I still feel that: improvisation reaches out, breaks down barriers, challenges frontiers. Music is about liberation, jazz is about liberation, that’s the word to focus on.—Maggie Nicols, singer

My father was a semi-pro saxophonist, and I was his sometime double bassist. (That’s us playing together in the photo on the right, around 1995 or so.) Jazz has always been around our family; there’s a photo of my older sister as a girl in Glasgow in the early 1960s pretending to play my dad’s flute. When my mother was pregnant with me in 1960 she and my dad, then a budding jazzer, went to see John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie and, I think, Eric Dolphy, playing in Glasgow. Lots of people walked out of the theatre because of the unacceptable cacophony; my parents moved downstairs to the now-empty more expensive seats. The musicians saw them doing this and said, Yeah, come on. So, I was in her womb; technically that’s me at a Coltrane gig.

London Jazz Festival, 2013: McKay is a ‘leading light’ of jazz research. Nice.

Rhythm Changes fourth international conference, 2016, Jazz Utopia

A member of the organising committee for this exciting event, at Birmingham City University in the UK from 14 to 17 April 2016. Here is some information from the call for papers.

Keynote Speakers

Professor Ingrid Monson (Harvard University)

Professor Raymond MacDonald (University of Edinburgh)

We invite paper submissions for Jazz Utopia, a four-day multi-disciplinary conference that brings together leading researchers across the arts and humanities. The event will feature academic papers, panels and poster sessions alongside an exciting programme of concerts delivered in partnership with the Birmingham Conservatoire and Jazzlines.

Jazz has long been a subject for utopian longing and hopes for a better future; it has also been the focus of deeply engrained cultural fears, visions of suffering and dystopian fantasies. In its urgency and presence jazz is now here. As improvisational and transitory, jazz is nowhere. Utopia is nowhere and now here. Jazz is utopia. Or: jazz is utopian desire. Jazz Utopia seeks to critically explore how the idea of utopia has shaped, and continues to shape, debates about jazz. We welcome papers that address the conference theme from multiple perspectives, including cultural studies, musicology, cultural theory, music analysis, jazz history, media studies, and practice-based research. Within the general theme of Jazz Utopia, we have identified three sub-themes. Please clearly identify which theme you are speaking to in your proposal.

Jazz has long been a subject for utopian longing and hopes for a better future; it has also been the focus of deeply engrained cultural fears, visions of suffering and dystopian fantasies. In its urgency and presence jazz is now here. As improvisational and transitory, jazz is nowhere. Utopia is nowhere and now here. Jazz is utopia. Or: jazz is utopian desire. Jazz Utopia seeks to critically explore how the idea of utopia has shaped, and continues to shape, debates about jazz. We welcome papers that address the conference theme from multiple perspectives, including cultural studies, musicology, cultural theory, music analysis, jazz history, media studies, and practice-based research. Within the general theme of Jazz Utopia, we have identified three sub-themes. Please clearly identify which theme you are speaking to in your proposal.

- jazz identity/ies. Race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality (queering jazz, Sapphonics), disability and jazz.

- inside / outside: jazz and its others. What does jazz mean to its community of insiders and those that approach it from outside?

- heritage and archiving. The ways in which our relationship with the past enables us to imagine and construct jazz as an alternative space and practice.

Please submit proposals (including a short biography and institutional affiliation) by email in a word document attachment to: jazzutopia@bcu.ac.uk. The deadline for proposals is 1st September 2015.

Classics Revisited, Manchester University, June 2015

I’m really pleased to be part of this conference on social networks and music, which includes two sessions on what the organisers term ‘classic’ music studies. They have asked me to come and talk about Circular Breathing, which will at that time be a decade old.

