[F]estivals, greater or lesser, each with a peculiar quality, unique and yet related to those preceding and succeeding, have built up the dance of the year.—Lawrence Whistler The English Festivals (1947)

How much longer will joss sticks rule? / They have their hair long and stringy, and wear jesus boots / Afghan coats, yeah making peace signs, maaan / Talk about Moorcock, Floyd at the Reading Festival.—Alternative TV, ‘How much longer’ (1977)

I have been interested in festivals ever since I attended my first, as a sixteen-year-old: Reading Festival in, yes, 1977. As I remember, Thin Lizzy played, and there was a moment when bassist and singer Phil Lynott, whose Fender bass had a mirrored scratchplate, was moving the bass so that his spotlight reflected off the scratchplate onto people in the crowd. And yes it did shine on me. And SAHB played, and stole the show (‘Framed’ was Alex as Jesus on the cross)—was it their last ever gig? I guess I was hooked. Other festivals followed over many years—Reading a couple of more times,  Deeply Vale and Stonehenge Free Festivals, the tail end of the East Anglian fairs, WOMAD Festivals, Outside-In Jazz Festival, Glastonbury, and many just as interesting smaller or local events. I will say that going to a new WOMAD festival, en famille, in 2008, did try my patience and enthusiasm (‘wo-MUD’), though being what I claim as first ever Professor in Residence at a pop festival, at Kendal Calling in 2011 (then the inaugural Professor in Residence at he EFG London Jazz Festival in 2014), and having a production pass at the Maijazz Festival in Stavanger as part of the Rhythm Changes project also in 2011, really revived things.

Deeply Vale and Stonehenge Free Festivals, the tail end of the East Anglian fairs, WOMAD Festivals, Outside-In Jazz Festival, Glastonbury, and many just as interesting smaller or local events. I will say that going to a new WOMAD festival, en famille, in 2008, did try my patience and enthusiasm (‘wo-MUD’), though being what I claim as first ever Professor in Residence at a pop festival, at Kendal Calling in 2011 (then the inaugural Professor in Residence at he EFG London Jazz Festival in 2014), and having a production pass at the Maijazz Festival in Stavanger as part of the Rhythm Changes project also in 2011, really revived things.

Carnivalising the Creative Economy: AHRC-funded Research on and with British Jazz Festivals

This was a small funded AHRC project of mine in early 2014, as a contribution to the AHRC Creative Economy Showcase on March 12, at King’s Place, London. We had a discussion panel of academics and festival directors, a stand at the event, with archive brochures, books, posters and leaflets, and we also made a film. Our academics were:

- Prof Martin Cloonan, Culture & Creative Arts, University of Glasgow, PI/Co-I live music and jazz festivals projects

- Prof Tony Whyton, Music, University of Salford, PI Rhythm Changes project

- Alison Eales, University of Glasgow, CDA PhD candidate.

Our festival partners:

- John Cumming, Director, London Jazz Festival

- Tony Dudley-Evans, Artistic Advisor, Cheltenham Jazz Festival

- Jill Rodger, Director, Glasgow Jazz Festival.

And our filmmaker:

We drew on five research projects across music festivals funded directly or indirectly (HERA) by AHRC, and all of which had a central collaborative impetus around knowledge exchange / co-production:

- Developing Knowledge Exchange in the Live Music Sector project (2012-13)

- AHRC Connected Communities Leadership Fellowship (2012-15)

- 25 Years of the Glasgow International Jazz Festival: Urban Regeneration, Regional Identity, and Programming Policy CDA (2011-14)

- HERA Rhythm Changes: Jazz Cultures and European Identities project (2010-13)

- The Promotion of Live Music in the UK: a Historical, Cultural and Institutional Analysis project (2008-11).

