DIY = Do It Yourself

I am pleased to note that this website, georgemckay.org, is a recommended resource in Ruth Kinna, ed. The Bloomsbury Companion to Anarchism (2012), where it is described as containing ‘commentary on cultural studies, music, disability, do-it-yourself (DiY) information about current academic work and festival reports’.

Radical Gardening: Politics, Idealism & Rebellion in the Garden (2011)

At one of the radical bookshop talks I gave around the UK in 2011-12 with this book someone questioned the word ‘idealism’ in the subtitle and suggested it should be ‘ideology’. It is indeed the latest of my books of cultural protest, of the (are you ready) horticounterculture.

_________________________________________________________________________________

‘”A soundtrack to the insurrection”: street music, marching bands and popular protest’ (2007)

I know that it’s spring and dark winter is past when I hear the sound of the Protestant marching bands. It warms my heart to hear Protestant feet marching once again. For it is the marching bands that are keeping open roads for Protestants to walk upon.–Unionist politician Ian Paisley, at a unionist parade in Northern Ireland, 1986

Hey, normal life ends here folks, there is a marching band in your Starbucks, you’re not going to work today!—Infernal Noise Brigade at Seattle anti-capitalist actions, 1999

I was invited to write a piece for a 2007 special issue of the cultural studies journal Parallax, on the theme of ‘Inchoate cartographies’. I wrote about the development of marching bands on political demon strations and parades. (As usual on this site, click on the title link above to go to an open access online version of some or all of the text.) From the article’s introduction:

What happens in social movements when people actually move, how does the mobile moment of activism contribute to mobilisation? Are they marching or dancing? How is the space of action, the street itself, altered, re-sounded?

The employment of street music in the very specific context of political protest remains a curiously under-researched aspect of cultural politics in social movements. Many campaigns are still reliant on a public display, a demonstration of dissent, which takes place on the fetishised space of the street. Such demonstrations claim (some activists say reclaim, suggesting a Golden Age of utopian past rather than future) the transient space of the street, occupy it in short-lived transformative experiments (the day of the march), and do so with sets of structures including what John Connell and Chris Gibson call ‘aural architecture’ (the live performance of marching music).

What interests me here are the extraordinary sounds of this street music, which is not an everyday practice, but a music of special occasion. By looking at the marching bands of different socio-political and cultural contexts, primarily British, I aim to further current understanding of the idea and history of street music itself, as well as explore questions of the construction or repositioning of urban space via music—‘how the sound of music can alter spaces’; participation, pleasure and the political body; subculture and identity.

These marching bands are resounding in their similarities—choreography, the rhythm of drumming, uniforms, the contradictory gamut of military and pseudo-military practice—and also so very different from one another—contextually, of course, but in terms of ideology, the politics of repertoire, gender, cultural tradition and innovation, too. For, while indeed social ‘[m]ovements are seen to be the breeding ground for new kinds of ritualised behaviour’, as Ron Eyerman and Andrew Jamison have argued in Music and Social Movements, some common cultural practices can cut across campaigns in the mobilisation of tradition….

__________________________________________________________________________

Society and Lifestyles EU Framework Programme 6 research project (2006-2008)

An EU FP6 collaboration between 15 European universities. According to the project director, Prof Egidija Ramanauskiate of Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania,

A unique feature of the project was the establishment of an experimental environment for communication among the groups, the researchers and the members of the society-at-large. Two academic cultural forums (that is, laboratories for communication between academics, subcultural and new

religious movement group members and the wider public) were organized in Lithuania both at VMU and in a series of tents at the Black Horned Moon festival on the island of Lake Zaraso. At these sites, subcultural as well as religious communities (goths, hippies, heavy metal enthusiasts, bikers, punks, devotees of Hare Krishna, neo-pagans, members of the Anastasija movement and others) shared their values, subcultural practices and religious beliefs with each other. Also in these experimental public/academic/practitioner spaces, project researchers from different countries delivered academic

readings on the findings from their fieldwork.