Professor in Residence, EFG London Jazz Festival 2014

Professor in Residence, EFG London Jazz Festival 2014

Talking European (British) jazz: Rhythm Changes and Circular Breathing

At a Rhythm Changes project meeting at LICA, Lancaster University in March 2012. Usually project meetings are taken up with administration and bureaucracy but we determined to make some time for the discursive and interrogative during these three days. Here we are discussing the transnational and national in relation to European jazz, and I sketch the arguments I made in Circular Breathing (2005) about these questions. They revolve around three main sets of ‘outernational’ (Paul Gilroy) interactions: transatlantic exchange, British imperial / Commonwealth networks, and European gazes.

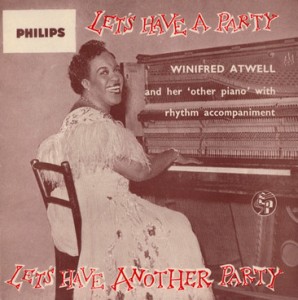

I have written a chapter for the 2014 collection Black British Jazz, edited by Jason Toynbee, Catherine Tackley and Byron Dueck. In it I revisit the musician who really intrigued and in fact charmed me from my 2005 book Circular Breathing, the lost figure of 1950s Trinidadian honky-tonk pianist Winifred Atwell.

I have written a chapter for the 2014 collection Black British Jazz, edited by Jason Toynbee, Catherine Tackley and Byron Dueck. In it I revisit the musician who really intrigued and in fact charmed me from my 2005 book Circular Breathing, the lost figure of 1950s Trinidadian honky-tonk pianist Winifred Atwell.

This piece is informed by an interview I did in 2011 with Winnie Atwell’s drummer from the 1950s hit years, Colin Bailey, available here on my website. From the chapter’s introduction:

From Tunapuna, Trinidad, Winifred Atwell (c. 1914-1983) was a classically trained ragtime and boogie-woogie style pianist who gained quite remarkable popularity in Britain, and later also Australia, in the 1950s, in live and recorded music, as well as in the developing television industry. In this chapter I outline her extraordinary international musical biography as a chart-topping pop and television star—innovative achievements for a black migrant female musician which are arguably thrown into more dramatic light by virtue of the fact that Atwell has been and remains a neglected figure in media and popular music (let alone jazz) history. I pay particular attention to her performative tactics and repertoire, developing material I introduced first in Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain (McKay 2005). But our interest in Atwell should stem not only from her position as a significant figure neglected by history, for she speaks also to definitional issues of jazz. The chapter progresses into a discussion of the extent to which Atwell is a limit case of jazz in the developing pop world of the 1950s on. Here I draw on the critical reception of Circular Breathing, the ways in which numerous reviewers responded to my inclusion of Atwell in that book, as an illustrative starting point.

Rhythm Changes: Jazz Cultures and European Identities (2010-2013)

Rhythm Changes was a 3-year research project that examined the inherited traditions and practices of European jazz cultures. The project was funded as part of the Humanities in the European Research Area’s (HERA 1) theme, ‘Cultural Dynamics: Inheritance and Identity’, a joint research programme funded  by 13 national funding agencies to ‘create collaborative, trans-national research opportunities that will derive new insights from humanities research in order to address major social, cultural, and political challenges facing Europe.’

by 13 national funding agencies to ‘create collaborative, trans-national research opportunities that will derive new insights from humanities research in order to address major social, cultural, and political challenges facing Europe.’

Led by the University of Salford, the research programme was undertaken by a team working in five European countries and drew on expertise from the Universities of Amsterdam, Birmingham City, Copenhagen, Music and Performing Arts Graz, Lancaster, and Stavanger. Research work included a number of activities such as performances, educational workshops, oral histories and interviews.

This project secured the largest grant ever at the time for a UK research project on jazz, €1m.