These projects represented a significant investment by AHRC in at least five current or recent jazz and related music festival-centred research projects, including one of the world’s the leading jazz festivals (according to The Guardian), London. Also included in the events was an AHRC strategic partner (Cheltenham Festivals). The festivals featured have very different organisational structures and yet each has an established track record of working with universities on KE projects. And here is our 15-minute film…

The Pop Festival: History, Music, Media, Culture (McKay, ed., 2015)

This is an international collection of essays published by Bloomsbury. (See cover above.) The book has its own pages on my website, so go here for all the information. The chapters cover festivals over the past half century or so, from UK, US, Europe and Australia, and key cultural and theoretical developments such as around theory, festival media, the digital festival, festival dress and audience performance. To my knowledge there is no key book that deals with this field, even though festivals today are a core part of the popular music and media industries—over 800 festivals each summer in Britain alone… (Though in 2011 we started to see press pieces asking if the festival bubble has burst.) From the introduction to the proposal:

‘Popular music festivals are one of the strikingly successful and enduring features of seasonal popular cultural consumption for young people and older generations of enthusiasts. In 2008 in Britain alone there were over 500 festival events, from Glastonbury Festival to local, small scale or ‘boutique’ events. The festival has cemented its place in the pop and rock, and in the seasonal cultural economy. The purpose of this book is to present the first collection of academic studies on festival culture as a whole, from its origins to a wide range of contemporary manifestations. It is an inter-disciplinary collection, drawing on Popular Music, Cultural Studies, Media Studies, Performance, Film, History, Sociology, American Studies, Psychology. The originality and timeliness of the book is severalfold:

‘Popular music festivals are one of the strikingly successful and enduring features of seasonal popular cultural consumption for young people and older generations of enthusiasts. In 2008 in Britain alone there were over 500 festival events, from Glastonbury Festival to local, small scale or ‘boutique’ events. The festival has cemented its place in the pop and rock, and in the seasonal cultural economy. The purpose of this book is to present the first collection of academic studies on festival culture as a whole, from its origins to a wide range of contemporary manifestations. It is an inter-disciplinary collection, drawing on Popular Music, Cultural Studies, Media Studies, Performance, Film, History, Sociology, American Studies, Psychology. The originality and timeliness of the book is severalfold:

- it is the first academic collection drawing from a range of disciplines to explore festival culture—a groundbreaking opportunity

- it rehistoricises the pop festival by tracing its origins to the decade of the 1950s (rather than 1960s or 1970s)

- it brings together leading scholars in the field, drawing on current funded research projects, recent doctoral scholarship of a new generation, and established academics with a track record of writing about festivals

- festival culture is booming today—students, the media, and the music industry are all interested in festivals, their history, future and how to understand them

- its international / transnational scope is evident in the case studies: USA, UK, Europe, Australia, transatlanticism, world music, the Internet

- the potential is outstanding: it is attractive to students across numerous disciplines, is international in its scope, and would likely garner media attention.’

Festival research projects

A number of recent and current national and international research projects are evidence of the surge in academic interest in festival culture. I have been involved in some capacity with each of these, as lead researcher or a research partner, invited speaker, organiser, or advisory board member.

- 2018-19 Street Music AHRC project, includes From Brass Bands to Buskers: Street Music in the UK report (open access)

- 2015-17 Cultural Heritage in Improvised Music Festivals in Europe EU-funded project

- 2015-16 The Impact of Festivals AHRC project, includes From Glyndebourne to Glastonbury: The Impact of Music Festivals in Britain report and Music From Out There, in Here: 25 Years of London Jazz Festival book (each open access)

- 2014 Curator, AHRC research talks, Cheltenham Jazz Festival

- 2014 Carnivalising the Creative Economy: AHRC-funded Research on and with British Jazz Festivals (film)

- 2013 Co-organiser, academic jazz talks, EFG London Jazz Festival

- 2012-2019 Connected Communities Leadership Fellowship (AHRC, includes research project on festival as temporary and as anti-community)

- 2010-13 ‘Rhythm Changes: (inc. jazz festivals; EU / HERA; Music/Cultural Studies)

- 2009-10 ‘Festival as a state of encounter’ (AHRC research network project; Performance Studies)

2008-10 ‘Music festivals and free parties: negotiating managed consumption: young people, branding and social identification’ (ESRC; Social Psychology)

2008-10 ‘Music festivals and free parties: negotiating managed consumption: young people, branding and social identification’ (ESRC; Social Psychology)- 2006-08 ‘Society and Lifestyles’ (inc. European pagan / folk festival event; EU FP6; Cultural Studies/Sociology).

