Community Music Now

I spent a year or so working on a proposal for a new book, co-edited with Pete Moser of More Music, about the state of play in community music today. It was to be a completely new set of essays, ideas and pieces somewhat in the form of our acclaimed 2005 collection, Community Music: A Handbook. It was to be an output of my AHRC Connected Communities Leadership Fellowship. But it never quite happened—primarily because we were negotiating with a particular leading publisher and they basically demanded guaranteed sales which we were unhappy with (I might say, speaking for myself, outraged by). And then, you know, well, books are like projects and ideas, they have a moment, a momentum, need to happen within a sort of time frame, or people move on, energy transfers. So it hasn’t happened yet. Perhaps we will revisit it.

AHRC report published: Community Music: History and Current Practice, Its Constructions of ‘Community’, Digital Turns and Future Soundings

Written by George McKay and Ben Higham (2011). [From executive summary] The UK has been a pivotal national player within the development of community music practice. In the UK community music developed broadly from the 1960s and had a significant burgeoning period in the 1980s. Community music nationally and internationally has gone on to build a set of practices, a repertoire, an infrastructure of organisations, qualifications and career paths. There are elements of cultural and debatably pedagogic innovations in community music. These have to date only partly been articulated and historicised within academic research.

Written by George McKay and Ben Higham (2011). [From executive summary] The UK has been a pivotal national player within the development of community music practice. In the UK community music developed broadly from the 1960s and had a significant burgeoning period in the 1980s. Community music nationally and internationally has gone on to build a set of practices, a repertoire, an infrastructure of organisations, qualifications and career paths. There are elements of cultural and debatably pedagogic innovations in community music. These have to date only partly been articulated and historicised within academic research.

This document brings together and reviews research under the headings of history and definitions; practice; repertoire; community; pedagogy; digital technology; health and therapy; policy and funding, and impact and evaluation. A 90-entry, 22,000 word annotated bibliography was also produced (see link below). An informed group of 15 practitioners and academics reviewed the authors’ initial findings at a knowledge exchange colloquium and advised on further investigation. Some of the gaps in research identified are: an authoritative history, an examination of repertoire, the relationship with other music (practice), the freelance practitioner career, evidence of impact and value, the potential for a pedagogy.

Annotated Bibliography of Community Music Research Review, AHRC Connected Communities Programme

This research review, consisting of a 90-entry annotated bibliography of 22,000 words, was produced as part of an AHRC Connected Communities programme project entitled Community Music, its History and Current Practice, its Constructions of ‘Community’, Digital Turns and Future Soundings.The entries range from academic monographs about alternative music education to books of music workshop exercises, government policy documents to internatinoal case studies of specific community music projects, andd more. The bibliography supports a 2,500 word report written with this same title for the AHRC.The main areas it covers include: history and definitions of community music; practice and workshop repertoire; how ‘community’ is understood; pedagogy; the impact of digital technology on creative participatory music making; health and community music therapy; cultural policy and funding; impact and evaluation. Authors: Professor George McKay, University of Salford, and Ben Higham MA FRSA, independent researcher and consultant. October 2011.

‘Community music: unorthodox music education and improvisation in Britain’ presentation at Rhythm Changes 2011 conference, Amsterdam Conservatorium

An audio recording of my presentation at the conference—on a panel looking at British jazz, along with Prof Tim Wall (talking about Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood Suite) and Prof Andrew Blake (on English jazz-rock and neglect)—was available for a time on the Rhythm Changes website, but alas no longer I fear. This came out of the AHRC project below.

An audio recording of my presentation at the conference—on a panel looking at British jazz, along with Prof Tim Wall (talking about Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood Suite) and Prof Andrew Blake (on English jazz-rock and neglect)—was available for a time on the Rhythm Changes website, but alas no longer I fear. This came out of the AHRC project below.