The summative conference at the University of Salford in 2008 included a performance by veteran UK anarchist, Penny Rimbaud of Crass.

A key academic output for the project was the international collection of essays, Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe (McKay et al eds., Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009. Cultural Identity Studies vol. 15). From McKay and Michael Goddard’s introduction to part one, on (post)subculture:

This section of the book contains essays which explore recent and current subcultural and related practices and formations in a geographical spread across Eastern Europe, the Baltic states and Russia. We are concerned with presenting material that forms new studies in empirical case form as well as that which considers contemporary theorizations, across areas of style (fashion), popular music and post-socialist lifestyle. Our aims are that these essays contribute to the further understanding of a continued fascination on the part of some young and some not-so-young people with aspects of subcultural identity, that the case studies themselves help to inform current debates on the scholarship of post-subcultures in a post-socialist context and that the outstanding dynamic between national identity and transnational cultural exchange in a global context is further explored. In this brief introduction we also want to outline theoretical and contextual questions that underpin much of the material that follows.

__________________________________________________________________________

‘Subcultural innovations in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’ (2004)

While we rebel with marches and music and words they’ll fight us back through the propaganda of ‘popular’ media. Crass, ‘Nagasaki nightmare’ sleeve notes

This article was commissioned for and published in a special issue of the journal Peace Review (vol. 16:4, Dec. 2004, pp. 429-438) on, I think, youth and (sub)culture. A PDF of the article is accessible by clicking on the title, above. From the introduction:

In times of war and rumours of peace, when ‘terrorism’ and ‘torture’ are being revisited and redefined, one of the things some of us should be doing is talking and writing about cultures of peace. In what follows, I ask questions about the place of culture in protest by considering the cluster of issues around the Campaign for Nuclear Disannament (CND) from its founding in London in 1958. I look at instances of (sub)cultural innovation within the social and political spaces CND helped make available during its two high periods of activity and membership: the 1950s (campaigning against the hydrogen bomb) and the 1980s (campaigning against U.S.-controlIed cruise missiles). What particularly interests me here is tracing the reticence and tensions within CND to the (sub)cultural practices with which it had varying degrees of involvement or complicity. Il is not my wish to argue in any way that there was a kind of dead hand of CND stifling cultural innovation from within; rather I want to tease out ambivalences in some of its responses to the intriguing and energetic cultural practices it helped birth. The CND was founded at a significant moment for emerging political cultures. Its energies and strategies contributed to the rise of the New Left, to new postcolonial identities and negotiations in Britain, and to the Anti-Apartheid Movement. In what ways did it attempt to police the ‘outlaw emotions’ it helped to release?… There are four primary cultural/social innovations linked to CND that interest me: the Aldermaston march (1958 to mid 1960s); the rise of Crass and anarchopunk (1979-1984); the Glastonbury CND Festival (1981-1990); and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp (1980s).

____________________________________________________________________________

Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural & Political Protest (Routledge, 2002-2010)

I was founding co-editor of this academic journal for its first seven or eight years, during which it expanded from two to four issues per year; I was responsible for cultural and media studies submissions.

Social Movement Studies is an international and inter-disciplinary journal providing a forum for academic debate and analysis of extra-parliamentary political, cultural and social movements throughout the world. Social Movement Studies has a broad, inter-disciplinary approach designed to accommodate papers engaging with any theoretical school and which study the origins, development, organisation, values, context and impact of historical and contemporary movements active in all parts of the world. We understand our inter-disciplinary approach to include both contributions that engage with particular schools of thought relevant to social movements and popular protest and contributions that extend across disciplinary boundaries. Social Movement Studies aims to publish soundly researched analyses and to re-establish writing as intervention. From this broad and inclusive perspective we are interested in contributions dealing with social movements, popular protests and networks that support protest. This includes contributions dealing with but not restricted to:

Social Movement Studies is an international and inter-disciplinary journal providing a forum for academic debate and analysis of extra-parliamentary political, cultural and social movements throughout the world. Social Movement Studies has a broad, inter-disciplinary approach designed to accommodate papers engaging with any theoretical school and which study the origins, development, organisation, values, context and impact of historical and contemporary movements active in all parts of the world. We understand our inter-disciplinary approach to include both contributions that engage with particular schools of thought relevant to social movements and popular protest and contributions that extend across disciplinary boundaries. Social Movement Studies aims to publish soundly researched analyses and to re-establish writing as intervention. From this broad and inclusive perspective we are interested in contributions dealing with social movements, popular protests and networks that support protest. This includes contributions dealing with but not restricted to:

- movements of all types including gender, race, sexuality, indigenous people’s rights,

- disability, ecology, peace, youth, age, religion, animal rights and others,

- forms of communication, media and representation engaged with social change, including the Internet and cybercultures,

- networks of support and broad ‘ways of life’ engaged with alternative social systems,

- appraisals of popular reactionary movements or populist movements of the ‘right’,

- subcultures and countercultures, including such things as the place of dance, pleasure or music in resistance,

- identities and the construction of collective identities

- relations between protests and social structures, including situating movements in local, regional, national, international and global socio-economic and cultural contexts

- theoretical reflections on the significance of social movements and protest.

____________________________________________________________________________

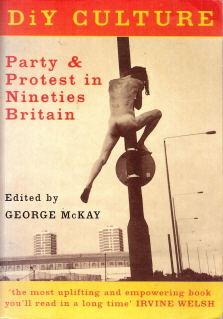

DiY Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain (McKay ed., Verso, 1998)

DiY Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain (McKay ed., Verso, 1998)

One of my more influential books! From the ‘Notes towards an intro’:

In the mid-Fifties the jazz revival had produced an offshoot, a musical phenomenon which became much bigger than itself, the skiffle craze. Skiffle was do-it-yourself music, primitive jazz played on home-made or improvised rhythm instruments as an accompaniment to the singing of folk-blues and jazz songs of the simpler and more repetitive sort.… It is significant that 1958, the year that saw the climactic boom in jazz popularity, also produced the first Aldermaston march. The jazz revival and the rise of CND were more than coincidental; they were almost two sides of the same coin. —Ian Campbell, ‘Music against the bomb’

The venue was the Roundhouse.… The posters went up, in a scattered fashion, around the autumnal city. ‘All Night Rave’ they proclaimed.… That Saturday, 15 October, the ravers had come home to roost, this time accompanied by Strip Trip, Soft Machine, a steel band, and Pink Floyd.… It didn’t even start until 11 p.m. How the ravers were to find their way out of Chalk Farm and into their bedsits would also be a challenge worthy of the do-it-yourself times into which the metropolitans were moving.—Nigel Fountain, Underground

In the first week of October, both Melody Maker and Sounds ran extensive features on the festival which propagandized the new generation. Caroline Coon uttered for the first time the incantation: ‘Do It Yourself’.… Mark P. had been one of the first people fully to articulate the ‘Do it yourself’ ethic and in Sniffin’ Glue 5 he had lain down the gauntlet: ‘All you kids out there who read “SG” don’t be satisfied with what we write. Go out and start your own fanzines’.—Jon Savage, England’s Dreaming

In the eighties, a lot of people who were hacked off with the way we were living, or were just plain bored, got off their arses and did something about it.… DiY culture was born when people got together and realized that the only way forward was to do things for themselves.… Ingenuity and imagination are the key ingredients.… Free parties, squat culture, the traveller movement and later Acid House parties pay testament to the energy and vision of people who decided it was now time to take their destinies into their own hands.—Cosmo, DiY activist

that’s the real strength of Newbury and all the 90s counterculture protests: we’re not fighting one thing we don’t like; we have a whole vision of how good life could and should be, and we’re fighting anything that blocks it. This is not just a campaign, or even a movement; it’s a whole culture.—Merrick, Battle for the Trees