There is a still-active project website (click on the link above, the blue sub-heading). We met early on in various forms at Salford, Open University, Stavanger, and Amsterdam, and had later meetings in Lancaster, Copenhagen, the Institute for Jazz Research in Graz, and in London. All meetings were intellectually fulfilling,  highly productive, and great fun, but it’s fair to say that the ones where we gathered alongside or as part of a city’s jazz festival were, I think, the very best of creative and cultural endeavour. Maijazz in Stavanger 2011! I actually loved being in this project, and how (often) can you say that about an academic event? Rhythm Changes at Copenhagen Jazz Festival and at Lancaster Jazz Festival and at the EFG London Jazz Festival also—terrific.

highly productive, and great fun, but it’s fair to say that the ones where we gathered alongside or as part of a city’s jazz festival were, I think, the very best of creative and cultural endeavour. Maijazz in Stavanger 2011! I actually loved being in this project, and how (often) can you say that about an academic event? Rhythm Changes at Copenhagen Jazz Festival and at Lancaster Jazz Festival and at the EFG London Jazz Festival also—terrific.

The first of the project’s three international conferences was a fabulous event at Amsterdam Conservatory in September 2011, with great papers and panels and terrific bands on in the cool Bimhuis. Here is a video piece from canalside in Amsterdam, where I was thinking about future European jazz research.

The free improvisation movement … a lot of us have been talking about those kinds of musical innovations…. It seems to me that that’s an area that potentially, that arguably, is a new European sonicity…. Its music, its culture, its attitudinality, its educative practice–its pedagogy–its stubbornness, and definitely its radical politics. There’s one of the futures for jazz research in Europe, and we’ve got to be part of that. Free improvisation.

Our second international conference was in April 2013, at MediaCityUK, University of Salford: Rhythm Changes II: Rethinking Jazz Cultures. Information and the call for papers is here. We received around 100 proposals, which made this event, we think, proudly, the largest EVER academic jazz conference in the UK.

In September 2014 we held our third Rhythm Changes conference, back in Amsterdam. We were particularly pleased about this one as it was the first post-project event: we were be able to assess our life after funding. The theme was Jazz Beyond Borders. We hope you came and enjoyed it! If you are coming to Jazz Utopia in 2016 in Birmingham you’ll understand we have been able to ensure a future for the activity.

Sleeve note for Monk Inc CD, Propensity, 2010

Thelonious Monk’s exploration of space and silence—physically performed when he would shuffle around the piano instead of playing it—is revisited here by British band Monk Inc., with a confidently perverse twist: no piano at all. Instead there are celebrations and explorations of the Monk repertoire, standards as well as pieces from the neglected corners of his music. Rich head arrangements and sharp,

often short, solos feature throughout, on an album that, pleasingly, seems to swing less as it progresses. And it gets heavier as you listen to it too; the bass register coming to the fore on a wonderfully witty “Mysterioso”—with its tuba duet and arco solo. With this first album Monk Inc. confirm the straight-ahead pleasure and faltering strangeness that runs through the compositional Sphere of Thelonious Monk.

A two-part ABC National radio documentary, on the leading Australian music programme Into The Music, focused heavily on my research into street music and popular protest:

The intersection between protest movements and music has often occurred on the street, with musicians and music of all kinds accompanying demonstrations, marches and civil actions. Social theorist George McKay discusses how various forms of music, from trad jazz to techno, or percussion collectives to salsa, have been used as soundtracks for rebellion and radicalism.

Editorial board member. Jazz Research Journal explores a range of cultural and critical views on jazz. The journal celebrates the diversity of approaches found in jazz scholarship and provides a forum for interaction. The journal aims to represent a range of disciplinary perspectives on jazz, from musicology to film studies, sociology to cultural studies, and offers a platform for new thinking on jazz. In this respect, the editors particularly welcome articles that challenge traditional approaches to jazz and encourage writings that engage with jazz as a discursive practice.