Community Music: History and Current Practice, its Constructions of ‘Community’, Digital Turns and Future Soundings (2011)

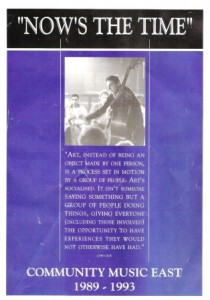

This is a project I am running with Ben Higham, founding director in 1984/5 of Community Music East (and at that time my boss). It is funded by the AHRC (£26,733), as part of the UK Research Councils’s new Connected Communities programme. Our aim is to produce a report which reviews research in the field–academic and policy–and also identifies gaps and areas for future work, which will in turn help to shape the agenda and funding priorities of Connected Communities. There are around 40 such research reviews current being written up and down the country. Ours is one of the few on community arts/media.

As part of the report-writing we are having an event for a small group of ‘critical friends’ from community music and community media at Salford University in September, at which we will present initial findings for discusion / rejection / amendment. If you are interested in being involved and you work or research in this area please do get in touch. I think we are able to pay expenses (though I better check that…).

Here is the introductory text from our proposal to the AHRC:

‘Community music for me has always been a mixture of being a social worker and a composer and finding ways of bridging that.… I passionately believe that music has the ability to make communities pull together.’ Pete Moser, Director, More Music

From the development of community music organisations in the 1980s to the more recent innovation of the Music Action Zones across the UK, from the relocation of the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra in Salford and the efforts to adopt the Venezuelan el sistema model in England (In Harmony) and Scotland (Big Noise) today, or the rise of graduate courses in Community Music at UK HEIs, we can see an enormously energetic, and perhaps surprisingly sustained, effort at community arts provision in Britain, which also has an international dimension. The aim of this review is to chart the development and current state of community music as a leading contemporary creative and pedagogic practice whose express purpose is to be situated in the community, with

reference to two other key questions.

First, in what ways has community music adapted to the introduction of new media and creative technologies? If community music was defined by its ‘congregationist imperative’ (a coming together of groups of musicians, for choir, or bandwork, and the socio-cultural implications of that version of ‘community’—which might include closeness, nostalgia, an alternative society, local identity, the therapeutic of support), how do the potentially virtual and atomising technologies of new media impact on its practice and its definitions of ‘community’?

Second, what kinds of activities and opportunities are available to, or can be discovered by, community music in the context of the Big Society? Community artists are by necessity pragmatists and hustlers, skilled at surviving at the margins, and finely attuned to the possibilities of new funding pots. Questions of voluntarism, social enterprise, the value—or lack of—placed on culture and creativity, the (new and recurrent) challenges of funding are significant.

‘Community arts and music, community media: cultural politics and policy in Britain since the 1960s’. In Kevin Howley (ed.), Understanding Community Media, (Sage, 2010), 41-52.

… To what extent is the congregationist imperative central to community media, though? By extension, are we looking at a different understanding in the context of media rather than theatre or music, of what ‘community’ means and how it is constructed? Even—does community media in some formal ways actually work against the congregationist imperative, and undermine the (potentially, whether problematically or radically) nostalgic reclamation of community which earlier or other community movements may be predicated on? Of course, media scholars have explored widely ways in which dispersed or apparently individuating media forms such as broadcasting or the internet have successfully constructed or reformatted community in their audiences—the viewing public, local radio, the chat room, or social networking, for instance. Other work has focused on communities of interest, rather than ones spatially-defined. Further, community media too can claim a similar socio-cultural tactic as community arts and festival, a certain blurring of categories, between production and consumption.  Indeed, Howley argues that this is central to community media’s political impact: ‘by collapsing the distinction between media producers and media consumers … community media provide empirical evidence that local populations do indeed exercise considerable power at precisely the lasting and organizational levels’ (2005, 3). But what I have argued here is there is an important initial distinction around the social act of congregation to be made within this specific context of community arts in relation to community media, even if it is a distinction made to be subsequently problematised. Where the production and dissemination of community arts and music is compellingly congregationist, community media and its various technologies do not rely on that same simple tactic. This matters precisely because of that same primary word, community, and what it might be claiming—that is, how the secondary word (community arts, community music, community media) changes the meaning and the experience of community….

