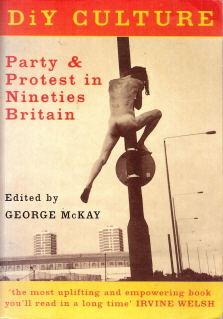

DiY Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain (ed., London: Verso, 1998)

Activist performance can be understood within a wide range of different historical frameworks. [E]xamples [that] have been particularly influential [include] … George McKay, ed. DiY Culture. Jenny Hughes and Simon Parry, Contemporary Theatre Review 25(3) (July 2015).

… George McKay’s brilliant anthology, DiY Culture: Party and Protest in Nineties’ Britain (1998), still the best single account of the new political forms of the 1990s. (Geoff Eley, ‘Politics and the city‘, H-Socialisms, June 2015)

[Writing about Benjamin Shepard’s book Play, Creativity, and Social Movements] This is the book I’d have found as a 23-year-old and flipped out to—like George McKay’s Party and Protest in 90’s Britain, discovering the MC5 or my first RTS protest. (Robby Herbst, Llano Del Rio Collective, Co-founder of Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2011)

If you were ever wondering where Reclaim the Streets came from and why the contemporary anti-capitalist movements’ actions are much more fun than their boring leftist parents, then this book will help you dance to the sounds of the new revolution. Infoshop.org reading list

For an insightful collection of reflections—historical, political and theoretical—on the milieu in which much of the more politically radical developments in UK dance culture have taken place, we refer readers to George McKay (ed.) DiY Culture (1998), a book that engages with many important issues, from Ecstasy to free parties to road protest to the legacy of anarchism. Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound (2002, p. vii)

… an excellent collection and should be read by anyone with even a passing interest in the nature of our current society, it is virtually compulsory for anyone with an interest in protest. McKay has collected accounts from nearly all of the most significant components of DiY culture, which means that there are fascinating pieces on DiY media and rave culture as well as explorations of eco-activism.… The activist engagement of the writers ensures both relevance and authority in writing. The only significant downside of this approach is that broader issues of theoretical or conceptual complexity are often left behind or are at best implied.… The accompanying introduction by McKay has, as a result, a very difficult task as it must draw out some greater complexity while also maintaining the accessibility of the chapters that are to follow. He achieves this remarkably well through an easy and accessible writing style and by avoiding purely theoretical discussions in favour of generating complexity out of the material that is to follow his introduction. McKay’s introduction is a triumph of accessible, complex scholarship. Tim Jordan, review in Time and Society vol. 10:1 (2001), 135-139

… this is the essential guide to the story so far. Phil Edwards, review in The Independent (1998)

A stellar cast of activists—including John Jordan, George Monbiot, Thomas Harding, and the editors of Aufheben—present a collection of in-depth and reflective pieces, on the contours of extra-parliamentary political protest and counter-culture. From Reclaim The Streets to video-activism, raving to tree-sitting, this is a road-map for those wanting something more than institutionalized unemployment and business as usual. AK Press (2004)

One of the few books to deal with [DiY politics] is McKay’s DiY Culture (1998), which brings together the reflections of a range of activists on the contemporary protest culture of the UK. This collection of pieces brings together a fascinating (largely biographically based) insider account of the development of this counterculture…. Like all life history material, sensitivity towards the subjectivity of the accounts is necessary. Alison Anderson, in Barbara Adam et al, eds., Environmental Risks and the Media (2000), p.98

[A] powerfully written account of the rise of direct-action politics that runs counter to the Westminster-fixated mainstream. Mark Perryman, books of the year, in New Statesman & Society (June 21 1999, p. xxviii)

George McKay’s collection is a far more accurate portrait of contemporary British protest than [the other book reviewed, Brian Macarthur’s Penguin Book of Twentieth Century Protest], in both subject matter and style. John Jordan of Reclaim the Streets, for example, offers a critique of ‘the street’ as public commons now enclosed for the private use of cars. (Peasants ancient and modern hate enclosures.) George Monbiot describes the founding of The Land Is Ours, Britain’s first land rights movement. TLIO held its first land occupation at the site near St George’s Hill in Surrey which the Diggers seized in 1649. It calls for reclamation of common-land and a right to roam. There are chapters on Squall, on the broad ambitions of Earth First! and on the ‘politics of pleasure’ – the Exodus collective, raves, warehouse parties. McKay, squatter turned academic, warns against the potential for racism in New Ageism and offers his disrespects to one of the movement’s magazines, Green Anarchist, which promotes violence. Jay Griffiths, review in London Review of Books (10 June 1999, p. 35)

… the most uplifting and empowering book you’ll read in a long time. Irvine Welsh

There are powerful voices in cultural studies who support an anti-disciplinary position and these need to be understood in relation to cultural studies’ political project against cultural elitism and towards “decanonised knowledge” as areas of experience which include activism outside the university (see McKay 1998 [DiY Culture]). Shane Blackman, ‘“Decanonised knowledge” and the radical project’, Pedagogy, Culture and Society (vol. 8:1, p. 48)