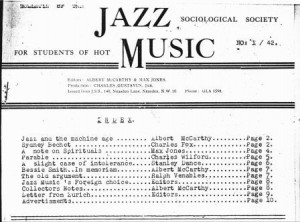

Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain (Duke University Press, 2005)

An AHRB-funded monograph (two awards). From the introduction:

This is not really (only) a book about music, about the history of the sounds of jazz in Britain, but a study of the circulation and political inscriptions in and usages of that music’s form and history. My aim is to undertake two projects, with the argument that they are related to rather than distinct from each other.

First, I want to consider African-American jazz music as an export culture, as a case study in the operation of the process or problem of ‘Americanisation’. This involves exploring questions of cultural and economic power and desire, of empires even, and the limits and problems of these. I remain surprised that jazz as a cultural form has been insufficiently considered as a prime export culture and seek to balance that. Discourses of Americanisation are always as much concerned with the import society as with the export culture itself, and I do also want to look at the effort at finding an indigenous (in this case, British) voice in an American form. Questions of imitation apply here, of course, but more importantly for the specific attitudinal culture of jazz—predicated on the authentic, the original—are questions of inauthenticity and unoriginality.

First, I want to consider African-American jazz music as an export culture, as a case study in the operation of the process or problem of ‘Americanisation’. This involves exploring questions of cultural and economic power and desire, of empires even, and the limits and problems of these. I remain surprised that jazz as a cultural form has been insufficiently considered as a prime export culture and seek to balance that. Discourses of Americanisation are always as much concerned with the import society as with the export culture itself, and I do also want to look at the effort at finding an indigenous (in this case, British) voice in an American form. Questions of imitation apply here, of course, but more importantly for the specific attitudinal culture of jazz—predicated on the authentic, the original—are questions of inauthenticity and unoriginality.

As far back as 1934, the British critic Constance Lambert recognised in his book Music Ho! one duality in jazz, that it ‘is internationally comprehensible, and yet provides a medium for national inflection’ (1934, 158). I want to explore the British experiences of jazz. Note that the focus on British should not imply a chauvinistic impulse on my part, nor is it intended to reduce the inter- or outernationalism of the music.

The book aims to be one of those awkwardly—I prefer energisingly—situated at a nodal cultural location, while acknowledging the fact that ‘different nationalist paradigms for thinking about cultural history fail when confronted by … intercultural and transnational formation[s]’ (Paul Gilroy 1993, ix). It is designed to focus the book in terms of a specific geographical and cultural cluster of dialogues, network of circulations, chart of activisms. Also, and to further problematise the US and UK chauvinistic gazes, I introduce the extraordinary global cultural mixing that has featured in British jazz practice, in part because of Britain’s own (post-)imperial connections—Caribbean, English, Australian, Indian, Scottish, South African….

!['McKay ... use[s] jazz as a way of talking about such topics as blackness, whiteness, masculinity, shifting imperial identities, and postcolonialism'. Laurie Taylor, Thinking Allowed, BBC R4](http://georgemckay.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Circular-Breathing.jpg) Second, I want to interrogate the political inscriptions or assumptions of jazz, both formally, in the notions of freedom and expression claimed for the music as an improvisatory mode, and in the particular. Here I am referring to the detailed work that follows on the cultural politics of jazz in Britain, the ways in which the cultures of jazz have been used or understood by musicians, critics, enthusiasts, as well as by its enemies, in British social and political realms. I remain surprised at the lack of attention that has been paid to the ideological development and engagement of jazz in Britain—compared with what may well be the more temporary (or temporarily innovative) subcultural practices of, say, plucking examples from my own previous writings, punk rock, festival culture, dance music in its ‘rave’ moment. Did British jazz really have no politics? Then why on earth (from circum-atlantic origins it became a global culture) choose a music forged in diaspora, struggle and celebration? And for the British left, why the attraction of particularly American—read global capitalist and military oppressor for many—music?