Beaulieu Jazz Festival 1956-61

With AHRC funding I researched this festival, its origins, development, riotous moments, its mediation, and even a proto-free festival suggested by some of its more radical attendees. This work is published in chapters in Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain, and in Andy Bennett, ed., Remembering Woodstock (Ashgate, 2004). Beaulieu, in the deep green New Forest of the 1950s , was where so much of British festival culture sprang from; an extraordinary, groundbreaking event.

With AHRC funding I researched this festival, its origins, development, riotous moments, its mediation, and even a proto-free festival suggested by some of its more radical attendees. This work is published in chapters in Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain, and in Andy Bennett, ed., Remembering Woodstock (Ashgate, 2004). Beaulieu, in the deep green New Forest of the 1950s , was where so much of British festival culture sprang from; an extraordinary, groundbreaking event.

Click on the image below for some footage of a 1950s Pathé newsreel showing hip cats at Beaulieu Jazz Festival…

YOUTH HAS A FLING

A short bibliography I produced originally in 2005 for a then new website about the East Anglian Fairs of the 1970s and 1980s. Short because there is unfortunately actually little research about this important rural countercultural period (although there is now an archive to visit and study, in I think Suffolk County Council main library, Ipswich).

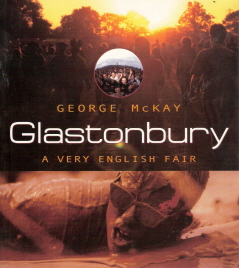

Glastonbury: A Very English Fair (Victor Gollancz, 2000)

[From the introduction] This is a book about Glastonbury, the town, its landscapes and  legends, the festivals there. It is also about festival culture more widely—the history and development of popular music festivals, the ways in which they have contributed to alternative culture, even to alternative history.

legends, the festivals there. It is also about festival culture more widely—the history and development of popular music festivals, the ways in which they have contributed to alternative culture, even to alternative history.

In spite of the weather, Britain has an extraordinary tradition of festival culture, which, as we will see, takes its inspiration from sources as diverse as Gypsy horse fairs, American rock festivals, rebirthed pagan rituals and country fairs. From trad and modern jazzers at Beaulieu in the 1950s to the New Traveller/Acid House free gathering at Castlemorton Common in 1992, festivals can be vital spaces, vital moments of cultural difference.

They live in the memories of those who were at them, as experiments in living, in utopia, sometimes gone wrong. These festivals are about idealism, being young, getting old disgracefully, trying to find other ways, getting out of it, hearing some great and some truly awful music, about anarchy and control.

They live in the memories of those who were at them, as experiments in living, in utopia, sometimes gone wrong. These festivals are about idealism, being young, getting old disgracefully, trying to find other ways, getting out of it, hearing some great and some truly awful music, about anarchy and control.

Of course, festivals can also be dull, homogenised mass events, at which crowds worship bad music played too loud in unconscious echo of sub-fascist ritual—but mostly those are the heavy metal ones. (Joke!) Key features of festival culture in Britain include a young or youthful audience, open air performance, popular music, the development of a lifestyle, camping, local opposition, police distrust, and even the odd rural riot.

To both chart and to celebrate the counterculture’s tribal gatherings, I look in detail at Glastonbury Festival, which has been at the centre of the movement for thirty years, on and off, and which reflects the changes in music and style, in political campaigning, in policing and festival legislation over all that time. Its audiences include old and young hippies, punks, folk fans, ravers, neo-pagans, and generations of activists, dreamers, fun-seekers, musicians, pilgrims, as well as the many city-dwellers who come down on Glastonbury for that annual hit of green freedom (within the fences, anyway).