These five epigraphs offer a pretty neat (too neat) and corresponding cartography of DiY Culture in Britain since the Second World War. DiY Culture, a youth-centred and -directed cluster of interests and practices around green radicalism, direct action politics, new musical sounds and experiences, is a kind of 1990s counterculture. DiY Culture likes to think that this is the case and says so often enough. The purpose of this book is to open up some space for a number of key figures and other happeners in it to tell their stories, their histories, their actions and ideas. Like the 1960s version we tend to associate the word ‘counterculture’ with, DiY Culture’s a combination of inspiring action, narcissism, youthful arrogance, principle, ahistoricism, idealism, indulgence, creativity, plagiarism, as well as the rejection and embracing alike of technological innovation. There is now quite a lot of writing about it that says ‘We are new, we are different, we are great, cheeky, active’; there’s surprisingly little writing, especially from within, that starts ‘Are we? Is this new?’

These five epigraphs offer a pretty neat (too neat) and corresponding cartography of DiY Culture in Britain since the Second World War. DiY Culture, a youth-centred and -directed cluster of interests and practices around green radicalism, direct action politics, new musical sounds and experiences, is a kind of 1990s counterculture. DiY Culture likes to think that this is the case and says so often enough. The purpose of this book is to open up some space for a number of key figures and other happeners in it to tell their stories, their histories, their actions and ideas. Like the 1960s version we tend to associate the word ‘counterculture’ with, DiY Culture’s a combination of inspiring action, narcissism, youthful arrogance, principle, ahistoricism, idealism, indulgence, creativity, plagiarism, as well as the rejection and embracing alike of technological innovation. There is now quite a lot of writing about it that says ‘We are new, we are different, we are great, cheeky, active’; there’s surprisingly little writing, especially from within, that starts ‘Are we? Is this new?’

For this book I wanted in-depth pieces of writing by people involved in DiY Culture. For someone like me—a mid- (okay, late-)thirties academic, with two kids, urban-born and country-raised,  with a past in punk, anarchism, experimental music—the explosion of positive energy around what I found out was being called DiY was a keen rejoinder to the cynical narratives maybe activists of my generation had offered about the depoliticized nature of Thatcher’s Children.

with a past in punk, anarchism, experimental music—the explosion of positive energy around what I found out was being called DiY was a keen rejoinder to the cynical narratives maybe activists of my generation had offered about the depoliticized nature of Thatcher’s Children.

Green Anarchist writer Stephen Booth has observed with some accuracy that, in the Britain of the 1990s, ‘the main area of political dissent and resistance to the status quo has not been the struggle in the workplace–indeed there has been virtually no struggle there at all beyond tokenistic one day stoppages, and many people do not even have a workplace. The main area of dissent has been in the anti-roads movement and in animal rights’. This local view of the situation is widened out by the internationalist perspective offered by Guardian writer John Vidal:

there is increasing evidence that globalism and localism … may be intimately linked, opposite sides of the same coin. The more that corporations globalize and lose touch with the concerns of ordinary people, the more that the seeds of grass-roots revolt are sown; equally, the more that governments hand responsibility to remote supranational powers the more they lose their democratic legitimacy and alienate people.

In the space between such local and global readings as Green Anarchist‘s and the Guardian‘s are located these ‘notes towards an intro’. My aim in writing them has been not to offer an authoritative view of 1990s protest and radical culture, but to outline some historical strands, explain some social context, raise what I think are some significant problems.

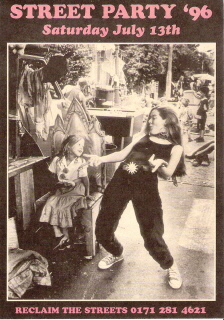

The chapters following these ‘notes’ deal with the often overlapping achievements of DiY Culture, in the particular areas of direct action campaigning (Earth First!, road protests, Reclaim The Streets), the development of its own media (SchNEWS, SQUALL, Aufheben, Undercurrents, Do or Die), and its own spaces of protest, pleasure and living (the Exodus Collective, The Land Is Ours, warehouse and free parties, the E generation). These chapters have their own authority, are written by DiY Activists and cultural workers.

DiY Culture includes black and white images, and cartoons by Kate Evans.

