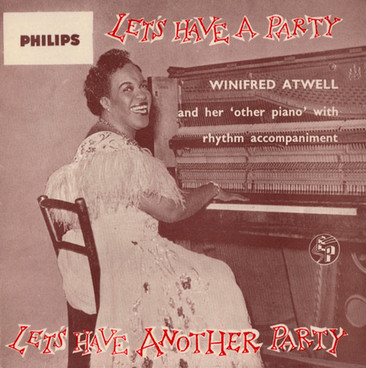

Colin Bailey was drummer with pianist Winifred Atwell in the 1950s. I interviewed him because of research I was doing on the Trinidadian honky-tonk hit parade pianist Atwell, who had 16 hit singles in the 1950s, was the first black number one artist in the British charts, and a television presenter with her eponymous show on both BBC and ITV. My key question, for Bailey as for the research, was concerned with why Atwell was still excluded from jazz histories. The chapter was published in 2014: ‘Winifred Atwell and her “other piano”: 16 hit singles in the 1950s and a “blanket of silence”?’ In Jason Toynbee et al (eds.), Black British Jazz: Routes, Ownership and Performance (Ashgate), 153-171. Click here for free open access reading of the chapter.

Bailey was born in Swindon in 1934. Now lives in California. In Australia in the early 1960s he was a member of the Australian Jazz Quartet. Became an American citizen in 1970. Playing, recording and touring nationally and internationally with Atwell in the early 1950s was a major early break in his music career. As he said to me more than once, ‘I wouldn’t be where I am if hadn’t been for Winnie’.

In his jazz, recording and performing career in the US, Bailey has worked with Frank Sinatra, Joe Pass (with whom he recorded 14 albums), Miles Davis (depping for the teenaged Tony Williams who was too young to get a club licence—‘one of the thrills of my life’), George Shearing, Benny Goodman, and many others. Also an experienced teacher, he is author of influential drum technique books, including the best-selling Bass Drum Control, has recently released the DVD Bass Drum Technique, and he is a former music lecturer at North Texas State University. His website on ‘the art of jazz drumming’ is at: http://colinbailey.com. An impressive and remarkable career for a British jazz musician!

In 1978 Bailey was flown out to Australia from the US as a special surprise guest for Atwell’s appearance on the Australian television version of This Is Your Life.

Telephone interview, May 6 2011, with corrections 13 June 2011.

____________________________________________________________________________

In July 1952 I was a young musician learning at Ivor Mairants’s Central School of Dance Music, in London. Ivor played guitar with Winnie on her recordings, and she was looking for a new drummer, so I auditioned, at his suggestion. There were two drummers, and I thought the other player was better than me, but they chose me. Later, Jan—my wife—was Winnie’s dresser, so it was a perfect arrangement, for touring and travelling. I wouldn’t have had the life, the international musical career I have had if it weren’t for Winnie.

I played on lots of the recordings, the hit singles—‘Britannia rag’ I used the sticks on the rims, I remember; I was on ‘Coronation rag’ too. When we’d recorded ‘Dixie boogie’ I do remember she complimented me on my playing. When we did recording sessions it would be Ivor on guitar, me on drums, and the best other musicians around for the rest of the rhythm section. In concert, on tour, it would be me on drums, mostly brushes. I played in the pit while she was on stage. She took me along to keep a clean time. I only ever took a snare drum with me, and would use the rest of the pit drum kit as I needed it. Actually all I ever used was a snare, a hi-hat and a cymbal, even on the recordings. There would be a bassist from the pit band or orchestra in whatever venue or city we were in—and some of them really were dreadful, because they couldn’t get the feel or the drive of her music, even though they had all the charts and could usually read well enough. So a lot of times live the bass was just a low percussive noise, an extra. Her left hand was pretty driving anyway.

On the records, no-one got a credit—only Winnie. Not even Ivor, who was a pretty well-known musician in his own right, of course.

Winnie didn’t improvise on the piano, she couldn’t improvise—she had a very good feel for boogie-woogie, and great swing, really powerful. Yes, she could swing and she had a great feel. But she couldn’t improvise and that’s why I think some people don’t want her in that list of proper jazz musicians that you’re thinking of. To that extent you can see why people say she’s not a jazzer. But we did do a lot of different material especially on those Australian tours, and some of it was from the jazz repertoire. But then again, when she did those concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London with the Philharmonic Orchestra—Grieg’s concerto—that took an awful lot of guts, and she had to practise like crazy to get up to it.

Winnie didn’t improvise on the piano, she couldn’t improvise—she had a very good feel for boogie-woogie, and great swing, really powerful. Yes, she could swing and she had a great feel. But she couldn’t improvise and that’s why I think some people don’t want her in that list of proper jazz musicians that you’re thinking of. To that extent you can see why people say she’s not a jazzer. But we did do a lot of different material especially on those Australian tours, and some of it was from the jazz repertoire. But then again, when she did those concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London with the Philharmonic Orchestra—Grieg’s concerto—that took an awful lot of guts, and she had to practise like crazy to get up to it.

She wasn’t in the jazz scene in London in any way really.

Nobody ever said anything about her being black.

The thing with Winnie was—people loved her, everybody adored her. Houses were packed and audiences really warmed to her, and she was normal, no airs and graces, even when she was top of the charts. She had such a nice personality.

In 1955 we toured Australia and New Zealand, we were away for 15 months. The houses were packed everywhere. When we came back, in February 1956, I had to make a change, a musical change—I wanted to be in a dance band, and I suppose I was finding the music I played with Winnie too restricting. The money was great, and international travel, and Winnie and Lew [Levishon, her husband, and manager] always treated me right—but I thought I needed a change. Funnily enough Jan and I were going out to Australia in 1958 just when Winnie was doing another tour there, so we ended up working all together again.

One reply on “Colin Bailey”

[…] playing jazz-derived instrumental music (solo or with a trio or quartet: piano-guitar-bass-drums). (Here you can read an interview I did with her drummer from the period, Colin Bailey.) Hers was a […]