Addressing the Gardeners’ Benevolent Institution in 1852, Charles Dickens commented that ‘even the prisoner is found gardening in his lonely cell, after years and years of solitary confinement’. The revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg gardened while in prison during World War One, while, alongside love letters and food parcels, seeds were collected and sent to Allied prisoners of war in German camps during World War Two. (For prisoners of war and internees during World War Two, according to Kenneth Helphand, ‘Gardens were a natural antidepressant and therapy for barbed-wire disease’. Sometimes the garden and liberation were even more directly connected: soil dug from Stalag escape tunnels was sprinkled by Allied prisoners on their vegetable plots for discrete disposal. Mulching to freedom?)

Addressing the Gardeners’ Benevolent Institution in 1852, Charles Dickens commented that ‘even the prisoner is found gardening in his lonely cell, after years and years of solitary confinement’. The revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg gardened while in prison during World War One, while, alongside love letters and food parcels, seeds were collected and sent to Allied prisoners of war in German camps during World War Two. (For prisoners of war and internees during World War Two, according to Kenneth Helphand, ‘Gardens were a natural antidepressant and therapy for barbed-wire disease’. Sometimes the garden and liberation were even more directly connected: soil dug from Stalag escape tunnels was sprinkled by Allied prisoners on their vegetable plots for discrete disposal. Mulching to freedom?)

More parochially, in recent years Chelsea Flower Show has featured award-winning show gardens by prisoners, so that the link between liberation or containment and gardening has never been far from the public imagination. What this sweep also suggests is a connection between the garden and the prison that constructs the garden as a space of escape, nurturing and liberation. While this can be a commonplace observation, in the restricted and routinised society of the prison it is a more compelling one—just as the everyday nature experience of fresh air or blue sky can be a more precious, snatched one for a prisoner.

The extreme garden of the prison is an inverted world: a walled garden of punishment rather than social privilege, with the primary function of the walls being to contain the gardener-convict rather than to protect the plants. Often walls are topped with barbed wire, ‘the iron strand that mocks and perverts the natural vines and thorns on which it is modelled’.

The extreme garden of the prison is an inverted world: a walled garden of punishment rather than social privilege, with the primary function of the walls being to contain the gardener-convict rather than to protect the plants. Often walls are topped with barbed wire, ‘the iron strand that mocks and perverts the natural vines and thorns on which it is modelled’.

Nelson Mandela worked a garden while incarcerated on Robben Island in South Africa for many years, and in 2005 wrote a book entitled Prisoner in the Garden. In his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom Mandela explains the attraction of the garden for the prisoner: ‘a garden was one of the few things in prison that one could control. To plant a seed, watch it grow, to tend it and then harvest it offered a simple but enduring satisfaction. The sense of being custodian of this small patch of earth offered a small taste of freedom’.

The appeal for prisoners is surely also one of the lengthy timescale involved in planting, the open-air, all-weather character of the garden, the potential for a temporary retreat into solitude, its reassuringly familiar domestic normality—and overall the tender tending of a fertile future.

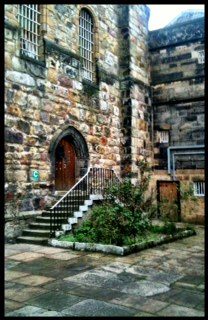

Today I joined a rare tour of Lancaster Castle, which until last year or so was a working prison, confining up to 400 category C prisoners (all for drugs-related offences). In the past its prisoners ranged from the Pendle Witches to the Birmingham Six. It’s an astonishing historic building, currently in a state of limbo as its future use is undecided—the massive ancient heart of a city that doesn’t quite have the money to rise to the building’s new challenge.

Today I joined a rare tour of Lancaster Castle, which until last year or so was a working prison, confining up to 400 category C prisoners (all for drugs-related offences). In the past its prisoners ranged from the Pendle Witches to the Birmingham Six. It’s an astonishing historic building, currently in a state of limbo as its future use is undecided—the massive ancient heart of a city that doesn’t quite have the money to rise to the building’s new challenge.

The oldest part of the castle, the Norman keep, formed C wing of the modern prison, and contained most recently a gym and an IT suite. What struck me is the (now unkempt) small rose garden, wonderfully placed by stone steps and an ancient ecclesiastical archway, edged by stone, in one of the oldest courtyards of the prison. Who had planted this, and who maintained it? I asked our guide, who seemed surprised by the question, and had no answer. A splash of green (and red roses, the county symbol of Lancashire, budding poorly now in neglect) in a bleak and sombre building of powerful, ancient, imposing stone.