____________________________________________________________________________

‘Really revolting party outfits’ Times Higher Education article about protest and new book, DiY Culture (13 March, 1998)

The snot-green contumacy of punk blew me away in 1977. As a 16-year-old growing up in Norwich I really believed in punk’s liberatory possibilities,and the anarcho-punk scene of the early 1980s helped frame my politics further. By 1981 I was a student at Hull College of Higher Education, reading English, involved in the anarchist movement and taking part in those ritual early 1980s marches. I marched against racism, the bomb, unemployment and the Falklands war; I marched for Troops Out of Ireland and, later, the miners. These were the punctuating moments in what, with hindsight, was a maelstrom of traditional activism that revolved around weekly group meetings and the Roneo duplicator.

At the time I wondered whether we were the last in that lineage of student activists whose touchstone was May 1968 (though I was just seven in that rebellious year). Everyone in our world was some sort of socialist,all the way from the broad left to the anarchist, so you were never short of the opportunity for a good argument.

Through the 1980s I began to shift away from organised political activism and started to embrace what would later become called lifestyle politics (“the replacement of engagement by narcissism”, as one ex-friend put it to me contemptuously). Lifestyle politics is the concentration of political activity on issues of personal identity, whatever matters to you—whether it be living in a squat, organising underground events, or being at a protest camp.

A turning point for me was 1984. In that year I saw punks and hippies merge in a vibrant, neo-tribal celebration of the summer solstice at the last Stonehenge Free Festival, (the last because in 1985 the police stopped would-be revellers on the road and trashed their convoys in the “Battle of the Beanfield”). Following a long hitch-hike from the North, passing endless convoys of police vehicles looking for miners and flying pickets to sweep up, I first glimpsed the stones, dwarfed by a shimmering megalopolis of marquees, trucks, tepees and columns of wood smoke. The scale of the event shocked me.

In some ways, people of my generation passionately wanted to believe in the myth that our successors, those children who had known no government other than Thatcher’s, were children without politics, the “me” generation. It was a mythology that made our own political activism more important, it made us seem so heroically terminal. And yet, party and protest, the combination of lifestyle and resistance politics, if you like, seems stronger now than ever. Moving in 1992 to a job as lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston, I realised that there it was, down the road from me, that in fact it had been there all along.

In East Lancashire in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a new kind of underground culture was springing up, one located in those ubiquitous northern icons of redundancy, disused factories, but with its links to the older protest movements of the 1960s. Weekly a small group would break into one of Blackburn’s disused factories, set up their equipment, pass the word round and prepare to rave the weekend away. Here, just as in the hippy movement of the 1960s, was a subculture around a politics of pleasure. And as if to prove that connection of subculture with protest the biggest campaign against road-building to date took place in East Lancashire in 1994-95. Aimed at halting the building of a link road between Blackburn and Preston off the M65, protesters built villages in trees with precarious aerial walkways and in countless other ways sought to save the lovely Lancashire countryside.

It did not work—I drove past the link road the other day—but it serves as an illustration of the different kind of politics of today’s youngsters. While we were great at sitting around talking problems through,today’s activists altogether prefer doing things. In fact, few talk of “demonstrations” any more, but of “actions” and “blockades”. These are the “green children of Thatcher”, as some have knowingly called themselves, and their activism has a new name—DiY culture. As one activist explains, “ingenuity and imagination are the key ingredients”. Free parties, squat culture, the traveller movement—all are evidence of groups of disenfranchised people doing things for themselves. As Merrick puts it, in his book about the Newbury bypass protest, Battle for the Trees, “we’re not fighting one thing we don’t like; we have a whole vision of how good life could and should be, and we’re fighting anything that blocks it. This is not a campaign, or even a movement, it’s a whole culture.”

Coming from an older generation and, worse, being seen as an ex-activist, I could only do wrong as I embarked on academic research into DiY culture. In DiY publications like Green Anarchist and Earth First!’s Do or Die, my book about post-1960s counterculture, the first really to deal with road protest, received only bad reviews. The accusations were that I was packaging rebellion as a glossy product, or that I was misrepresenting it. One review first accused me of not checking my facts and then criticised me for not including everything said to me by a group of activists I had phoned to check some facts.