In the absence of a grand récit to inspire and guide counterculture in the nineties, its practitioners have, in typically postmodern fashion, elevated methodology to the level of substance. What emerges most clearly from this collection, beside the sense of bricolage suggested by the title, is one of interconnectedness: the underground, like the society it opposes, is – to borrow Manuel Castells’s terminology – networked. This accounts for the diversity and, often, contradictory nature of the programs marching under the DiY banner. You’ve got the neo-Luddite ‘Dongas Tribe’, who wander southern England’s green and pleasant land with horse and cart, sharing mess-fatigues with the technophiliac creators of Preston’s ART LAB, whose walls display wild assemblages of digital circuit boards and computer monitors turned into constant static. You’ve got Earth First! radicals, raging against the rape of the Mother Planet, breaking crusts with Her very rapists at benefits for out of work ex-miners. The ironies run deeper: the on-your-bike-and-do-something credo of the anti-capitalist alliance is, of course, essentially Thatcherite. ‘Ecology’, a term coined by the proto-Nazi German zoologist Ernst Haeckl in 1897, is an eminently reactionary notion (natural law and order, purity, control und so weiter) – one readily employed today, as George McKay points out in his introduction, by far right groups in the USA and Germany. Tom McCarthy, ‘The networked underground’, Mute

McKay’s collection of essays on what he calls DiY (sic) culture is broad-ranging in content, covering fanzines and video protest as well as repetitive beats and ecstasy culture. The term is defined early on as ‘a combination of inspiring action, narcissism, youthful arrogance, principle, ahistoricism, idealism, indulgence, creativity, plagiarism as well as the rejection and embracing alike of technological innovation’ (p. 2). McKay’s thoughtful introduction looks at the contradiction between some of these elements and others, such as the binary opposition between fluffy and spiky which is relatively untouched by the authors of the other books in this review. The contributors to DiY Culture are … a mixed bunch; some academic, some non-academic and some both…. [O]ne could argue that the polyvocal discourse between the covers captures perfectly the highly diversified nature of DIY culture itself. Rupa Huq, ‘Rave new world’, Entertainment and Sports Law Journal, vol. 1:3, 117-122

Only the ‘it’ in DiY is radically unclear. It certainly includes smoking ‘spliffs’, taunting the police and dancing in Trafalgar Square to ‘a type of 4/4 beat which Manchester DiY collective Network 23 dubs Enema Techno’ (‘fast, frantic electronic sequences with a boosted bass that grabs the entrails of anyone who chooses to stand in front of the speakers’). It also clearly includes animal rights and anti-road protests. But beyond that everything remains shrouded in obscurity. The few thousand participants in the DiY culture aspire to the good life. They believe that the good life is not now lived by the modern ‘consumerist’ majority. But, as the editor himself half acknowledges, DiYists could never agree on the details of what an alternative good life might look like. Accordingly, they remain silent.

The DiYists’ unattractive features are obvious. Their argumentation is shallow as well as pretentious. Their self-absorption borders on narcissism. They consistently exhibit the intolerance of which they so readily accuse others. Not least, DiYism’s irrational, even mystical strains—with their emphasis on physicality, spontaneity and the desirability of going back to the land—are all disturbingly reminiscent of early fascism. As the editor points out, the German who coined the word ‘ecology’ was himself a proto-fascist.

All the same, the DiYists do occupy a political niche in modern politics, one that would otherwise remain vacant. They express the disgust with much government policy felt by ordinary voters, even those who support mainstream political parties. More constructively, they have a capacity to focus public and media attention on issues the mainstream politicians would prefer to leave alone. In Britain, DiYists have done much to put issues of animal welfare on the political agenda and probably more than anybody else to call in question the country’s once politically impregnable road-building programme. It is, to be sure, a tyranny of the minority. But it plays a role. ‘Nettlesome but necessary’, review in The Economist (9 July 1998)

Despite the protestations of some elderly anarchists, the generation gap is as evident among anarchist propagandists as among everyone else. Emma Goldman found this when she first met the elderly Kropotkin, and found that he deprecated her emphasis on the sexual revolution. I can well believe that the people producing new anarchist journals around New York in the second world war (I am thinking of Why?, Resistance, or Politics) became aware of the generation gap when they sought collaboration from survivors from the past, whose preoccupations and priorities, and language too, were different…. Two decades later, in the 1960s, on both sides of the Atlantic, another generation of young activists discovered anarchism but usually found few in the older generation to whose language they could relate. Paul Goodman used to talk about his “crazy young allies.” And the young tended to invent a new style of anarchism of their own. This was chronicled by George McKay in his 1996 book Senseless Acts of Beauty, and, conscious a few more decades have rolled past, he now edits an updating volume about the current generation of protest in Britain. He is a Glasgow-born lecturer in the Department of Cultural Studies at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston. Simply to mention this and the background of other contributors is to draw attention to one of the gulfs between the old anarchists and the new. For the old, industrial cities call to mind the revolt of labor against capital, not new academic subjects in new flowerings of higher education. Colin Ward, Social Anarchism vol. 27 (Fall/Winter 2000)