The book moves between the micro-perspective of what Somerset dairy farmer and Glastonbury Festival organiser Michael Eavis calls his ‘regular midsummer festival of joy and celebration of life’, and the macro-perspective of what sociologist Tim Jordan has identified as ‘the importance of post-1960s festivals to ongoing radical protest’. I make no apologies for positioning my version of festival culture within a political praxis and discourse, however problematic. It is though a politics which admits pleasure, whether of pop and rock music, of temporary (tented) community, of landscape and nature under open skies, of promiscuity, of narcotic. The version of festival culture I offer here contains all these features. Sometimes. In varying degrees.

The book moves between the micro-perspective of what Somerset dairy farmer and Glastonbury Festival organiser Michael Eavis calls his ‘regular midsummer festival of joy and celebration of life’, and the macro-perspective of what sociologist Tim Jordan has identified as ‘the importance of post-1960s festivals to ongoing radical protest’. I make no apologies for positioning my version of festival culture within a political praxis and discourse, however problematic. It is though a politics which admits pleasure, whether of pop and rock music, of temporary (tented) community, of landscape and nature under open skies, of promiscuity, of narcotic. The version of festival culture I offer here contains all these features. Sometimes. In varying degrees.

The vibrant adventure that is the social phenomenon of festival culture that has developed since the 1950s in Britain  has touched several generations now. I hope you recognise your festival here; it has indeed ‘built up the dance of the year’. Be generous and optimistic: remember the good parts, for memory can change the world. (A bit. Sort of.) I hope you recognise your Glastonbury here. Even if you don’t remember it.

has touched several generations now. I hope you recognise your festival here; it has indeed ‘built up the dance of the year’. Be generous and optimistic: remember the good parts, for memory can change the world. (A bit. Sort of.) I hope you recognise your Glastonbury here. Even if you don’t remember it.

Glastonbury contains many black and white and colour images, and a Time-line of Festival Culture 1951-1999. Many of the photographs are by Alan ‘Tash’ Lodge.

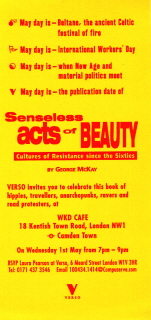

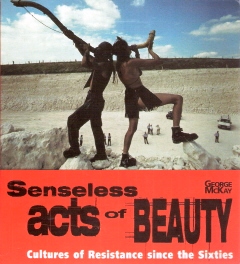

Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties (1996)

Atti Insensati di Bellezza: Le Culture di Resistenza Hippy, Punk, Rave, Ecoazione, Diretta e Altri TAZ (Italian translation, two editions, 2000)

Atti Insensati di Bellezza: Le Culture di Resistenza Hippy, Punk, Rave, Ecoazione, Diretta e Altri TAZ (Italian translation, two editions, 2000)

This was my first book. With hindsight, it was one of those timely books,caught the moment, made a bit of a splash. It draws on some of my own experience, and on old diaries too, where they were any good. It covers 30 years of countercultural activity, after the 1960s long decade. Three chapters in particular have a British festival focus, looking at

- the free festivals and fairs of Albion of the 1970s/80s,

- the ‘New Age Traveller’ movement of the 1980s,

- and the rave/free party movement of the 1990s.

Extract from Chapter 1: The Free Festivals and Fairs of Albion… Free festivals are most notoriously framed in America in 1969 by the utopia of Woodstock and—a mere four months later—the dystopia of Altamont, Hell’s Angels murdering while the Rolling Stones play ‘Sympathy for the Devil’. One writer in the underground International Times viewed things in this way: ‘Woodstock is the potential but Altamont is the reality’. According to Elizabeth Nelson, ‘[a]lthough  Altamont hardly stemmed the flow of free festivals in Britain, it almost certainly affected the attitude of the British counterculture to what might be termed the festival idea’. I’m not sure about this: Woodstock and Altamont are so early in the timetable of British free festivals, they’ve almost been and gone before the British scene is in any way established. (It may be that the influence of Woodstock is felt later, when the movie is released and distributed in Britain. Nigel Fountain similarly suggests that the film of the 1967 Monterey festival exported the romance, the desire of such events to Britain.) In 1969 the British scene is utterly embryonic; in fact, free festivals in Britain are one activity that can clearly be said to have outlived the hippy counterculture from which they sprang.