The unarticulated accusation in these reviews was that I was somehow stealing their story, and even history. The former I could understand: after all, DiY culture is premised on the ownership of its actions and spaces by the people involved in it. The latter I resented: there was no recognition that, actually, maybe people like me were their history. My own research continues to uncover historical correspondences only ten or 20 years apart. The Squatters’ Estate Agency set up in 1996 by those tireless DiY-ers at Justice?, an organisation set up to contest Michael Howard’s 1994 Criminal Justice Act which outlawed so many DiY pastimes, captured the media’s imagination with its subversive cheek. The idea was that you could collect details of “desirable residences” to squat in your area, including number of bedrooms, size of garden, and so on. No one, though, seemed to remember the remarkably similar Ruff Tuff Cream Puff Squatters’ Estate Agency which, yes, had captured the media’s attention with its subversive cheek – in London in 1974.

Of course there are difficulties writing about a subject both so contemporary and so dispersed. My research strategies are those of the journalist: phone, fax, email. (Unlike many of their technophobic 1960s counterparts, 1990s activists are surprisingly online.) To contact those activists who live in the deep countryside, a more sedate chain of communication opens up: a letter c/o address, to be picked up whenever… by someone passing through. On more than one occasion this has meant wandering the countryside looking for the tell-tale plumes of smoke from wooded glades to find a particular group of “organic nomads”.

But despite these difficulties more and more academics are turning to this new subject of study. There is now an annual conference on Alternative Futures and Popular Protest at Manchester Metropolitan University, a new MA in politics of change at the University of East London, as well as frequent conferences on green issues and on dance culture.

Last year, incredibly, much of the talk was that DiY politics would fade with the election of new Labour. Ironically, what we have seen instead is the continuing rise of extra-parliamentary activity, if in unforeseen forms. These range from the recent multi-issue Countryside March in London to the more bizarre: landowners rather than land rights activists, hunters rather than hunt saboteurs, threatening the kinds of direct action they have previously witnessed being so effectively used against themselves. It remains to be seen how DiY culture will respond to the appropriation of its favoured tactics. But this development is further evidence of what I have always thought: that political culture outside Parliament is so much more interesting.

____________________________________________________________________________

I wasn’t quite sure where I should put this on the website. It’s one of a series of articles I wrote in my early postdoctoral days, or in one case while I was still a research student, that explored work related to the PhD. These were accepted for journals like Critical Quarterly, Foundation, and in this instance Science-Fiction Studies. They dealt with politics and theory, utopia and dystopia, radical culture—not so very different from what I went on to do in lots of ways, except that these articles had a literary focus. Abstract (sounds a bit tortuous, but hey I was still working my way through theory. Gets better, honest):

This article engages with recent theoretical work which has developed the notion of texts offering models of reading for their readers. More specifically, it looks at ways in which science-fiction texts position readers, and at the ways in which political texts comment on their own reading processes and propagandizing strategies. A comparative analysis of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Katharine Burdekin’s neglected feminist dystopia Swastika Night (1937) focuses on a textual device common to both. The reading process of subjects in dystopia is explored: both Winston Smith and Burdekin’s Alfred are presented reading political texts, secret books. Swastika Night and Nineteen Eighty-Four are political texts intended to influence readers, embedded in which are scenes where political texts influence readers. The article discusses the significance of these scenes, which are both self-referential and extra-textual. It identifies and explores some of the problems of the parallel activities of the reader in the text and that outside the text—you, me. It concludes by arguing for an auto-critical impulse in dystopia, which is also a source of narrative—even propagandizing—energy.

2 replies on “DIY, protest”

[…] décadas depois, o movimento punk foi beber na cultura DIY, de onde já havia saído o skiffle craze, tipo de jazz no qual os […]

[…] décadas depois, o movimento punk foi beber na cultura DIY, de onde já havia saído o skiffle craze, tipo de jazz no qual os […]