Indeed, Howley argues that this is central to community media’s political impact: ‘by collapsing the distinction between media producers and media consumers … community media provide empirical evidence that local populations do indeed exercise considerable power at precisely the lasting and organizational levels’ (2005, 3). But what I have argued here is there is an important initial distinction around the social act of congregation to be made within this specific context of community arts in relation to community media, even if it is a distinction made to be subsequently problematised. Where the production and dissemination of community arts and music is compellingly congregationist, community media and its various technologies do not rely on that same simple tactic. This matters precisely because of that same primary word, community, and what it might be claiming—that is, how the secondary word (community arts, community music, community media) changes the meaning and the experience of community….

!['As close to a definitive book on community music as we are likely to see for some time.… [McKay’s chapter] is a short history of the movement (and an admirable introduction to its philosophy).'--Andrew Peggie, Sounding Board](http://georgemckay.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Copy-of-Communitymusic-cover-212x300.jpg) Community Music: A Handbook (co-edited with Pete Moser; Russell House, 2005)

Community Music: A Handbook (co-edited with Pete Moser; Russell House, 2005)

This is a book of ideas, a catalogue of experience, a mass of personal stories, a collection of inspiring musical exercises, and a fascinating record of community music’s roots and heritage. Community music making is exploding across Britain and this book will help you develop new insights into the practice of: running workshops making new music with people, whatever their age, culture, skill or background. Rising out of a 10 year training programme organised by More Music in Morecambe this publication has drawn on the talents of many of the key players in British community music. An essential tool for community musicians, community arts workers, music teachers, musicians from drummers to singers, workshop leaders, people involved in activities from alternative informal) education to street performance. A how-to book that should have a place on the bookcase and the music stand.

The book also contains also a series of poems by Lemn Sissay.

Includes a chapter written by me, ‘Improvisation and the development of community music in Britain; followed by, the case of More Music in Morecambe’:

The aim of this chapter is twofold. First, it traces the historical development of the idea of community music. It does this with particular emphasis on community music’s relation to aspects of the 1960s countercultural project and its legacy. This involves looking at the role of free jazz in music education, links with the burgeoning community arts movement, the radical politics and social ideas frequently claimed by those central to community music. Community music remains imbued with the spirit of improvisation, and I think it important to acknowledge the special role played by that particular music (as opposed to, say, classical music outreach teams, grassroots folk or more recent world music projects) in its development.

Second it narrates the development of the More Music in Morecambe community music project through the 1990s, its successes and (mini-)crises, its beliefs and practices. It considers the origins of MMM in some of the earlier musical/theatrical performance practice of Welfare State International, and locates MMM in the context of the rise of community music as a social-cultural phenomenon in Britain. This involves discussion of ways in which the radicalism or idealism of some of early community music has been knocked and/or maintained.

The chapter draws on and seeks to understand my experiences from the 1980s as one of the first members of Community Music East (see above), a development of the John Stevens-inspired Community Music project. I didn’t know it when I joined CME, but there was a direct link in the way it sought to work socially and musically back to the free scene of the 1960s at the Little Theatre Club in London.

One reply on “Community music”

Hi…

I have just come to the end of the HEFCE funded Lifemusic project which was part of the South East Coastal Communities Programme the aim opf which was to explore university community partnerships and knowledge exchange initiatives which supported well-being in one way or another. I have been working in the community music field for 30 years and was very pleased to get the funding which linked up with 14 other projects in community and social well-being areas. The latest volume of the International Journal of Community Music has an article about the project in it and I am just about to publish a much larger book (Lifemusic – connecting people to time) which explores my own approach to community music, well-being, musical culture etc. I am very interested in the look and sound of “Now’s the Time” especially in view of the subtitle of my book and my own conviction that we are in a critically important stage of transition, musically and culturally. Best wishes Rod