay … tries to do something comparable with music genre that those in the Baby Boomer generation are most familiar with…. McKay sets himself a huge task... McKay largely succeeds in this….

The book is divided into five parts, excluding the introduction. A brief look at the table of contents shows the wide range of topics that he attempts to tame: polio survivors in popular music, vocal music and disability, performance as a disabled musician, deafness in popular music, and the demands of the music industry on the performer. The apparent obviousness of these topics belies the effort that it takes for McKay, or any other genre-shaping writer, to collect a disparate array of raw material and shape it into a comprehensible whole.

He includes a table of the many musicians who contracted polio in their youth and, indeed, the list is likely to surprise some readers with names as varied as Dinah Shore, Carl Perkins, Donovan and Gene Simmons…. Young and Dury were both polio survivors and the comparison of their responses and its consequent effects on their music does, in fact, make for interesting reading…. Any listener who as a casual listener, was never aware of Young’s polio but has heard ‘Helpless’ countless times as I have, is likely to be intrigued by the McKay’s reinterpretation of the song through the lens of his disability. It is one of those view shifts that lets you see a text in a whole new light.…

The lengths that [Curtis] Mayfield went through to [keep making music] … makes for one of the book’s more mesmerizing discussions, and McKay does an interesting job of juxtaposing Mayfield’s decision to that of Teddy Pendergrass who found himself at a similar crossroads.

One experience that people with visible disabilities and pop-star performers share is that they are both the objects of staring. At the beginning of his chapter on performance, McKay relates one of book’s most poignant examples of discrimination…. He cites the example of Kata Kolbert, who tried to launch her career in Britain in the 1980’s sent in demo tapes to companies who enthusiastically compared her to Kate Bush and Nico. However, when leaning that she was in a wheelchair her submission to record companies were rejected because “Her wheelchair was not sexy.”…

The final chapter covers even more territory…. McKay’s thesis is hard to dismiss.

… George McKay deserves a great deal of credit for being the first one to jump into the untested waters…. What he has done is culled the raw material, organized it in a way that provides a logical structure for making connections and thrown out some initial hypotheses for subsequent scholars to test out. In the process, he has provided a number of interesting portraits and introduced most readers to the work of musicians they did not know. This last accomplishment gives Shakin’ All Over a crossover appeal to a non-scholarly audience.… (Michael Northern, vol. 7, issue 4, December 2013)

Chronicle of Higher Education

Weekly Book List: New Scholarly books. Considers how disability is addressed in the music and performance of such artists as Johnny Rotten, Neil Young, Johnnie Ray, Ian Dury, Teddy Pendergrass, Curtis Mayfield, and Joni Mitchell. (Nina C. Ayoub, 15 November 2013)

BuzzFeed

‘Loudness is part of the pleasure, and its effects on hearing accepted, even celebrated, by fans and musicians alike’, writes British music scholar George McKay in his forthcoming book, Shakin’ All Over: Rock, Pop and Disability. He notes the perversity of a musical culture that is ‘irreversibly disabling’, with one characteristic of music-induced hearing problems being regret later in life. (‘When everyday sound becomes torture’, Joyce Cohen, March 14 2013)

Song of the Week blog: ‘#33: “Sweet Gene Vincent”, by Ian Dury’

… Here’s Professor George McKay, in a 2009 article in Popular Music called ‘Crippled with nerves’ (a Dury song title):

Ian Dury, that ‘flaw of the jungle’, produced a remarkable and sustained body of work that explored issues of disability, in both personal and social contexts, institutionalisation, and to a lesser extent the pop cultural tradition of disability. He also, with the single ‘Spasticus Autisticus’ (1981), produced one of the outstanding protest songs about the place of disabled people in what he called ‘normal land’.

The song was banned by the BBC at the time, and was forbidden from being played on TV before 6pm. The song was recently used in the opening of the London 2012 Paralympics. Dury described the song as ‘a war cry’ on Radio 4´s Desert Island Discs in 1996, a programme on which he also picked out Gene Vincent´s first single ‘Woman Love’ as one of his 8 songs (Padraig O’Connor, January 6 2013)

Cfrazerwhite, ‘Masculinity, consumption and health’

In trying to think how to develop this line of inquiry into masculinity, consumption and health I have been thinking about the role of popular music. Mention of masculinity and men’s health in the context of popular music brings to mind images of drinking and excess… For a related study – of representations of disability in popular music – see:

- George McKay, “Crippled with nerves: Popular Music and Polio”, Popular Music, 28:3 (October 2009), 341-365

- George McKay, Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability, University of Michigan Press. (28 May 2012)

The Rotarian

“There is a longstanding view about the ‘polio personality’ – a stubbornness, a bloody-mindedness, a determination to get on with life,” explains British musician and academic George McKay, author of Shakin’ All Over: Popular Music and Disability, to be published by the University of Michigan Press.

McKay, a professor of cultural studies at the University of Salford, England, has muscular dystrophy and spent time in a polio ward as a boy, before his condition was diagnosed. The “suffering, physical transformation, and isolation” that young polio victims endure can foster a sensitivity that’s vital to the work of songwriters and musicians, he says. “One can see the artistic compensation of the isolate in the music of Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and Steve Harley, all of whom have talked or sung about their childhood separation,” he says….

These musicians were among the final generation in the West to contract polio before the mass vaccinations of the mid-1950s. “They were also the generation that expressed their experiences and vulnerabilities in the new rock music,” McKay observes.

Their songs range from Young’s poetic “Helpless,” believed to describe his time as a child with polio, to Dury’s caustic “Spasticus Autisticus,” which championed people with disabilities who were coping in what he called “normal land.” Dury released the single for the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons. The BBC banned it. “Ian could exploit his disability – or people’s perception and fear of it – in manipulative and threatening ways,” McKay explains….

Doctors had recommended that [jazz saxophonist David] Sanborn play a wind instrument to help him recover from polio…. “It taught me how to adapt,” he says. “Sometimes you have to do an end run around problems. I was encouraged to play to strengthen my lungs. It did do that. But I don’t have a lot of dexterity in my left hand. I can’t raise my arm above my head. And my right leg is shorter than my left leg.

“I subconsciously adopted a certain way of playing that didn’t involve a lot of dazzling technique,” he continues. “I was always much more interested in the sound because that was where the character and personality came from. That’s your signature.”

Sanborn and other jazz musicians with disabilities face a particular challenge. “What do you do when you can’t even play an instrument ‘properly?’” McKay asks. “In jazz, a music of technique, that disqualifies you.” West Coast jazz pianist Carl Perkins, another polio survivor, became known as ‘The Crab’ because he held his left arm sideways across the keyboard. “He used his physical difference to create a musical difference.” (David Hoeskstra, ‘Polio survivors in music’, April 2012)

This book was published with the support of an Arts and Humanities Research Council research leave grant.