Second, I want to interrogate the political inscriptions or assumptions of jazz, both formally, in the notions of freedom and expression claimed for the music as an improvisatory mode, and in the particular. Here I am referring to the detailed work that follows on the cultural politics of jazz in Britain, the ways in which the cultures of jazz have been used or understood by musicians, critics, enthusiasts, as well as by its enemies, in British social and political realms. I remain surprised at the lack of attention that has been paid to the ideological development and engagement of jazz in Britain—compared with what may well be the more temporary (or temporarily innovative) subcultural practices of, say, plucking examples from my own previous writings, punk rock, festival culture, dance music in its ‘rave’ moment. Did British jazz really have no politics? Then why on earth (from circum-atlantic origins it became a global culture) choose a music forged in diaspora, struggle and celebration? And for the British left, why the attraction of particularly American—read global capitalist and military oppressor for many—music?

Also, I argue that the two projects are related: this may not always seems the case, and I would quite like the reader to be able temporarily to lose sound or sight of some of the apparently wider and more important global issues of American power, the shift of imperial authority, in the minutiae and conflicts of largely leftist and liberatory politics, campaigns, experiments, hyperbole. For micropolitics matter, are rarely as small as appearance suggests. The period of music under consideration is largely post-World War Two.

Also, I argue that the two projects are related: this may not always seems the case, and I would quite like the reader to be able temporarily to lose sound or sight of some of the apparently wider and more important global issues of American power, the shift of imperial authority, in the minutiae and conflicts of largely leftist and liberatory politics, campaigns, experiments, hyperbole. For micropolitics matter, are rarely as small as appearance suggests. The period of music under consideration is largely post-World War Two.

Contains around 40 black and white images, including photographs by the acclaimed British jazz historian and photographer Val Wilmer.

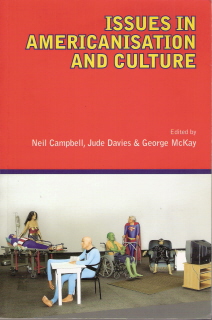

Americanisation—the cultural, political and economic influence of the USA—has played an important role in the shaping of modern Europe. This has been  the case from the 19th century, when new and old worlds were negotiating fundamental issues such as race and empire, to the 20th century, when mass media communications intensified and reconfigured the transatlantic relationship.

the case from the 19th century, when new and old worlds were negotiating fundamental issues such as race and empire, to the 20th century, when mass media communications intensified and reconfigured the transatlantic relationship.

Developments since the Cold War, including the September 11th attacks and the second Gulf War, have made this process ever more globally complex, contested and relevant. This textbook offers students an interdisciplinary and theoretically informed understanding of the cultural processes of Americanisation.

Designed with classroom use in mind, it provides a number of different routes into the debates and problems surrounding the notion of Americanisation. The editors’ introduction offers an accessible in-depth survey of the theoretical questions and is followed by two chapters which present responses to contemporary Americanisation.

Subsequent chapters are focused on specific case studies and are grouped in the following themed sections:

Histories

Histories- Cultural Geographies

- Popular Music

- Literary Narratives

- Mass Media

- Visual and Material Culture.

This collection was a key output from the HEFCE FDTL 3 project on ‘Americanisation’, for which I was the principal investigator.

2 replies on “Jazz”

Ciao Antonio, Freddie was my nephew (Zio George), and the first born of the next generation, both of McKays and Alicatas. I went to your school in Messina shortly after his death, with my sister (his mum), and was so moved by the graffiti sprayed on the walls at the entrance by his class-mates (perhaps you), in his memory, of the shock. In big blue capital letters RE DEL MARE–KING OF THE SEA. I happened to be writing Circular Breathing at the time, a very important book to me, and the dedication was my own small tribute. In fact I’d dedicated an earlier book (Glastonbury: A Very English Fair) to ‘Ran. Freddie and Emy, con amore’, and before then had written one of my early compositions to mark his birth (‘Freddie’s blues’) too.

Hi, i’m a guy from Italy. I have one question: why have you dedicated “Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain” to Federico Alicata?

Did you know Freddy? Me and Freddy were in the same class in the high scool.