Altamont hardly stemmed the flow of free festivals in Britain, it almost certainly affected the attitude of the British counterculture to what might be termed the festival idea’. I’m not sure about this: Woodstock and Altamont are so early in the timetable of British free festivals, they’ve almost been and gone before the British scene is in any way established. (It may be that the influence of Woodstock is felt later, when the movie is released and distributed in Britain. Nigel Fountain similarly suggests that the film of the 1967 Monterey festival exported the romance, the desire of such events to Britain.) In 1969 the British scene is utterly embryonic; in fact, free festivals in Britain are one activity that can clearly be said to have outlived the hippy counterculture from which they sprang.

There is an earlier American film influence on the development of British music festivals, namely the films of Newport and other jazz festivals. In spite of the vagaries of climate, Britons too wanted to experience Jazz On A Summer’s Day. ‘[S]ince the early 1960s the British had gathered in wet fields to hear jazz, [and] 1968 had seen an outbreak of small festivals, with even a fair-sized event (12,000) on the Isle of Wight, . . . [but] 1969 was the year that rock festivals took off in Britain’. Blind Faith at Hyde Park in June, the Rolling Stones there in July, Bob Dylan on the Isle of Wight in August. It’s ironic and apt that the free festival movement in Britain rather stumbled into existence–the White Panthers helping the fences come down at the final Isle of Wight in 1970.

Another event which quickly turned into a kind of free festival, what may have been Britain’s first consciously organized along non profit-making lines, was ‘Phun City’. This event was organized by then underground writer Mick Farren, inspired by what he saw–following Woodstock in August 1969–as the utopian possibility of connecting counterculture with rock music.The event was publicized through the underground press, including one of the most widely circulating hippy-politico magazines, International Times. July 1970 was the date, described retrospectively by Nigel Fountain as the underground’s ‘Indian summer’. Shambolic organization and finances, court injunctions and the local Drugs Squad, led what was originally planned as a profit-free enterprise to end up effectively as a free festival, with between–depending on who you read–three and ten thousand people camped in the woods by Worthing, Sussex. Free music, free food, even free drugs, as at least one dealer ‘sold dope until he had covered his costs. Then he gave it away’.

Actually, the early free festivals–as opposed to simply one-off free concerts–were commercial events which either went wrong, or were challenged or overwhelmed by their audiences: a month after Phun City the final Isle of Wight festival attracted upwards of a quarter of a million people, many of whom were unhappy about the rip-off prices of admission, food and general musical organization. Within a couple of days the fences were torn down and a free festival declared, just like Woodstock, complete with food shortages outside the now physically-guarded VIP enclosure. The following summer, underground rockers the Edgar Broughton Band planned to take the idea of festival on the road. A free tour of British seaside towns was organized. The resort of Blackpool, a self-proclaimed centre of pleasure and indulgence, reacted strongly to the possibility of such subversives coming, and ‘slapped a ban on all such free shows for the next 25 years’.

Free festivals are practical demonstrations of what society could be like all the time: miniature utopias of joy and communal awareness rising for a few days from grey mundane of inhibited, paranoid and repressive everyday existence. . . . The most lively [young people] escape geographically and physically to the ‘Never Never Land’ of a free festival where they become citizens, indeed rulers, in a new reality.

Senseless Acts of Beauty contains numerous black and white images—photographs, radical ephemera, record covers, posters and flyers. [In fact, including such visual materials as an alternate strand of historical example—with scopophilic intent—has become one of the frequently-employed textual strategies of my books, both academic and general, ever since this first one.]

One reply on “Festivals”

I visited your website after reviewing your annotated bibliography on the impact of events.

I am taking another perspective on events and festivals, examining the planning for and regulation of temporary land uses for the purposes of events from a land-use management lens. I have attached a paper that summarises the research.

I would be interested in your knowledge about the use of policies and rules to control the location and timing of festivals in the UK.